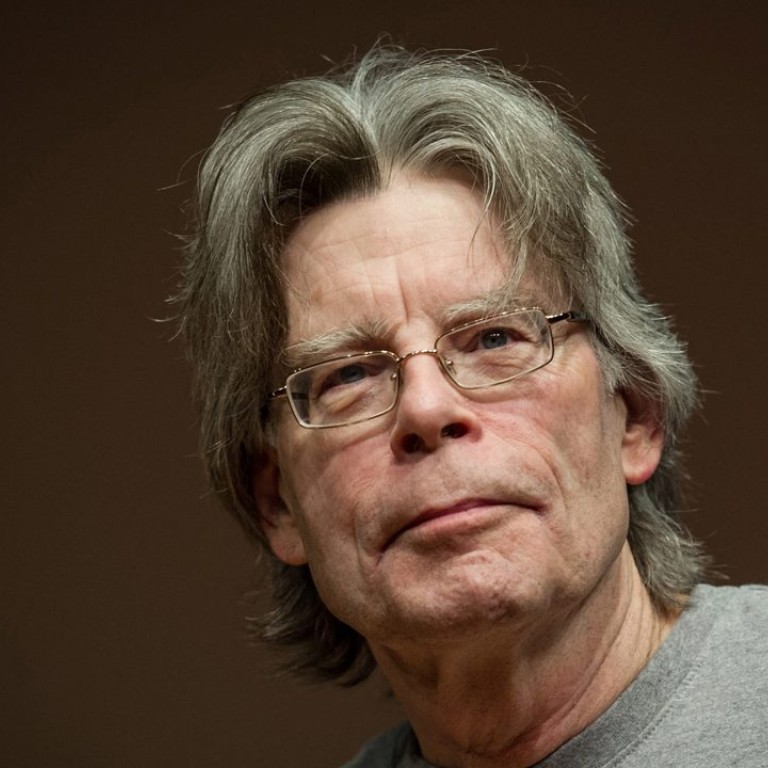

Book review: with The Bazaar of Bad Dreams, Stephen King reflects on death in small doses

This collection, with its recurring themes of old age and the final countdown, lets us know the author is at peace with his own mortality

by Stephen King

Scribner

In the introduction to this latest doorstop collection of short stories, Stephen King acknowledges he’s primarily a novelist but will always be fond of more compact tales. “There’s something to be said for a shorter, more intense experience. It can be invigorating, sometimes even shocking, like a waltz with a stranger you will never see again, or a kiss in the dark, or a beautiful curio for sale laid out on a cheap blanket at a street bazaar.”

Because these curios belong to King, many of them have teeth. In the merciless Mile 81, something awful happens to the people who wander into an abandoned highway rest stop. In Bad Little Kid, a chubby, orange-haired little boy with a beanie cap torments a man with a level of cruelty most bullies can only aspire to attain. In That Bus is Another World, a man stranded in a traffic jam sees something ghastly happen inside the bus idling next to his taxi. In UR, which was originally written exclusively for Amazon in 2009, a college professor discovers his pink Kindle can download books from another dimension.

But the majority of these 20 stories, novellas and (two) poems, roughly half of which have been published elsewhere, return again and again to the subject of old age and mortality. Death – or more specifically, the fear of death – is the basis of all horror, and King, who is 68 and has always shared an intimate relationship with his constant readers, is clearly contemplating his age and wants to let us know that he’s OK with his own finality. He seems content and creatively satisfied. He remains scarily prolific, and his fan base remains strong. So he knows he has an audience willing to hear him muse about “The End” and, as is his speciality, comes up with myriad ways to explore the subject.

The Dune, about an old judge in a rush to prepare his will, has a diabolical twist ending worthy of O. Henry. Batman and Robin Have an Altercation blends a real-life road rage incident King witnessed with a touching portrait of a senile, incontinent man on his weekly Sunday lunch outing with his grown son.

“I think that most people tend to meditate more on What Comes Next as they get older,” King writes in his introduction to Afterlife, which begins with a terminally ill man passing away. The Raymond Carver-flavoured Premium Harmony is slight, with a telegraphed ending. But something about its bickering husband and wife resonates; perhaps it’s their almost mundane acceptance of the inevitable. Herman Wouk is Still Alive, which uses a Rube Goldberg construction to recount a terrible automobile accident, is emotionally cool despite its great tragedy: this stuff happens.

Death may be inevitable, King says. But to fret about it or dwell on it is a waste of time

Mister Yummy, about the denizens of a retirement home, marks a rare turn for King: the central character is gay. The story, unfortunately, also happens to be one of the worst in this hit-and-miss book, which lacks the momentum and urgency of Night Shift, his first (and best) short story collection, or Different Seasons, the omnibus of four fantastic novellas that spawned three movies (Stand By Me, The Shawshank Redemption and Apt Pupil).

But the best stories in The Bazaar of Bad Dreams are the ones that read like they meant something to King, like they were just more than ideas he decided to explore in a story. A Death, which bears the easy, plaintive prose of Kent Haruf, follows a sheriff preparing to go through with the hanging of a man who may have been falsely convicted of murder. Obits channels the snark and cynicism of contemporary culture as its hero, a writer of celebrity death notices for a Gawker-like website, discovers he can kill people by writing their obituaries while they’re still alive. Summer Thunder, the touching post-apocalyptic story that concludes the book, ends on a note of lovely melancholy. Death may be inevitable, King says. But to fret about it or dwell on it is a waste of time when life, even at its most difficult, can bear so many rewards.

Tribune News Service