Some hope in a hell of an ending

Margaret Atwood's post-apocalyptic trilogy concludes with a rumination on mortality, continuity and the vital role of stortytelling

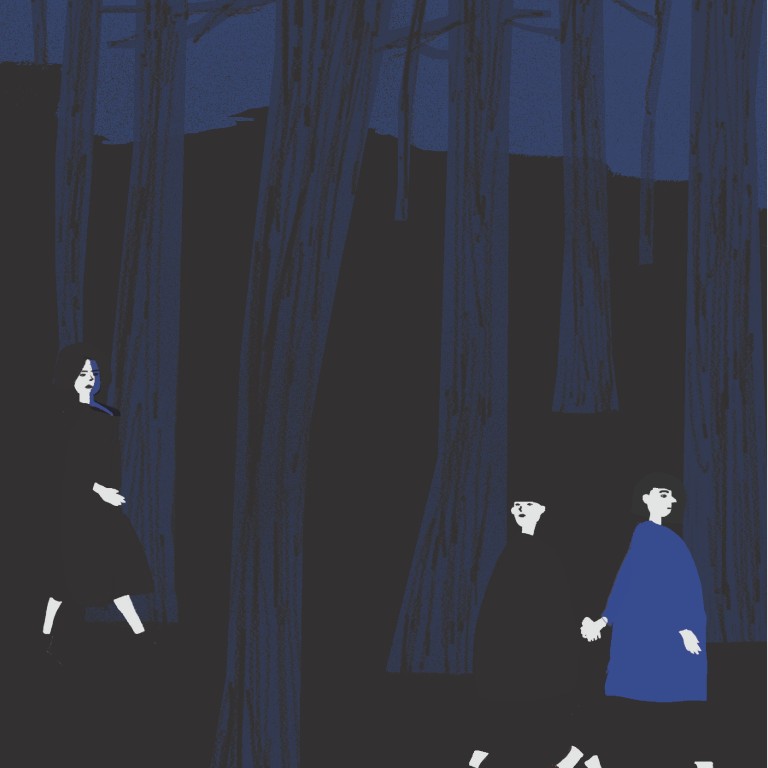

When posterity reviews the art produced in the early years of the 21st century, it will be hard to miss the number of dystopian narratives proclaiming that it's the end of the world as we know it. Whether you enjoy popular entertainment such as or more literary fare like Cormac McCarthy's , the apocalypse is never far away. And if a plague, ice cap or stock market crash doesn't get you, then the zombies surely will.

, Margaret Atwood's 22nd novel, both participates in this noble tradition and pre-empts its modern resurgence. For one thing, it is the third part of a trilogy that began in 2003 with , and continued six years later with . Being smarter than the average novelist, Atwood knows her place in the scheme of things and plays along accordingly: "Speculations about what the world would be like after human control of it ended had been - long ago, briefly - a queasy form of popular entertainment."

Atwood has faith in the future of mankind, no matter how desperate the present

Atwood has never been one to ignore the claims of popular entertainment, however queasy. At the same time, this is a writer whose career - fiction, poetry, non-fiction or children's stories - deserves to stand alongside any writer of the past half century. Read together, Atwood's triptych comprises a brightly coloured 21st-century epic. Only, doesn't "sing of arms and a man", but of arms, a man, a woman, a small community of humans (Snowman-the-Jimmy), Amanda, Ren), vast herds of genetically created pigs, a race of innocent humanoids bred in a laboratory, and a band of renegade psychopaths hoping to defile all of the above.

The plot is rudimentary, but in its final stages tense and exciting. A band of rag-tag survivors have outlasted a global pandemic sent to cleanse the planet of mankind once and for all. Atwood's misfits forage, cook, bicker, reminisce about decent coffee, have sex, hold secret crushes, and try desperately not to die. There are many ways this can be accomplished. There are monster Pigoons (part Homer, part Orwell) who rage whenever one of their number ends up in a bacon sandwich. Even worse are the "Painballers": rogue psychopaths who have found superstardom through a sport that makes look like Crown Green Bowling.

