Novelist finds another medium of expression in ink and canvas

Madeline Gressel is captivated by a collection of writer Gao Xingjian's poignant ink works

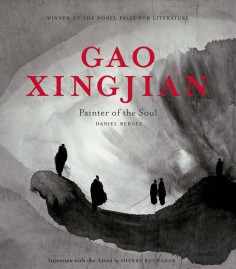

Gao Xingjian: Painter of the Soul

by Daniel Bergez

Asia Ink

4 stars

In 2000, Chinese-born artist and émigré Gao Xingjian won fame and a Nobel Prize for Literature for his experimental novel, , loosely based on his travels in western China and his oppression at the hands of the mainland authorities.

The prize earned him international recognition for his work as a novelist and playwright, but his equally accomplished ink paintings are less known. Now, local publisher Asia Ink has collected more than two decades' worth of Gao's extensive work in a beautiful grey-scale tome, alongside lengthy commentary by French art critic Daniel Bergez.

His works (always black ink on paper and, later, canvas) blend the abstract and the literal in remarkable, decisive ways

Born in 1940, Gao was a child of the Cultural Revolution. Like millions, he was "sent down" for re-education to the countryside of Anhui province in 1962. He worked for years as a French translator, and even though he had been writing and painting prolifically since childhood, it was only in 1979 that he wrote professionally, as an official party playwright. He gained a reputation for his absurdist drama. Then, in 1985, an exhibition of his ink paintings was shown at the People's Art Theatre in Beijing.

Gao fled the mainland in 1987 in an act of self-imposed exile following a misdiagnosis of cancer and rumours of his imminent arrest. Since then, he has been both lauded and criticised internationally for the complicated, elusive and labyrinthine structure of , which eschews a traditional plot for a series of personal, evocative ruminations. The narration is split four ways - between I, You, He and sometimes She - in a contemplative nod to postmodern epistemologies.

Figures lead the eye to other figures. The beauty of the image lies in its mutability. "[The paintings'] creative legitimacy," Bergez writes, "is not drawn from mimesis but from the attention they demand as creations in themselves. The only 'subject' of these paintings appears, at first sight, to be light, how it travels, its source and fragments, played out over and over again in dialogue between black, white, and varying shades of grey."

Collected, the images are nothing short of astonishing. They are featured in chronological order, but, like in , the effect is more cyclical than linear, returning again and again to variations on emotive themes.

Of course, Gao is a master of his craft. His knowledge of variation in ink hue and paper texture seems inexhaustible. His paintings achieve a rich, abundant quality that is remarkable, considering the relative flatness of ink compared to the thick, tactile layering of an oil painting. Some images, such as , resemble the grey-scale paintings of his European contemporary Gerhard Richter: photographic realism, tampered and slurred.

Unfortunately, Bergez's text does not mirror the lovely impressionistic simplicity of the images it attempts to illuminate. He declares: "[Gao's paintings] defy language that uses compartmentalised and hierarchical notions and reconstructed systems to represent the world. To give a verbal equivalence to his paintings would reduce them to a 'message' or a 'theme', removing their radical otherness, which is their very nature for their reason to exist." This, followed by thousands of interpretive words, including an examination of Gao's "Grammar of Shapes" under the heading, "Interrogating the Works". Bergez wants to have his cake and blab about it too.

His language is that of the academic hagiographer - this interpretation is "problematic", that one "projecting" - who jealously guards the keys to comprehension. He stands ready to tell us in exactly what proportions Gao's work is figurative or abstract, Western or Chinese, and for the reader, this quickly becomes tiresome and didactic.

At times, it all feels a bit like myth-making: Gao's studio is unlike any other artist's, he refuses to make preparatory sketches, and so on. Bergez lauds Gao's withdrawal from the media and his "refusal to be indoctrinated by existing systems of thought … the price of course is solitude". He compares Gao's brushstrokes to that of the Creator, the deus pictor. And that's not all. It's sexual union! It's love! It's hand-to-hand combat!

Bergez seems bent on convincing us that Gao is an absolute original. But Gao's genius does not arise from his revolutionary qualities as much as from his incredible technical ability with a brush and his intuitive understanding of natural beauty.

Some of the most interesting interpretation happens when Bergez sinks his teeth into Gao's aesthetic and philosophical connections to Taoism. He quotes Gao as saying, "I am neither Taoist nor Buddhist, and what I adopt is simply an attitude of observation". Still, the correlation is undeniable. Like Taoism, Gao's works are a never-ending conversation between light and dark, yin and yang.

In Gao's paintings, the negative space is never empty, never silent, but active, speaking. In , an ovoid white space at the centre, unpainted, seems to coalesce above the page. Conversely, in the flatness and sparseness of his many blacks, there is always the elusive suggestion of infinity.

As Bergez says: "Each work is a cosmogony in miniature."

Though Bergez claims much of what is meaningful in ancient Chinese ink painting, the art of the literati, is present in Gao's work, his discussion of modern influences is almost exclusively limited to Impressionists and Expressionists: Manet, Picasso, Soulages. He even refers to Marcel Proust but, curiously, not once to a contemporary of Gao's.

Still, Gao's work is saturated with a sense of longing and nostalgia for a forsaken homeland. Especially in his later work, images of a lone figure on life's journey, a terrifying metaphysical quest, abound. As in , Gao evokes the sense of a mythical homeland, both real and dreamed, and always just out of reach.

At times, the language in comes reasonably close to approximating Gao's images - though they are not literally linked. "If you go on you will come to an abyss, I say to myself," he writes. "A belt of weak light, like a fence among the trees, appears briefly then vanishes. I discover that I am already in the forest on the left of the road; the road should be on my right."

If language offers only a pale imitation of the boundless beauty of Gao's art, so too are these photographs imperfect reflections. Nevertheless, lacking the original works, they are the most beautiful of replicas.