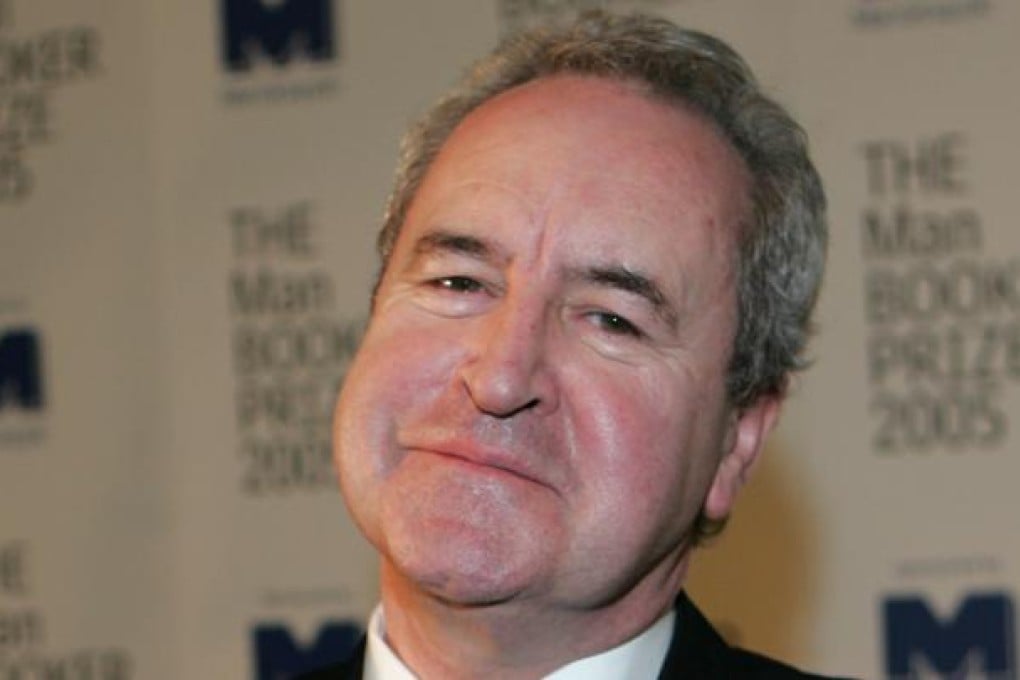

New John Banville novel plots the need to poeticise memory

Booker-prize-winning author John Banville explores the nature of memory or, as he would prefer to call it, imagination in his latest book.

In an interview, the Irish novelist said he intends for Ancient Light to stand alone, but those who have read his previous novels will recognise the character of Alex Cleave from Eclipse and Shroud, which explored other facets of his life.

This time out, Cleve, now a washed-up actor in his sixties, relives the affair he had with a friend’s mother at age 15 in their small Irish town.

Cleave’s present life finds him developing a bond with a troubled young actress that drives him toward making peace with his daughter’s suicide, but his vivid recollection of his illicit first love is the larger plot.

The novel, recently published in the United States, was described as “an unsettling and beautiful work” by the Wall Street Journal. The Daily Beast likened its sensuously detailed recollections to the work of Proust.

As Cleave richly narrates his adolescent erotic awakening by the 35-year-old Mrs Gray, hesitations about the accuracy of those memories and their missing fragments interrupt.