Pitfalls in immigrant writer's road to becoming American

Born in Shanghai in 1957, Anchee Min was taught to write "long live Chairman Mao" before she could write her own name.

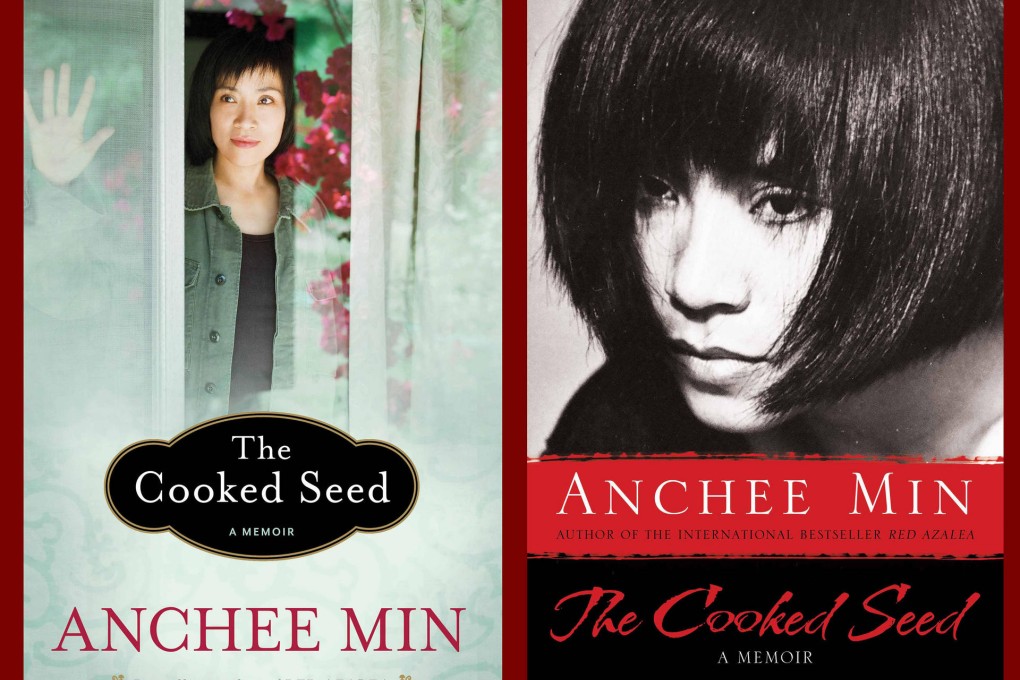

Born in Shanghai in 1957, Anchee Min was taught to write "long live Chairman Mao" before she could write her own name. Sent to a labour camp in East China at 17, Min endured three years of hardship before a talent scout from Mao Zedong's wife Jiang Qing's Shanghai Film Studios recruited her as an actress because of her ideal "proletarian" features. But when Madame Mao was sentenced to death soon after, Min was disgraced as a political outcast. Forced to perform menial tasks to reform herself, she left China for America in 1984 where she wrote her memoir about those years, Red Azalea . Praised for its raw, honest prose and historical accuracy, Red Azalea was praised by The New York Times in 1994 and sold in 20 countries. Since then, she has penned six internationally acclaimed historical novels about China, including Katherine , Becoming Madame Mao , The Last Empress and, most recently, Pearl of China . Now, two decades after Red Azalea , comes her follow-up memoir, The Cooked Seed. Min talks to .

There are a lot of elements. After all these years working as a writer, I felt there was an angle that had never been explored because most of the Chinese people who come here to America have already achieved a college degree. But I came here without any English and so really mixed with America's poor and working class. I also wanted to write it for my daughter, Lauryann. I found the challenge was that she doesn't really know me, because I had never told her, those things that I think most Chinese women never tell, those terrible, awful, intimate memories. As an immigrant you tend to glorify things and as a Chinese woman I'm expected to stay silent about whatever embarrassing things have happened to me, even my divorce. But I feared that my daughter would end up like me. I never knew my mother and my mother never got to know me.

It's the primitive thoughts, desires and emotions - the truth. I felt like until I could face myself, give a mirror-image description, I didn't think I was doing my job. There are some chapters that, in The Cooked Seed, I almost deleted immediately after I'd written them because I thought it was humiliating, embarrassing and shameful to share them with anybody. Yet I felt that without them, I couldn't convey, for example, the degree of an immigrant's crushing loneliness, the cruelty, the depravation of the human animal's basic needs.