Book review: analysing Don Quixote, the dynamo at the heart of Spanish culture

In the four centuries since it was published, Cervantes' novel has become a timeless classic of world literature, speaking afresh to each new generation

Not only does Miguel de Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote tower over Spanish literature like a giant windmill, it also can be seen as a turbine that powers Spanish culture. But the novel’s kinetic energy extends beyond the Iberian peninsula. As scholar Ilan Stavans catalogues in this engaging cultural history, Don Q and Sancho Panza have a powerful, ongoing influence on Latin American and US literature and culture as well. Except for the Bible, no book has been translated into English more often, Stavans declares, listing 20 different English translations between 1612 and 2009.

Stavans, a professor of Latin American and Latino culture at Amherst College in Massachusetts, walks around the novel as if it were one of the famed sculptures of Don Q in a Spanish plaza, finding something notable or surprising to discuss from every angle.

With its digressions and interpolated tales, the baggy Don Quixote is far from an example of what Flaubert called le mot juste – though, Stavans points out, the author of Madame Bovary adored El Quijote (the Spanish honorific that pays homage to the novel’s primacy).

Don Quixote’s stature as the first modern novel comes from its consuming interest in fantasy (or idealism, or madness) versus reality, its bookishness (too much reading, after all, launched the knight-errant on his errant career), and its playful self-referentiality (such as the scene in which the barber and the priest, deciding which books from Alonso Quijano’s library to burn, consider the merits of an author named Cervantes).

Of course, the knight and his squire have influenced or inspired countless odd-couple and mismatched-buddy stories.

“No same-sex literary pair has ever been as famous, as emulated, or as quoted as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza,” Stavans declares.

His list of descendant couples includes Watson and Holmes, Abbott and Costello, Laurel and Hardy, Frodo and Sam Gamgee, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Didi and Gogo (of Waiting for Godot), even Batman and Robin. You may not see eye to eye with Stavans on some of these, but there’s no arguing with the notion that Cervantes laid down a template that still yields fruitful variations today. (If Professor Stavans were an alt-rock guy, he might also have mentioned another dynamic duo – the band They Might Be Giants, who draw their name from the novel.)

“Cervantes’ most lasting contribution is the depth and complexity of his language,” he writes. While he doesn’t credit Cervantes with the volume of coinages attributed to his English contemporary, Shakespeare, Stavans notes that “Cervantes’ syntax has become the default standard style in Spanish”.

In the second half of his book, Stavans explores the concept of Quijotismo, which he describes as the Spanish and Latin American counterpart to US exceptionalism and the American Dream. To explain it, he paraphrases Montaigne: to sacrifice one’s life for a dream is to know its true worth.

He sees Quijotismo in Unamuno’s essays, Goya’s paintings – even Subcomandante Marcos’ rebel movement.

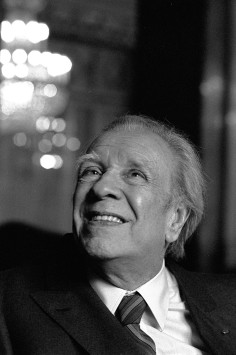

From the many Latin American descendants of and responses to El Quijote, Stavans singles out Jorge Luis Borges’ audacious story, Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote (1939), a purported essay-review of a French Symbolist’s efforts to rewrite, but not copy, Don Quixote word for word.

In a mind-blowing segment, the story’s narrator compares a short, identically worded passage from both Cervantes’ and Menard’s Quixote, finding them completely different in effect. Borges’ story, Stavans explains lucidly, is an argument for reading itself as a creative act, as well as an assertion that the former Spanish colonies can acknowledge a cultural debt to the motherland while nonetheless finding their own way.

Stavans explores film (including Orson Welles’ abortive attempt), ballet and stage adaptations of Don Quixote, finding most of them wanting, if not outright disasters.

As for The Impossible Dream from Man of La Mancha, Stavans declares that it “sticks like chewing gum. There is something innately American in this mantra: the self is at the core of all adventures, and each of us needs to protect our own self, make it flourish.”

Quixote: The Novel and the World by Ilan Stavans (Norton)

Tribune News Service