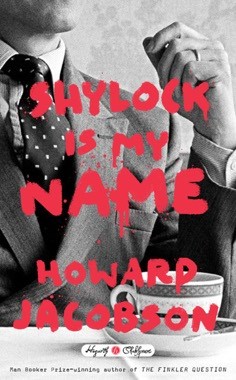

Book review: with Shylock Is My Name, Howard Jacobson subverts and deepens our understanding of Shakespeare

At times it verges on propaganda, but the Booker winner’s novel seethes in places with raw feeling, and delivers a final twist that rewards your perseverance

by Howard Jacobson

Hogarth

The figure of the unassimilated Jew, defiantly “other” in skullcap, gabardine and fringed garment, has been a source of Gentile unease for centuries. It is what fuels the plot of The Merchant of Venice, and its corollary – Jew-baiting – is what gives the play its uncomfortable immediacy.

Part of its disquieting power, in Shakespeare’s telling, is its unstable moral perspective: are we watching a play about anti-Semitism, or an anti-Semitic play? Unlike Malvolio, whose expulsion from the festive world of Twelfth Night is a cause for straightforward rejoicing, Shylock’s fall leaves us jangling with unresolved emotion, and the character lingers.

The new novel by Man Booker winner Howard Jacobson, part of a series of Shakespeare retellings commissioned for the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death, makes bold use of this haunting persistence. In its opening scene, Simon Strulovitch – “a rich, furious, easily hurt philanthropist with on-again off-again enthusiasms, a distinguished collection of 12th-century Anglo-Jewish art … and a daughter going off the rails” – encounters Shylock in a Cheshire graveyard, transported to 21st-century England, but otherwise much as Shakespeare left him.

SEE ALSO: A tale of two concerts: Dieudonné vs Russell Peters

Among Strulovitch’s fitful enthusiasms is the question of what it means to be a Jew – the Finkler question, essentially – and Shylock, who has had plenty of time to reflect on the matter (and who also knows a thing or two about errant daughters), provides him with a natural interlocutor. Locked in the limbo of his own circling rage and regret, Shylock functions as a phantasmal projection of Strulovitch’s conscience, but he is also very much a free-standing character (Jacobson’s relaxed, garrulous style allows both), interacting with other people, and after Strulovitch invites him back to his house, the two men strike up a friendship.

Meanwhile in the Christian world, as per the original, a complicated romcom intrigue assembles itself, with a gay aesthete named D’Anton taking the Antonio role, a Porsche-driving heiress with a reality TV show that combines cooking and counselling playing Portia, a brainless football player with a thing for Jewish girls standing in for Gratiano, and so on. No one in this prosperous corner of Cheshire’s “golden triangle” needs to borrow money from Strulovitch, but dangerous bonds link Gentile and Jew nevertheless.

The Strulovitch/Shylock material, which consists mostly of talking and thinking, is where the novel excels. Jacobson knows these worldly, embattled Strulovitch types, with their lurching atavisms and exasperations, inside out. He has done them before, but the tumult remains raw and seething, and Shylock’s presence as accelerant gives it all a freshly tragicomic intensity.

There is something ingenious in the way Jacobson re-engineers the love plots from the original so as to bring about his own large surprises. But the actual execution is crude in the extreme. Flimsily conceived embodiments of vacuousness or effete viciousness, the Christians are also almost all unabashed anti-Semites. D’Anton and Plury (the Portia character) amuse themselves playing “Jewepithets” (“moneybags”, “pig refuser”); Gratan has been in trouble for giving a Dieudonné quenelle (a form of Nazi salute) on the football field. Some of these qualities, of course, have their warrant in Shakespeare, but there they form part of a coherent set of interests and motivations drawn from an observed cultural reality, whereas here we are in a realm of pure propaganda.

And yet the novel remains compelling, and if you can ignore the thinness of these sections, there is actually an intriguing thesis being developed. In an earlier incarnation as an academic, Jacobson co-wrote a wonderful book on Shakespeare with the late Wilbur Sanders, Shakespeare’s Magnanimity, and perhaps the most enjoyable thing about Shylock Is My Name is, fittingly, the astute way in which it reads and rereads the play it was commissioned to retell.

There are two big twists at the end. One, involving foreskins, is a bit silly. But the other, in which one of Shakespeare’s great speeches is reallocated to (and reconceived by) the last character on earth you’d imagine giving it, is inspired. It does what any good literary subversion should do: deepens and enhances one’s appreciation of the original.

The Guardian