How Somerset Maugham’s China connection gave him a wealth of stories

The writer sought out expatriates in Hong Kong and other outposts of empire and used their tales of boredom and betrayal in his works – not always to the delight of his sources

December 16 marks the 50th anniversary of the death one of Britain’s most famous and celebrated writers, a man who was greatly influenced by his travels in China and Southeast Asia. Although William Somerset Maugham was born and died in France, and his ashes were scattered in England, some of his most admired work was inspired much closer to these shores.

Maugham was already a successful novelist and playwright when he made his first four-month journey to China via Hong Kong with his private secretary and lover, Gerald Haxton, in 1919. This and subsequent trips to Asia provided a rich source of material that was to help forge his reputation as a writer able to capture the hypocrisy, isolation and repressed agony of formal expatriate life with an exquisite sensitivity.

The China expeditions inspired a critically acclaimed series of vignettes and short sketches titled On a Chinese Screen and arguably his most entertaining novel, which was inspired by a notorious scandal revealed to him while in Hong Kong.

The Painted Veil, published in 1925, is set in Hong Kong, where young frivolous heroine Kitty Fane, recently married to the devoted but dull and taciturn microbiologist Walter, finds her social standing much beneath that which she had enjoyed in England.

“Their house stood in the Happy Valley, on the side of a hill for they could not afford to live on the more eligible but expensive Peak,” writes Maugham, never slow to pick up on petty social hierarchy.

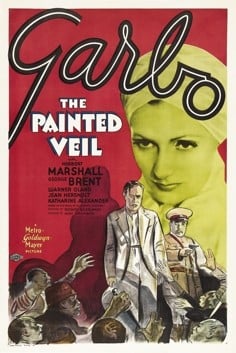

Bored and restless, Kitty soon finds herself in bed with the handsome, conceited and amoral Charles Townsend, the married assistant colonial secretary. The scandalous narrative unfolds at a breathless pace and, not surprisingly, has been made into films, the first starring Greta Garbo in 1934 and the most recent with Naomi Watts and Edward Norton in 2006.

Maugham excels while dealing in all his strongest literary suits – a foolish and immature woman, a dysfunctional marriage, hypocritical social norms, snobbery, moral ambivalence, repressed sexual desire and, of course, the seductive, irresistible cad.

“The portrait of Kitty Fane is one of Maugham’s finest fictional achievements; he completely inhabits and possesses Kitty,” his biographer, Selina Hastings, writes in The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham. “There is no doubt at all that the author knows precisely what he is talking about when he describes the almost physical pain Kitty suffers in her craving for sex with big bad Charlie Townsend,” she adds, referring perhaps to Maugham’s own devotion to his partner of 25 years, the handsome, charismatic and gregarious American playboy, Haxton.

The book caused a sensation and had to be amended after a successful legal action from a Hong Kong couple (the Lanes) was followed by another threat of legal action, this time from Hong Kong’s acting colonial secretary, Arthur Fletcher. On legal advice, the publishers changed the name of Hong Kong to the fictional city of Tching-Yen and the names of the central protagonists were changed from Lane to Fane. Unfortunately, several thousand copies of the book had already been printed. These were recalled, but a first edition of The Painted Veil, complete with the Lanes, is now a prized collector’s item.

That first China trip also gave Maugham much needed respite from his increasingly unhappy marriage. For years Maugham tried to maintain a veneer of respectability as a married man and devoted father, but the truth was he was miserable at home, while his wife, Syrie, whom he married in 1917, became increasingly resentful of his double life.

Maugham was happiest travelling with his soulmate Haxton and there was no chance of him agreeing to his wife’s repeated requests to accompany him on his adventures. “I go to seek ideas and when I am with you I get none, I am very sorry but that is the brutal fact,” he told her.

Most of those ideas were supplied by expatriates in China and later Singapore, Malaysia and the Pacific islands. He needed the gregarious Haxton to break the social ice at the hotel bar or over the club billiard table, so the shy and stammering Maugham could carefully listen to their often lurid and private tales told under the hum of a ceiling fan.

Maugham is quite brutal in his quest to find people and stories to collect, like an etymologist gathering insects, and it caused a great deal of resentment at the time

“They are bored with themselves, bored with one another,” he wrote, and was amused by those stalwarts who spent 30 years in China without learning a word of the language or even venturing into local towns.

Maugham found it impossible to judge others or be shocked by their behaviour, and his writing was always “unbigoted”, as novelist Paul Theroux once put it. He developed a sensitive nose for hypocrisy and sanctimonious drivel, and found an easy target in the army of Protestant missionaries sent to proselytise in China; they feature large in On a Chinese Screen.

“To Maugham, the Protestants appeared self-satisfied, ignorant and overall gauche in their dealings with the natives,” says Dr Julia Kuehn of the University of Hong Kong, who wrote a paper on Maugham and missionaries. Part of Maugham’s contempt for the Protestant missionary community was their lack of professionalism, lack of industry and his own inherent snobbery.

“They may be saints but they’re not often gentlemen,” he wrote, although elevated English social class was not a prerequisite for being a subject in Maugham’s work and his characters in the book also include coolies, a refined Chinese mandarin, sea captains, a Mongol chief and a nun.

“He is looking for human encounters not places,” says Kuehn, who does not think there is much substance about China in his work. Instead Maugham is quite brutal in his quest to find people and stories to collect, like an etymologist gathering insects, and it caused a great deal of resentment at the time. Hospitable colonial types divulged their secrets late in the night over one too many whisky and sodas, only to find themselves the subject in a work of bestselling literature.

“It was an intimacy born on their side by ennui or loneliness that withheld few secrets but one that separation irrevocably broke,” wrote Maugham. “It was the most entrancing game in which I had ever engaged.”

However, his detractors claim this reveals his fatal flaw as a writer. They say Maugham was cynical and described his characters in colourful microscopic detail, but ultimately did not care for them a great deal.

Before he died just a month short of his 92nd birthday, at the American-French hospital near his villa in the south of France, he described himself as “a relic of the Edwardian era”. One of the bestselling authors and playwrights of his time and an extremely wealthy man, he died inconsolably miserable and bitter.

He resented the fact that he was not considered one of the great artists of the English language. “Only the mediocre are always at their best,” wrote Maugham.

He once claimed his considered view of humanity was spoken by one of his characters. “The conclusion I came to about men I put into the mouth of a man I met on board a ship in the China Seas,” wrote Maugham. “‘I’ll give you my opinion of the human race in a nutshell, brother’, I made him say. ‘Their heart’s in the right place but their head is a thoroughly inefficient organ’.”