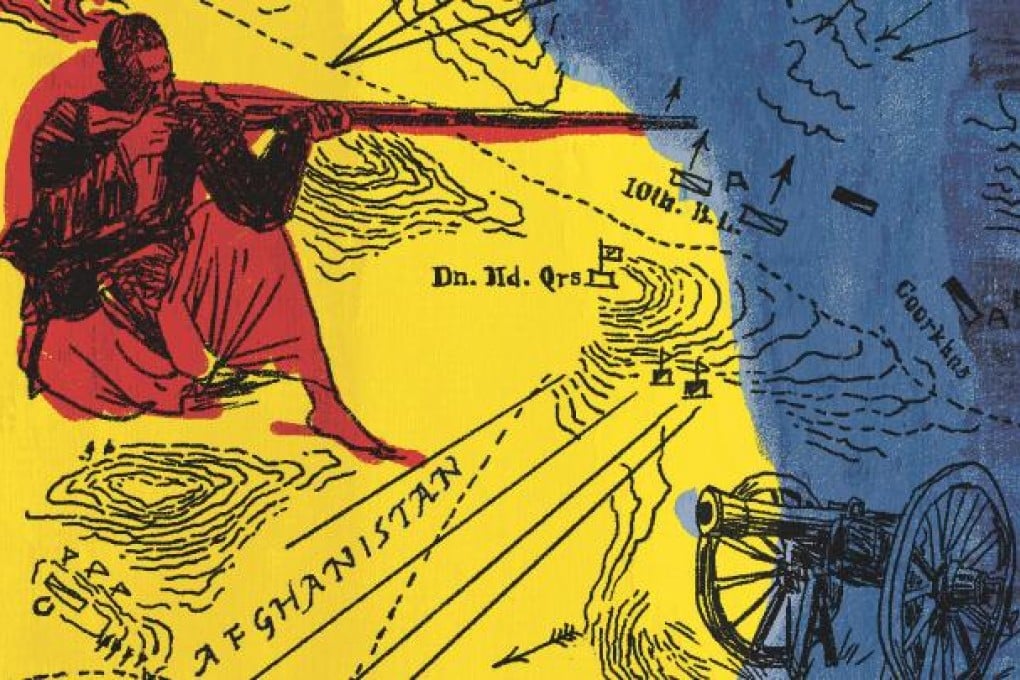

Afghanistan: the great game of thrones

Historian William Dalrymple's new book charts the disastrous British attempt to set up a puppet king in Afghanistan in 1839, writes Manreet Sodhi Someshwar

Return of a King

by William Dalrymple

Bloomsbury

Britain had conquered most of India by 1939, but its empire was stalled at Punjab by the powerful Sikh king Ranjeet Singh. Russia, the other big empire of the time, was moving south through Central Asia.

What stood between these two empires was the fractious, mountainous region of Afghanistan, for centuries the gateway to Hindustan for invaders. But what if Russia decided to follow in the hooves of those conquerors? Eager to secure its prized treasure of India, Britain decided to pre-empt the Russians by invading Afghanistan.

Thus began the Great Game, a term coined by Sir Henry Creswick Rawlinson, an Englishman who first sighted Cossacks in the disputed borderlands between Persia (today's Iran) and Afghanistan in 1837 and alerted his superiors. "As so often in international affairs, hawkish paranoia about distant threats can create the very monster that is most feared," writes William Dalrymple in Return of a King, a chronicle of the first Anglo-Afghan war from the spring of 1839 when the invasion began to the autumn of 1842 when the Union flag was lowered.

The deposed Afghan king, Shah Shuja, had earlier sought British protection and had been living in Ludhiana, Punjab. The British decided to reinstate him on the throne and manage the country through this puppet. There was a second opinion to back the incumbent ruler and gain Afghanistan without bloodshed. However, the administration was rife with internal politics and nepotism, which resulted in twin policy tracks that were hostile to one another. The shah's backers won eventually and amassed an "army of the Indus" to defeat the incumbent ruler, Dost Mohammed Khan. It was made up of 58,000 men and 30,000 camels, and with Ranjeet Singh's assistance, was able to take Kabul and install the shah.