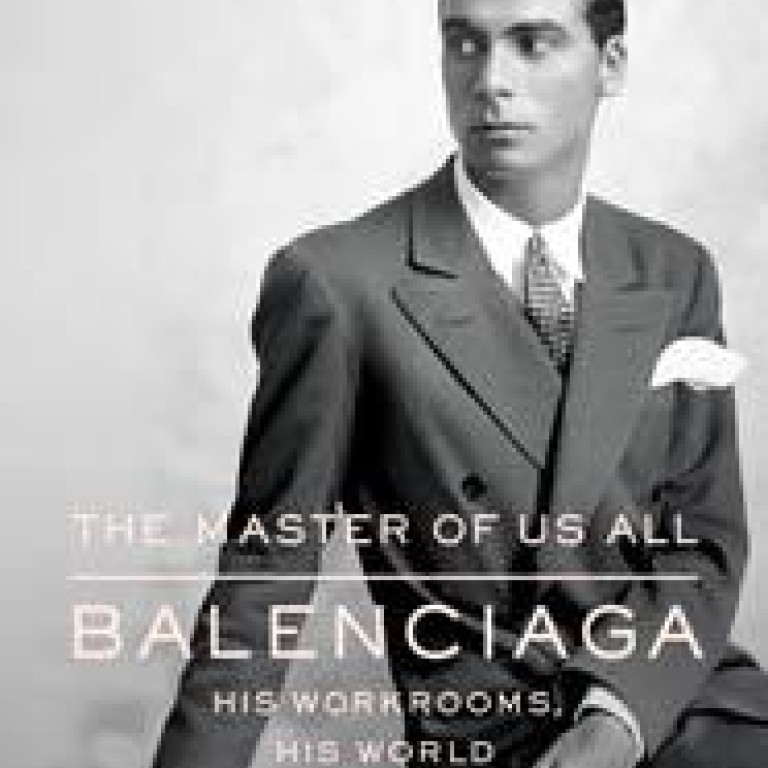

Book review: The Master of Us All, by Mary Blume

Paris-based journalist Mary Blume knows that many in the current generation associate Balenciaga not with the artful, painstaking couture of the master, but with the ready-to-wear line, sneakers, bags and burgeoning boutiques of the designer's recent successor, Nicolas Ghesquiere. Would Balenciaga have approved of this approach?

by Mary Blume

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Paris-based journalist Mary Blume knows that many in the current generation associate Balenciaga not with the artful, painstaking couture of the master, but with the ready-to-wear line, sneakers, bags and burgeoning boutiques of the designer's recent successor, Nicolas Ghesquiere. Would Balenciaga have approved of this approach?

In her penetrating and entertaining new biography, Blume acknowledges that even in his heyday, Cristobal Balenciaga was something of a cipher.

Born in a Basque village in 1895 to a fisherman father (who soon died) and a seamstress mother, he was sewing clothes for the Spanish nobility in his teens, established half a dozen Spanish fashion houses in his 20s and 30s, and in 1936 opened La Maison Balenciaga in Paris on the Avenue George V.

Intensely private, he shunned press and publicity, which meant that the inner workings of his private and professional life remained largely unknown, apart from such facts as that he loved skiing and had bad sinuses.

Nonetheless, in her youth, Blume had a brush with one of Balenciaga's most trusted employees, the vendeuse (saleswoman) Florette Chelot, which has allowed her to expand the stock of colourful lore about the designer. In a series of recorded luncheons, which continued until Chelot died in 2006 at the age of 95, the vendeuse shared her trove of memories with the author, supplying her with bushels of rustling anecdotes to applique onto Balenciaga's curiously seamless life.

In the 1960s, when Blume arrived in Paris, a friend took her to the flagship and introduced her to Chelot, who was "svelte in her black Balenciaga, her hair tight in its tidy chignon". Struck by the "voluptuous austerity" of the house and the nunlike ranks of stern black-clad vendeuses, Blume regretted her simple shirtdress. Chelot "rummaged around" and found a blue light wool tailleur she could afford. Fifty years on, the author remembers this suit, which, like "all" of Balenciaga's creations, lent a quality of "poise - a savant equilibrium" to the woman who wore it.

Ten years later, Balenciaga was dead - and with him, arguably, the age of haute couture. The arrival of the jet set spelled the departure of the Cunard set. As air travel and lightweight luggage replaced ocean voyages and steamer trunks, society women lost interest in couture dresses and the girdles and fittings they required. By the time Diana Vreeland's Balenciaga retrospective opened at the Met in March of 1973, the designer already seemed to belong to nostalgia's attic.