Migrants' flawed champion

Migrant to 19th-century US fought for the rights of his fellow Chinese, writes Vanessa Ko

Wong Chin Foo did not manage to hold on to his celebrity posthumously: most Chinese Americans would not recognise his name today.

There was no wasted opportunity to draw attention to his causes. Wong started out dressing up in Chinese regalia to help Americans understand Chinese culture, and ended with soaring oration in his passionate fight for equality as he pushed for the US government to overturn a law that made it illegal for Chinese, and Chinese alone, to become naturalised citizens.

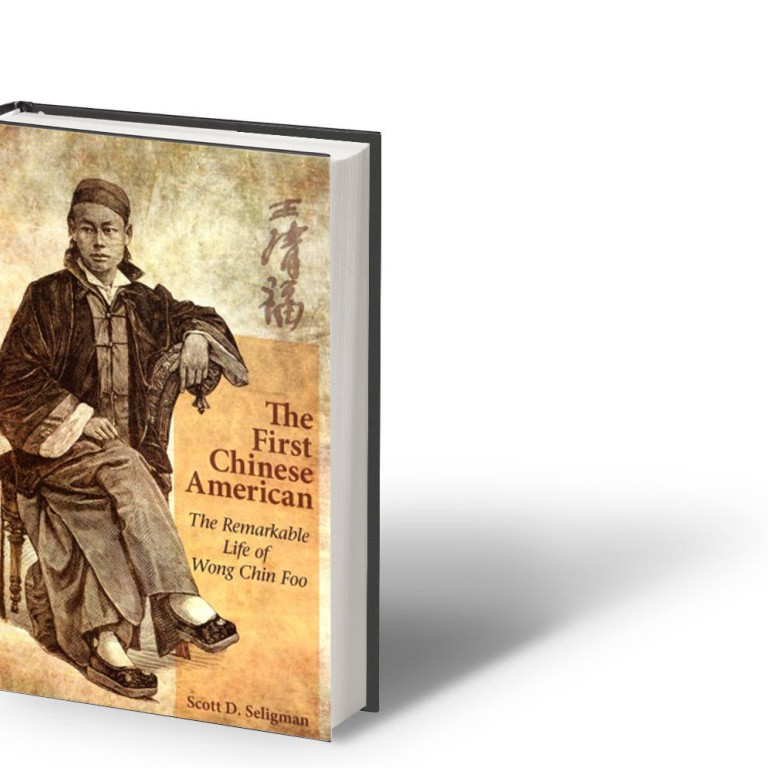

Wong was no saint and in , biographer Scott D. Seligman paints him as someone who was unreliable, a brash man who made both Chinese and white enemies easily, an egoist who often contradicted himself.

From the time he was sent by US missionaries from Shandong province to American soil in 1867, when he was 20 years old, until his death 31 years later, Wong survived several assassination attempts in Chinatown, precipitated by his interference in illegal activity and money issues between laundrymen.

He was sued repeatedly, arrested a few times and had a litigious streak, too. He irrationally hated and denounced the Cantonese, calling them "low life" - although his friendly relationship with Sun Yat-sen was an exception.

To further his agendas, often to defame his enemies, he started at least five Chinese newspapers, none of which lasted long. His first publication was called , and it is the first recorded usage of the term.

Wong was not literally the first Chinese American. Tens of thousands had crossed the Pacific to the US before him, and a handful had become citizens before his naturalisation (most Chinese were not interested in becoming citizens but planned to return to China after making their fortunes). But he was the first to vocally champion the Chinese presence in the country and drew plenty of attention doing so.

Is it then a crime to be a Chinaman? Shall I be dragged from my bed at midnight because I shall refuse to be photographed?

To understand Wong's life, it was essential for Seligman to trace the history of Chinese immigration to the US, which he interweaves into the biography. When the Chinese first started migrating to the US during the California gold rush of the mid-1800s, they were not yet viewed with hostility by Americans. But by the 1870s, the Chinese were seen as a threat to the US workforce with their low-cost labour, and the government in 1882 imposed the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring further entry by Chinese, while those already residing in the US were no longer permitted to become citizens. But when the Chinese continued to enter illegally, a separate law followed: the Geary Act required the Chinese to register with the government, provide at least one white witness of their residency there before the exclusion passed, be photographed and carry identification papers at all times.

In his fight to have the Geary Act repealed, Wong appeared before Congress, probably the first Chinese to ever do so. His speech was the high point of his career as an orator: "Is it then a crime to be a Chinaman? Shall I be dragged from my bed at midnight because I shall refuse to be photographed? No, I will not be photographed against my will like a criminal. I would be hanged first. Why should we be made the subjects of discrimination, of indignity, of animadversion and proscription?"

The photograph requirement was cancelled, and Wong's passionate appeal to Congress was thought to be responsible. Still, despite his efforts, the Chinese Exclusion Act would persist for decades after Wong's death.

Wong tried to support the Chinese presence and image through other causes, too. And although he was adopted by Christian missionaries in China, baptised and sent to the US by them to further his education, he quickly came to reject Christianity. He travelled around North America giving lectures on Buddhism and Confucianism, spreading knowledge about these Chinese traditions and showing how the tenets are similar to those of Christianity.

In the talks he gave, he articulated that he respected Christianity and had no problems with most missionaries or their activities, but he objected to "their slandering and vilifying the intelligent classes of China by representing them to be a degraded and idolatrous people", according to .

He also famously penned an essay titled which was much more critical of Christianity. But most pointedly, he blamed missionary work for the vast quantities of opium brought into China in his powerful rhetoric: "And on you, Christians, and on your greed of gold, we lay the burden of the crime resulting; of tens of millions of honest, useful men and women sent thereby to premature death after a short miserable life, besides the physical and moral prostration it entails even where it does not prematurely kill! And this great national curse was thrust on us at the points of Christian bayonets. And you wonder why we are heathen?"

One of his most ostentatious plans to draw attention to himself and his causes was the establishment of a Confucian temple in Chicago, to which he appointed himself high priest. As with most things Wong started however, it did not last; the temple was closed after the first sermon.

The gesture was typical Wong: an orator putting on a show, if only for his audience to listen.