Why are the animals always male in children’s books?

Frances the badger, Olivia the pig and Lilly the mouse are very much the exception to the rule in children's literature. Does it matter? And what would be the impact on young girls of reading more stories with female characters?

Every night, my daughter picks out bedtime stories from the picture books on her shelf. She doesn’t know how to read yet, so she can’t know that my husband and I are deviating from the text when we gender-swap Pete the cat or Elliot the elephant, and there’s nothing in the books’ illustrations or plots to suggest that these characters need to be male.

It took me a while to notice the disparity, but I soon realised I’d have to do on-the-fly editing if I didn’t want my daughter to think that the non-human world is predominantly the province of males.

A 2011 Florida State University study found that just 7.5 per cent of nearly 6,000 picture books published between 1900 and 2000 depict female animal protagonists; male animals were the central characters in more than 23 per cent each year. (For books in which characters were not assigned a gender, researchers noted, parents reading to their children tended to assign one: male.) No more than 33 per cent of children’s books in any given year featured an adult woman or female animal, but adult men and male animals appeared in all the books.

While there are a handful of exceptions, like Frances the badger, Olivia the pig and Lilly the mouse, they are the exceptions that prove the rule.

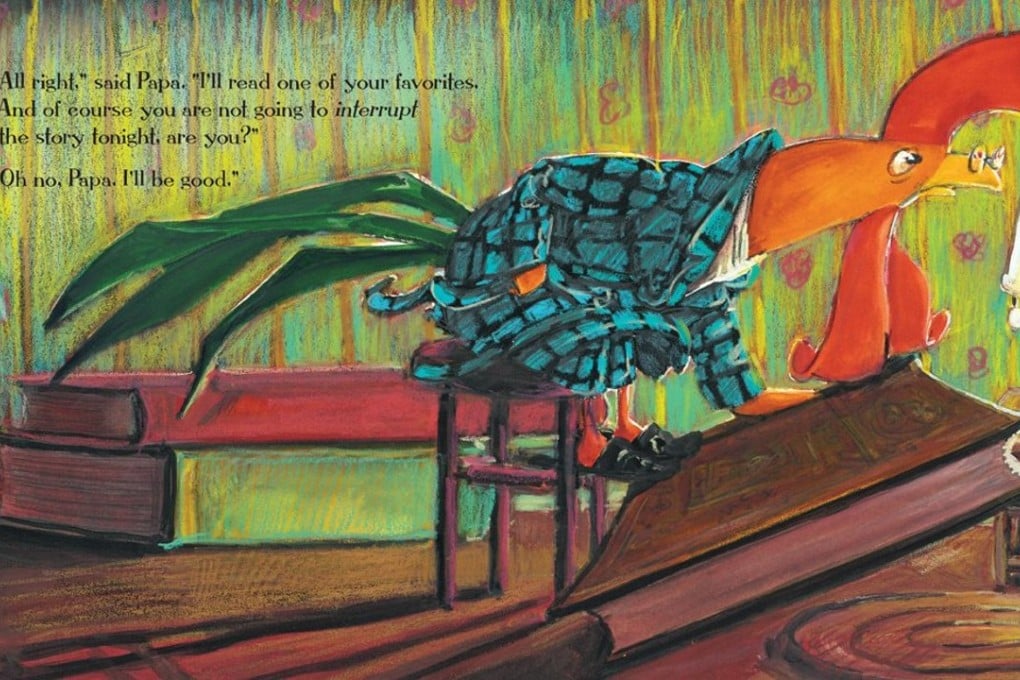

Of the 69 Caldecott Medal and Honor winners since 2000, just four – Kitten's First Full Moon, Interrupting Chicken, Olivia and A Ball for Daisy (which has no text but identifies Daisy as “she” on the jacket copy) – have animal protagonists that are clearly identified as female.