Read the winning entry in the RTHK-SCMP short story competition

'Ah Choy' by Irene Tsang is a worthy winner of this year's RTHK-SCMP Short Story Competition

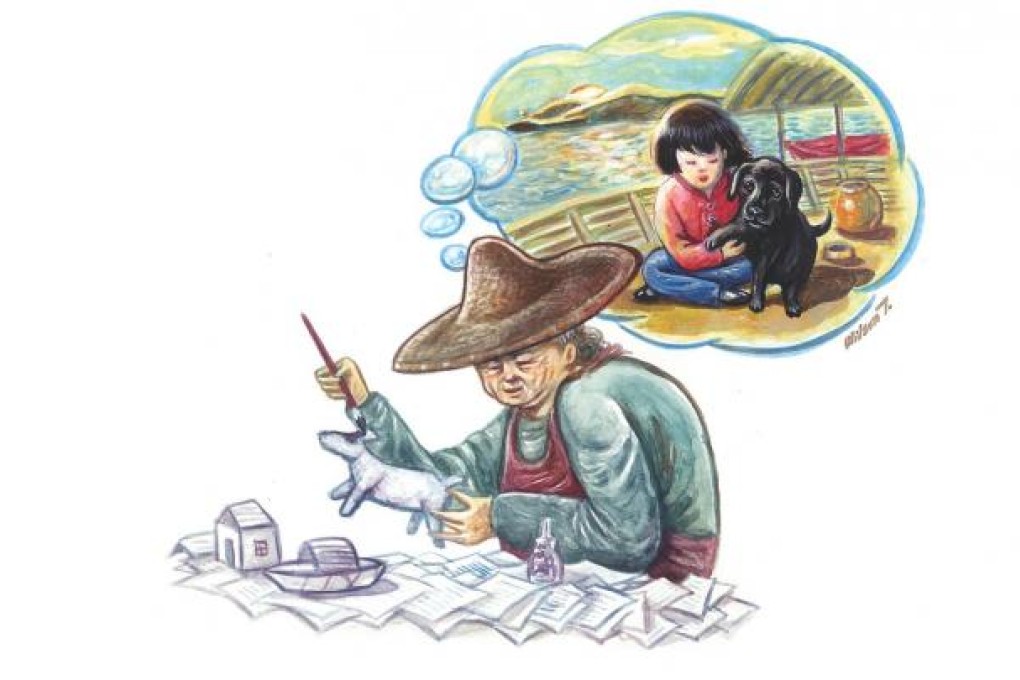

It's been too long since someone called me by my name; I'm beginning to forget what it is. Instead, I answer to Lapsup por, the trash hag. Really it's not as bad as it might sound. People smile and say " Jo san Lapsup por", their morning greetings familiar and friendly. They don't ever get me mixed up with other old women. I'm known for a name, for picking up what everyone throws out and that makes me a useful person. I sort out the good trash from the bad: cardboard, paper, glass and cans, these are good trash; wilted vegetables, orange peels and fish bones are bad. I clean all 12 floors of this building on Hong Lee Road. The other day I even found a pair of really nice shoes, pretty green stripes on white canvas, in the sixth-floor bin. I washed them and they are good as new and now I wear them every day.

People like us have bent backs; some older ones are more bent than me from all the stooping. Sometimes my back hurts but not too much, because the pain means you can work and that is good.

Most everybody thinks we are poor, and in my case it's true. It's always been true. I never have much money but I have food and a place to live, so there are worse, much worse. I collect $3,480 from the building I clean and the government also gives me fruit money every month. I know I can sell paper for more money; other old women do that but I've never gathered enough to make it worth the trip to the collector. Also I don't want to upset others; they do the paper and I pick up other trash. I'm quite happy with the odds and ends that I can sell. But on the 10th floor, every Friday they throw out a stack of paper, I think because someone who lives there also works there. Smooth white pages with words on one side that mean nothing to me. This I take.

I was born some time in the spring when people still lived on fishing boats. My parents and their parents were Tanka and we lived most of our lives in Sam Ka Chuen, a crowded village then. I heard now it's a fancy place for tourists to eat shrimp, grouper and lobsters, but in the old days, when we were nine in our boat, it smelled of sweat, unwashed skin and human waste in murky water. From this paper, I mould the shapes of boats, people, houses and everything. It's like I never left.

One cold night when I was six, some men brought a few puppies back to the village, and our neighbour told us they were going to eat them, so a bunch of us kids ran to that house to watch. The puppies were playing in the front, each with a rope tied around its neck.

The fat man with no front teeth patted one of the puppies. "Ahh, this black one is good. Its meat is guaranteed to boost your strength."