Salman Rushdie on his new novel, the Indian and Arab tales that inspired it, and the constant battle against fundamentalism

Worn out by writing his memoirs, Rushdie returned to the wonder stories he grew up with for his latest book, a return to the 'high fabulism' he is so well known for

When the electronic latch clicks open for admission, the atmosphere inside is so hushed, I whisper my intention – an appointment with the agency’s most refulgent star of all: Salman Rushdie. The receptionist whispers back, in a manner that suggests I may have got the time, date, place or perhaps even the person, wrong.

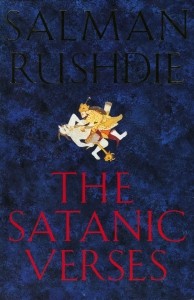

Within moments, Rushdie, equally punctual, arrives and breaks the spell. He is affable and warm in greeting. His striped linen shirt, cotton trousers, white socks and trainers avoid any hint of fashion except of the engagingly crumpled variety. We have met before, in London when Rushdie was still living under the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s fatwa (prompted by Rushdie’s 1988 novel The Satanic Verses), with no known address, bodyguards at his side, forced to travel in armoured cars. For the past 15 years he has lived in New York. His 12th novel, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, was published round the world this month.

Set in the near future after a storm strikes New York, Two Years features a gravity-defying gardener named Geronimo, and Dunia, princess of the jinn. These pre-Islamic folklore creatures, the novel tells us, “are not noted for their family lives. (But they do have sex. They have it all the time.)” They tend to be amoral, sneaky, lustful, power-hungry and irreligious. Rushdie adds his own chuckling rubric: “We humans have everything else, but not endless sex. Even endless sex after a couple of millennia probably gets a little tedious.”

He has trawled a sea of Indian and Arabian wonder tales for this novel, such as the Arabian Nights and the Panchatantra, hauling all of it into a baroque and barnacled fantasy narrative. “The source material is a great storehouse of tales I grew up with, that made me fall in love with reading,” he says. “I thought: ‘This is the literary baggage I’ve carried around all my life, and now I’m putting my bags down. Let’s see what happens when I unpack them and those stories escape into this place.’”

It might be the funniest of my novels. I have to say that even Andrew Wylie, when he was reading it, said he was laughing out loud, and that’s not easy to achieve

Although it took three years to write, it is – at fewer than 300 pages – one of Rushdie’s shorter books. It traverses the world of the 12th-century philosopher Ibn Rushd (Averroes), spanning New York and Fairyland, with walk-on parts for Isaac Newton, Henry Ford, Mother Teresa and Harry Potter. “Yes they’re all there to be squeezed in,” Rushdie says, as if in explanation. “It might be the funniest of my novels. I have to say that even Andrew Wylie, when he was reading it, said he was laughing out loud, and that’s not easy to achieve.”

One of Rushdie’s lifelong influences is Gabriel García Márquez, author of One Hundred Years of Solitude, the novel so closely identified with magic realism. “The problem with that phrase is that people only ever hear the word magic,” Rushdie cautions. “The point is that it is a way of trying to combine the fantastic and the realistic into a single narrative.”

This technique can be irritating, I suggest. There’s always a get-out clause: the hero can escape from cataclysm by, say, turning into a sparrow and flying off. “The point of any kind of imagined world is that is has to be coherent in its own terms,” Rushdie retorts. “It must not just be whimsical. If anything can happen, then nothing matters.”

His last book was the 600-page memoir Joseph Anton – the title was Rushdie’s alias in hiding. As well as the fatwa, he describes his cosmopolitan Indian middle-class childhood: one boy, born in 1947, with three sisters, and the shock of his arrival in England in 1961 to board at Rugby. (An early awakening was the graffito scrawled on a school wall “Wogs go home”.) His love for his two sons, Zafar (born in 1979) and Milan (1997), shines through, and the remorse of his failed marriages to their mothers – the late Clarissa Luard and Elizabeth West – is almost unbearable to read.

He and fourth wife Padma Lakshmi divorced in 2007. Press prurience – in his memoir, he describes watching Lakshmi “pose and pirouette” for the paparazzi – is the one topic that provokes any hint of ire: “I don’t have a wild life. I don’t go out more than anyone else does. The difference is that whenever I go out, someone takes my picture and puts it in the Daily Mail. It’s pathetic. Writer goes out in the evening. So what? People can do whatever the hell they want.”

Spending several years finding ways of telling the truth “as clearly and accurately as he could” wore him out. “I think what happened is that after I’d finished writing the memoir, I kind of got sick of telling the truth. I thought: ‘It’s time to make something up.’ I had this real emotional swing towards the other end of the spectrum, towards high fabulism. I had so much enjoyed writing the books for my sons, Haroun and the Sea of Stories and Luka and the Fire of Life, that I thought about that source material again, not for children but for grown-ups.”

Despite the impact of the fatwa, Rushdie is still drawn to the twin dangers of religion and faith. He has said, bluntly, that in the end, religion itself will make people sick of God. “Maybe that’s slightly optimistic,” he says. “The number of terrible things being done in the name of religion might be piling up. At some point it might occur to people that the problem lay in the idea of religion. Look, I’m fairly open about not being religious, to say the least, but in the book, it’s a conflict because that’s one point of view. The other is also there, which is that people will increasingly turn towards religion.”

This move towards faith, everywhere you turn, still puzzles him. “If you’re a child of the 1960s, one thing that never occurred to us was that religion would become powerful again. It seemed like a busted flush. It’s not that people didn’t believe in various gods, but the idea that this would come to orchestrate the public discourse would have seemed impossible. If someone had said that to me in 1968 I would probably have laughed.”

But Rushdie would rather not be making headlines: “I’d rather be back in the books section. I’m stuck with it. It feels a bit like a millstone because I’ve got other stuff to talk about. On the other hand, the question of religious fanaticism has become so central to all of us, we all have to think about it. At least I can do my best to use the experience I have to try to respond as an artist.”

He perceives the Islamic revival as “a narrative of power which can confront overweening Western power, and make otherwise very powerless individuals feel as if they’ve got some power. And then it helps if you’re a psychopath and feel like cutting people’s heads off.”

He dislikes the word “Islamophobia”. Extremism does not inhere in any particular religion or part of the world. The issues are wider and deeper: “It seems to me that if I don’t like your ideas, it must be OK for me to say so. If you think the world is flat, you have the right to say so, and I have the right to say you’re a fool. If you believe in God and I don’t, it must be legitimate for me to say your belief is full of crap ... The point about ideas is that they should engage with each other, not be ring-fenced. It’s a quite different matter to say there should not be racial prejudice against people. Of course there shouldn’t be. The colour of skin is a fact; religious belief is an opinion. It seems to me quite legitimate to have counter-opinions to any opinion without being called a name.”

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights by Salman Rushdie (Jonathan Cape)

The Guardian