Another toothsome morsel from McEwan

Ian McEwan's latest work seems to have all the ingredients that have madehis previous novels riveting reads.James Kidd takes the bait

Ian McEwan's 12th novel, Sweet Tooth, sometimes feels almost like a parody of a novel by Ian McEwan. Set in England at the start of the 1970s, the story is characteristically neither here (the multi-colour burst of the 1960s) nor there (the ravenous materialism of the 1980s). Here is a nation with no obvious identity, shovelled up by communist Russia, patronised by capitalist America, and found irritating by almost everyone else - in other words, an England ripe for McEwan's judicious insights.

Its genre too has no fixed abode. An obvious comparison is to John le Carre's gritty spy thrillers. But even le Carre's plots never unfolded as carefully and incrementally as this: imagine an audiobook of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold played at half speed. As with so much of McEwan's writing, the pleasure of reading Sweet Tooth comes from how his precise prose teases out social details, historical titbits and the mannerisms of a character.

It's like watching a forensic scientist looking for signs of life on a threadbare carpet.

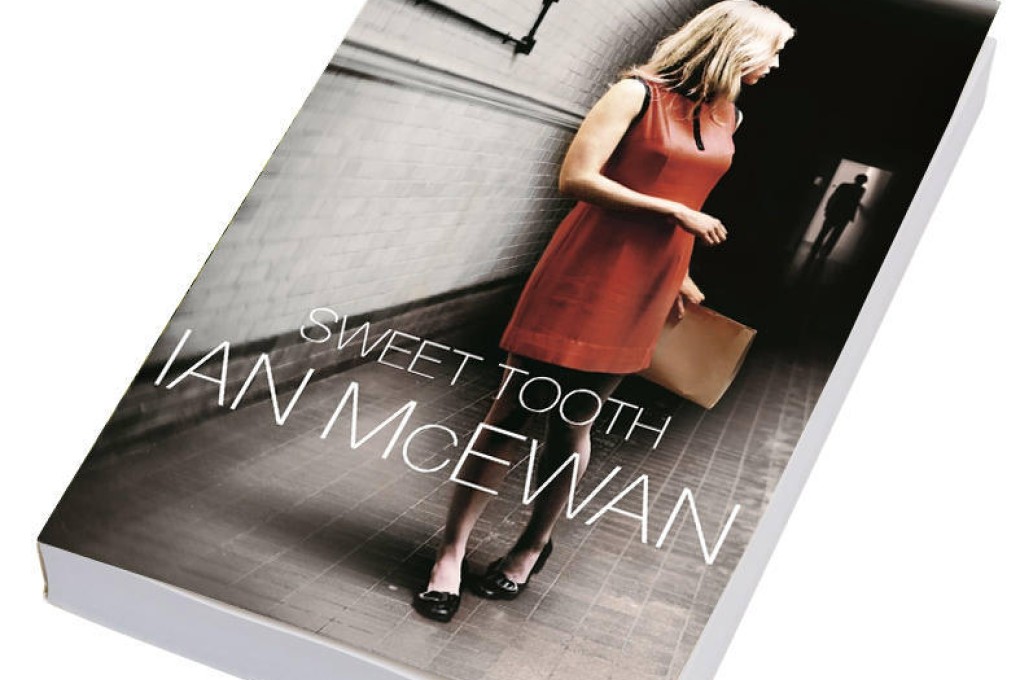

Here, for instance, is our heroine, the luminous Serena Frome, striding towards her destiny: Tom Haley, a young writer at one of Britain's then modern red-brick centres of higher education. Her mission, which Serena accepts because she works for MI6, is to win Haley's trust, fund his work in the guise of an arts organisation, and inspire what amounts to government-sanctioned propaganda. Haley, of course, will be none the wiser.

"The very word 'campus' seemed to me a frivolous import from the USA," Serena wonders. "For the first time in my life, I was proud of my Cambridge and Newnham connection. How could a serious university be new? And how could anyone resist me in my confection of red, white and black, intolerantly scissoring my way towards the porters' desk, where I intended to ask directions?"

And how could anyone resist such a measured, clear delineation of hushed, but guilty snobbery, effortless physical beauty and (via "scissoring") self-conscious urgency. You want to tell Haley: don't run with Serena Frome; you might just cut yourself. Then again, in this novel where certainty enjoys a mayfly existence, don't entirely trust even the smallest details.