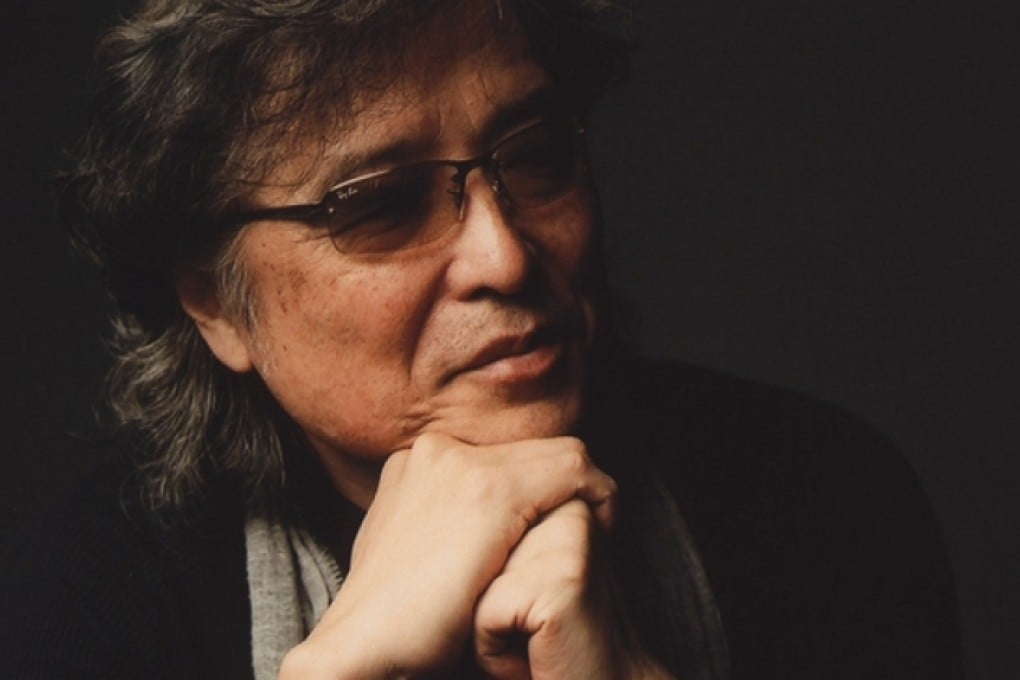

Soji Shimada, Japanese god of mystery, is still thrilled to be making a killing

Shimada's debut, The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, has just been reissued in a new English translation

Described as Japan’s “God of Mystery”, Soji Shimada studied art at university and worked as a truck driver and musician before he published his critically acclaimed debut, The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, which was shortlisted for the Edogawa Rampo Award. The pioneer of the “shin-honkaku” (new orthodox) genre of logical mysteries, Shimada is credited with triggering the late 1980s boom in mystery novels that continues in Japan to this day. Subsequent works include the Detective Mitarai series and the Detective Yoshiki series, and he has also written a number of humorous mysteries. Born in Hiroshima prefecture and now 67, Shimada still plays the guitar and is a big fan of The Beatles and Sherlock Holmes. Pushkin Vertigo published a new translation of The Tokyo Zodiac Murders last month.

Why is The Tokyo Zodiac Murders still popular after so many years?

One of the key elements of the story is that it has a very clever trick in the middle. When you decorate a Christmas tree, you look at the ornaments and not at the trunk. I came up with the idea for the book and the trick after hearing of a real incident in about 1978. At the time, there were some strange banknotes circulating with sticky tape on them. I don’t want to spoil the story for anyone who has not read it, but I was able to work that into a brilliant idea that is the centre of the story. That keeps the story fresh today.

Why did it take you so long – you were in your 30s – to write that first novel?

I was thinking that when I reached 30 I should be mature and able to understand the rules of society and the world. I should be able to think as a mature person, to understand how women think and so on. So I wanted to be mature when I wrote my first book. But when I turned 30 I found out that I was not mature at all.