What Bowie read: a rock’n’roll polymath’s eclectic reading

The late artist was a voracious bibliophile, and incorporated many literary references from a huge variety of sources into his work

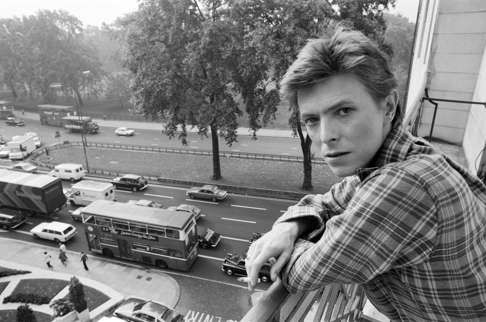

It’s long been clear that David Bowie was a polymath, an artist as much as a musician, that “chameleon, comedian, Corinthian and caricature” he wrote of in his 1971 song The Bewlay Brothers. But what can we make of his literary legacy, of his influences and output as a writer?

It started and ended in a theatrical tradition. “When I was a teenager,” he said in 2000, “I had it in mind that I would be a creator of musicals.” And there are traces of the native talents of Lionel Bart and Anthony Newley in his earliest songs. In another life he might have ended up at London’s Theatre Royal Stratford East or the Royal Court. The lyrics on his 1967 debut album David Bowie are a series of vignettes that seem destined for the stage: a child-loving ex-soldier is accused of paedophilia, a lesbian and/or trans man looks back on how she joined the army by passing as a man. His material was outré even then, but his failure to attract mainstream musical theatre merely pushed him into further experimentation.

SEE ALSO: David Bowie’s tailor – a Hong Kong icon fit for a prince, presidents and the Thin White Duke

He then worked with Lindsay Kemp, mime artist and theatre director, honing some skills in non-verbal expression. But learning mime did not stem his aptitude for words; it gave him a whole new vocabulary. Claiming his lineage from Shakespeare’s favourite clown William Kempe, Lindsey Kemp mentored him in the deep traditions of the stage as well as avant-garde theatre. Kemp’s adaptation of Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers clearly turned young Bowie on to that great dramatist and poet of the gutter, as he would later acknowledge in his 1972 paean to decadence, The Jean Genie.

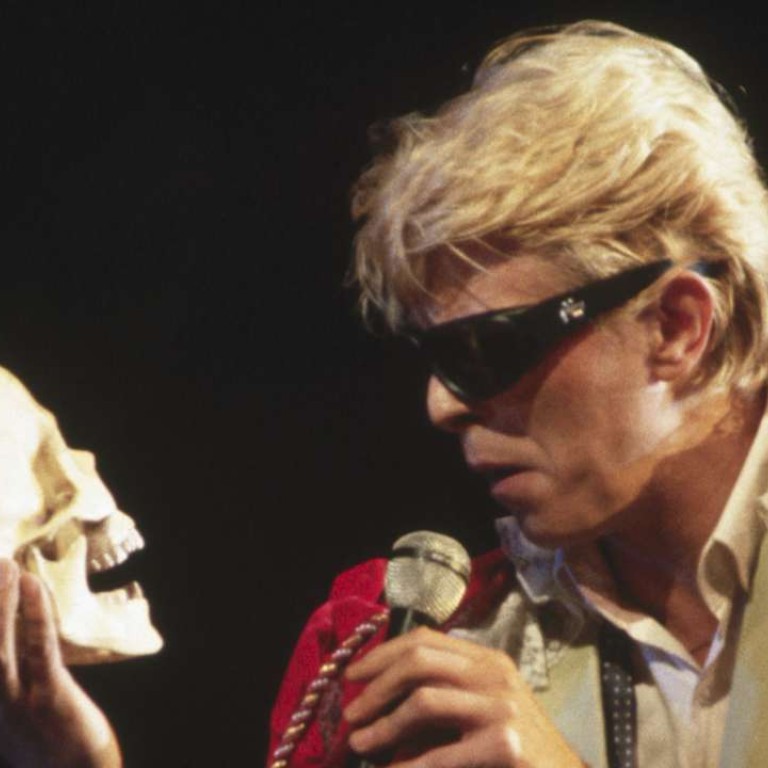

Like all good authors, Bowie was always ready to kill his darlings, but murdering Ziggy Stardust on stage gained him instant mystique and a trademark modus operandi. After a brief stint as Aladdin Sane, his next writing project was a theatrical adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, abandoned when Sonia Orwell denied the rights. The songs that remain are rather wonderful, particularly the soaring Big Brother and the plaintively haunting We Are the Dead. They end up on the second side of Diamond Dogs (1974), his darkest, most apocalyptic album.

But by now his life seems to have entered into a dangerous dramaturgy. Much of the 1970s saw a series of doomed characters in search of a homicidal author. Lost in a tailspin of drugs and paranoia in Los Angeles, each successive assassination merely brought him closer to killing himself. He needed artistic salvation as much as anything.

And here’s where I come in. Just as I had followed every literary reference in Bowie’s output from The Jean Genie (aged 11, I was looking up “Genet”) so I sought out Brecht at the very time I was trying to write myself. Threepenny Novel became the initial influence on my first novel The Long Firm, and I like to think it was its Brechtian qualities that Bowie admired when he came to praise it. But, of course, I kid myself that I might be part of a canon. Like all great writers, Bowie was a furious reader, so much so that when he issued his official reading list in 2013, I didn’t even make the top 100 (ah, such fleeting glory … ).

SEE ALSO: David Bowie remembered – a Hong Kong journalist’s fond memory of his 2004 concert and impact on the city

The list is wonderfully eclectic, everything from The Beano to Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual by Eliphas Lévi. Of British novelists, Orwell is there, as are Burgess and Bulwer-Lytton, and others he would have read growing up: John Braine, Keith Waterhouse, Muriel Spark. His own contemporaries are well represented: Ackroyd, Amis, Chatwin, McEwan and, of course, Angela Carter. Of my generation, the ones he influenced as mere teenagers when he first came on the scene, there are Sarah Waters and Rupert Thomson. Worthy choices both, particularly Thomson, something of a Thin White Duke of British fiction, sustaining a long career by constantly changing the way he writes. The rest of us simply owe Bowie for showing us all that work that never made it on the curriculum.

And in the last few weeks of his life the musical Lazarus opened off-Broadway, directed by Ivo van Hove, with his songs and a book by Enda Walsh. He gives his own swansong on the video of the title song, an astonishing performance, seemingly from the grave. “A farewell gift,” as producer and long-time collaborator Tony Visconti put it, “for now it is appropriate to cry.”

And applaud.

The Guardian