Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots in Hong Kong: director of The Witness on his theme and inspiration

- Alberto Mielgo’s vision of an alternate future Hong Kong came from how the city crams eras on top of one another, precariously bolting the future to the past

- He says the nudity and sex portrayed in his episode were part of a deeper theme about the nature of relationships and his own religious upbringing

Netflix surprised audiences back in March when it released Love, Death & Robots, an animated series heavily drenched in science fiction and aimed squarely at adults. While the streaming giant already had plenty of cartoons on its roster for older viewers, here was a show that laid out a vision much darker and more disturbing than anything Netflix had yet released.

Adding to the sense that this would definitely be weird were the names behind the project: director David Fincher from Fight Club and Se7en, and Tim Miller, a visual effects artist who made his feature debut behind the camera with the genre-busting superhero movie Deadpool.

The premise essentially asked: if Fincher and Miller ran Pixar, how twisted could it get?

One of the most visually startling episodes in the anthology, each created by a different artist, was the third instalment, The Witness, which takes place in a future Hong Kong. The story is based on a straightforward chase – a woman hears gunshots from the window of her flat in the early dawn and flees through the city streets pursued by the apparent killer – but comes with a twist.

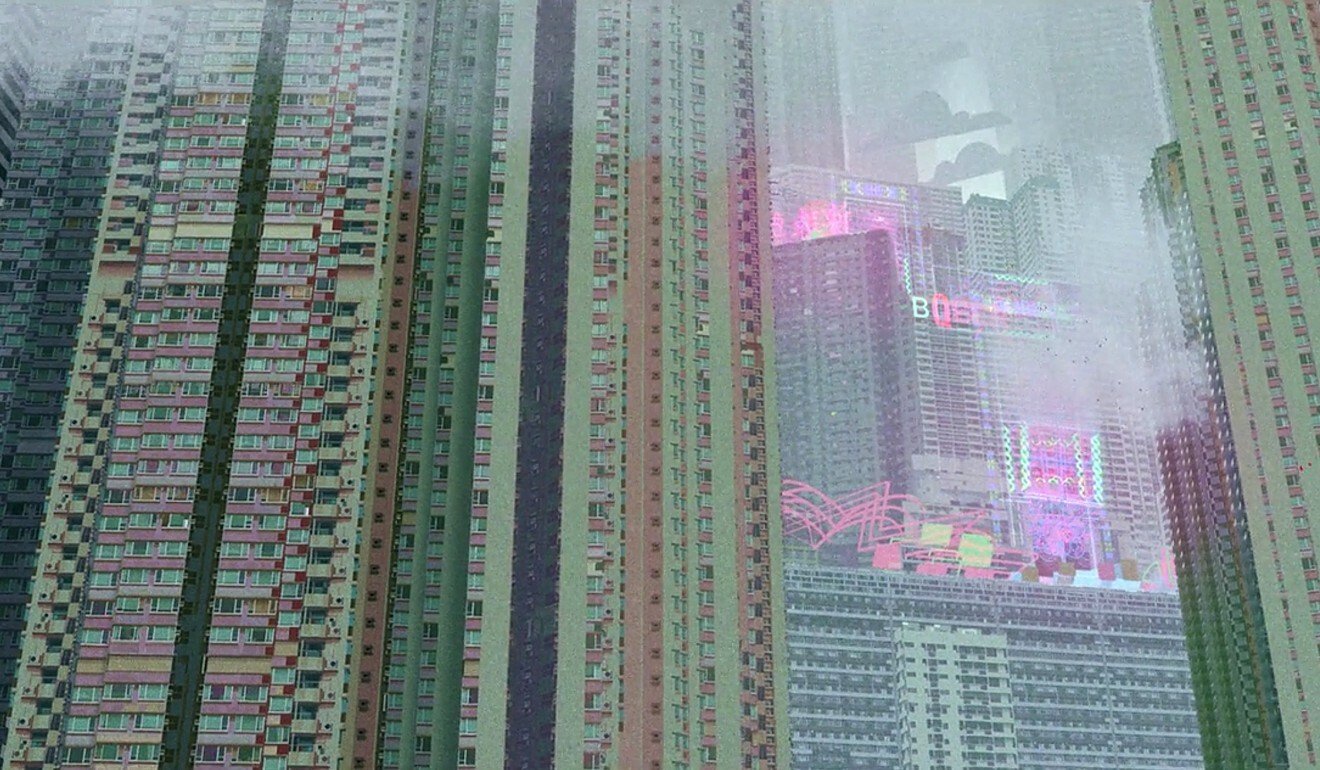

During the chase, the characters fling themselves into red taxis that pass under signs for “Tsim Sha Tzu” and the “Hoh Hom” subway station. They drive along streets with neon signs that pop in coral pink, violet and aquamarine, projected out into the canyons of buildings climbing upwards into white cloud. Storefronts are lettered in Chinese, Cyrillic and English, advertising, among other businesses, the “Bank of Banks”.

