Book review: Yu Hua's The Seventh Day - grim satire on China's poor

In his latest novel, the Chinese author shows that, in death as in life, there's neither justice nor equality

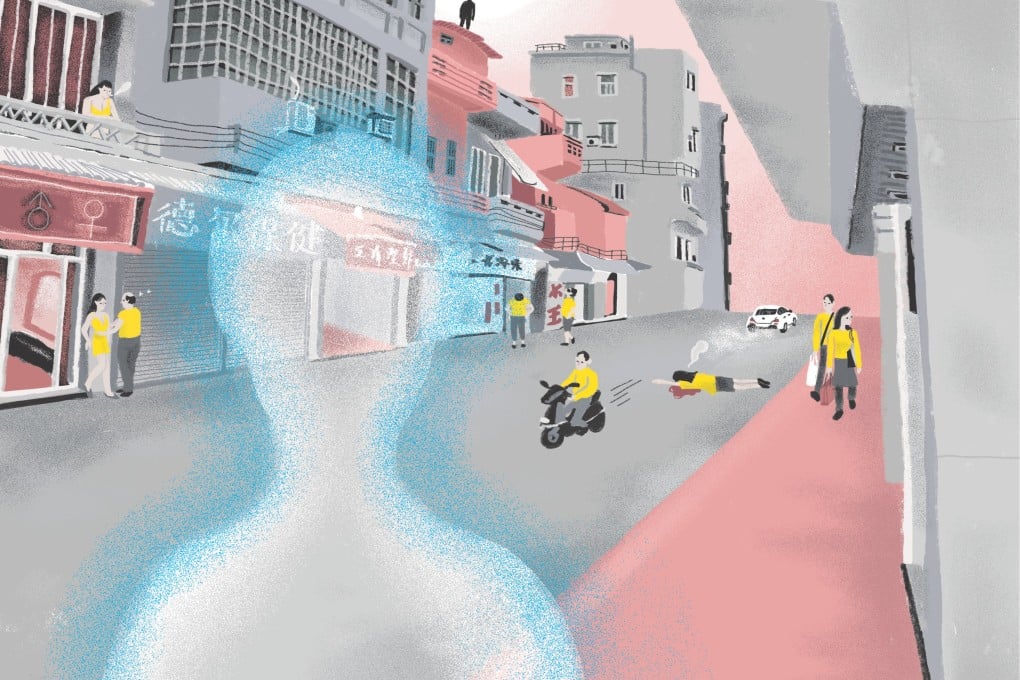

In The Seventh Day we meet narrator Yang Fei in the land of the dead. Yang is a 41-year-old Mr Average: a man with no children, little money and few prospects. He leaves his bedsit and walks aimlessly "in the barren and murky city". It is the first day of his death. But with no one to bury him, and no one to mourn him, he is consigned to a restless state roaming among the spirits of the fallen.

During Yang's seven days of wandering, he meets the other people in his life who have also died and, like him, can find no peace. There's his ex-wife, a beautiful and ambitious businesswoman who slit her wrists following a corruption scandal, to the down-to-earth family who ran the local noodle restaurant. Along with Yang, they perished in a gas explosion in the kitchen.

Yu Hua uses this conceit - at times both playful and unsettling - to explore the chaos of modern China. In the process he upturns all that is wrong in a country where lust for money and power has upended common decency. But while The Seventh Day is desperately dark, it is also darkly funny.

This is best illustrated in the opening chapters in which Yang checks into the cremation clinic, having made makeshift burial clothes for himself out of old pyjamas. In the waiting room, the dead tarry for their turn. Yang is given a number and told to bide his time. But even in death not all are equal. Yang has no resting place: he is in a Chinese version of purgatory. Others, the lucky, have family who can scrape together enough cash to bury them.

Meanwhile, the wealthy have made arrangements for extravagant burials designed to both guarantee luck in the afterlife and save face in the world they leave behind. As one of the soon-to-be-cremated moans: "Dying is such an expensive business these days!"