After an entente cordiale with the hogs, the tribe declares war on the Painballers. The final conflict takes place, with ironic symmetry, at the Egg, the laboratory in which the Crakes were conceived. Atwood's characters come full circle, but whereas book one was concerned with birth and re-birth, has a death-soaked sense of an ending.

Anyone whose memory of is either foggy or even non-existent need not despair. Atwood opens with a handy recap that parodies long-running TV series ("The story so far") and the chapter summaries of 18th-century fiction: "The story of the Egg, and of Oryx and Crake, and how they made People and Animals …" This précis does more than make accessible to readers unaware of . It introduces Atwood's diverse modes of narration. 's action and characters are presented and re-presented in a series of self-consciously dramatised storytelling sessions - with a teller and an audience - that marry the directness of oral traditions to Atwood's characteristically robust prose.

both completes the series, and remixes its opening episodes, which is apt as motifs of storytelling, splicing, origins and endings run throughout Atwood's new work. The longest sections are told by our hero, Zeb, to our heroine, Toby. These accounts of his life and adventures become a kind of love story. Not that Zeb's subject is romance: he's keener on sex, his cult-leading father, his brother Adam, and his life as a computer hacker. Instead, these intimate acts of confession and revelation help bring Zed and Toby together after years spent flirting too subtly for their own good.

At the end of each day, Toby recycles these tales, and others, for the Crakes. Her bedtime stories are part ritual (she must wear a battered Red Sox baseball cap, a broken wristwatch and eat a fish) and part myth creation: a way to make a chaotic, violent and capricious world seem comprehensible for the gentle, child-like Crakes.

Told in simple prose, these sections are moving, but also very funny. Atwood is not always praised as a comic writer, but reveals a fondness for bad puns (Occam's razor becomes "Ock-ham" during a swinish encounter), offbeat one-liners ("I once had a conversation with my bra") and some inventive running gags. When Snowman-the-Jimmy yells "f***" in front of the baffled Crakes, an embarrassed Toby turns the curse word into an abstract being, who is then absorbed into the Crake religion as a demi-god: "Oryx will be helping me," says a Crake called Blackbeard. "And F***. I have already called F***. He is flying to here, right now, you will see."

One senses Atwood pondering the joys and burdens of her craft. While Toby is often inspired when explaining human folly, good and evil to the Crakes, she frets about the truth of her yarn spinning. Do her consoling myths explain life and death to the Crakes or mislead them about its grimmer reality? "She doesn't like to tell lies, not deliberately," Toby says of her nightly contrivances, "not lies as such, but she skirts the darker and more tangled corners of reality." When Blackbeard finds his creators' skeletons, he howls: "Oryx and Crake must be beautiful! Like the stories! They cannot be a smelly bone!"

There are even moments when Toby tires of the demands of her rabid audience. "It's evening. Toby has dodged her storytime session with the Crakers. Those stories take a lot out of her. Not only does she have to put on the absurd red hat and eat the ritual fish … but there's so much she needs to invent."

If Atwood is similarly weary, it doesn't show in her prose, which soars with the immediacy of improvised narration. is not a tragedy, or a depressing read. Atwood has faith in the future of mankind, no matter how desperate the present. The novel ends with the possibility of regeneration: "The Swift Fox told us that she was pregnant again and soon there would be another baby … And Swift Fox said that if it was a baby girl it would be named Toby. And that is a thing of hope."

This vitality seems acutely alert to its opposites - to finality and death, whether of her trilogy, her characters, the planet and, one suspects, Atwood's own mortality. "Is this what writing amounts to? The voice your own ghost would have, if it had a voice?" Toby asks at one point. Is Atwood surveying her legacy, literary and otherwise, out of the corner of her eye?

Dedicated to her family, is an extraordinary achievement. The sort of loose, baggy novel at which Atwood has thrown everything except the kitchen sink (there are no kitchens or sinks in Toby's world). It ends with a bravura meditation on the power, consolations and endurance of literature itself: "And I have done this so we will all know of her," Blackbeard writes of Toby, "and of how we came to be." Atwood's body of work will last precisely because she has told us about ourselves. It is not always a pretty picture, but it is true for all that.