This slightly smudged sense of reality was what the director of the episode, Spanish painter Alberto Mielgo, says he was aiming for. And although the episode has been criticised by some in the media for its portrayal of women – the protagonist spends half her time running through the streets with her shimmering red kimono half-open – the director says the upfront sex is deeply rooted in the larger message of the film.

Mielgo’s involvement with the series began when he was approached by its supervising director, Gabriele Pennacchioli, who put him in touch with Fincher and Miller, both fans of his previous work. In the initial round of meetings with Blur Studio (Miller’s visual effects company) the directors emphasised they wanted the series to take a different path with the medium, a risk that made sense to the painter.

“I felt animation needed a drastic revision and appetite,” Mielgo says. “That was very much what we were trying to do with this show. To create something with the ingredients that mainstream animation does not usually have … horror, sex, anything that is for an adult audience.”

But Mielgo did not yet have an idea to offer them. He searched for inspiration by going through a folder of photographs he had been collecting over the years, taken from online and his travels. Two images caught his eye: one of Hong Kong’s Kowloon district from the internet and the other the interior of a flat in which he lived for a few weeks in Berlin, a place where he could see the people living inside apartments in other buildings. “And that was very much how I started thinking about a crime that happened across the street,” he says.

Netflix liked the idea and Mielgo flew from Los Angeles to Hong Kong, where the artist says he got purposely lost for five days wandering around the neighbourhoods of Kowloon from 5am to 10pm, drawing, taking photos and storyboarding sequences, setting out the locations for the chase.

“I found – and I don’t know if this [is] right to do in Hong Kong – but I found every door was open. In the beginning I was a little bit shy, but then I was getting inside and getting inside and getting inside, and going onto rooftops and nobody said anything. I was very respectful, but I found Hong Kong was very welcoming in a way.”

This story is very much a representation in the shape of a thriller of difficult types of relationships into which I repeatedly fall

As the days unfolded, he found the city was an ideal backdrop for the theme of the episode. “It was funny. When I was thinking about The Witness, I realised that Hong Kong … is full of windows. You can feel there are different lives, and you feel there can be a lot of witnesses of something happening in the street,” he says.

“However, I had a feeling that those windows are a little bit empty. You cannot really see into them; they are a little bit dark. In a way, you might feel that if there is anything dangerous happening inside, nobody is going to see you, even though you are surrounded by possible witnesses.”

Mielgo was also drawn by how Hong Kong has crammed eras one on top of the other, with the future bolted precariously onto the past – decades of ways of living squeezed together and condensed. This is why he presented the city as otherworldly.

“The five days I was in Hong Kong, it felt really futuristic but is also feels really, really old. It has a lot of different ingredients from different times. But it doesn’t feel like the present. There is something about that city that makes me feel either in the future or in the past. I loved it. I wanted to represent that with the little messages I put in there. It was a very strange and beautiful feeling.”

Love, Death & Robots, while praised for its visual audacity, has also been criticised for its depiction of women, specifically using their bodies as nothing more than props for titillation or sexualised violence.

Mielgo, while aware of the backlash, says the nudity and sex portrayed in his episode were there for a reason. They are part of a deeper theme, which for him is about the nature of certain relationships and his own religious upbringing as a Catholic.

“This story is very much a representation in the shape of a thriller of difficult types of relationships into which I repeatedly fall … which are not necessarily based on love but on needs, on anything that is like an obsession more than love,” he says.

“In this case, the need and obsession is sex and temptation. These kinds of relationships are usually very difficult to end. For some reason, the lovers, they come back and they come back, and they both become a victim.”

With The Witness, which looks like it was shot live but consists entirely of paintings and 3D characters, Mielgo hopes to be part of a new wave in animation, one where works can stand alongside live-action films in festivals around the world.

For too long, he says, the genre has been relegated to marketing fare aimed at children. The Disney formula has been tremendously successful over past decades, copied endlessly by other studios such as DreamWorks, but with results that end up looking so similar that not even the audiences can tell the creators apart.

It is important that Fincher and Miller can “go completely wild and do something that is completely opposite,” he says.

“That is making people angry but is also making people really happy. It is creating a big reaction. I think that was the main purpose. I think that is a really, really good beginning for sure.”

Love, Death & Robots is available for streaming on Netflix