K-pop suicide sparks a reckoning on revenge porn, sexual assault and outdated attitudes in South Korea

- A petition of a quarter of a million signatures was given to the South Korean president calling for changes to laws

- South Korea’s laws on revenge porn, sexual assault and rape are outdated and need rewriting, says lawmaker Lee Jung-mi

The latest suicide of a popular South Korean singer has prompted calls in the country to overhaul laws on sexual assault and to more harshly punish revenge porn.

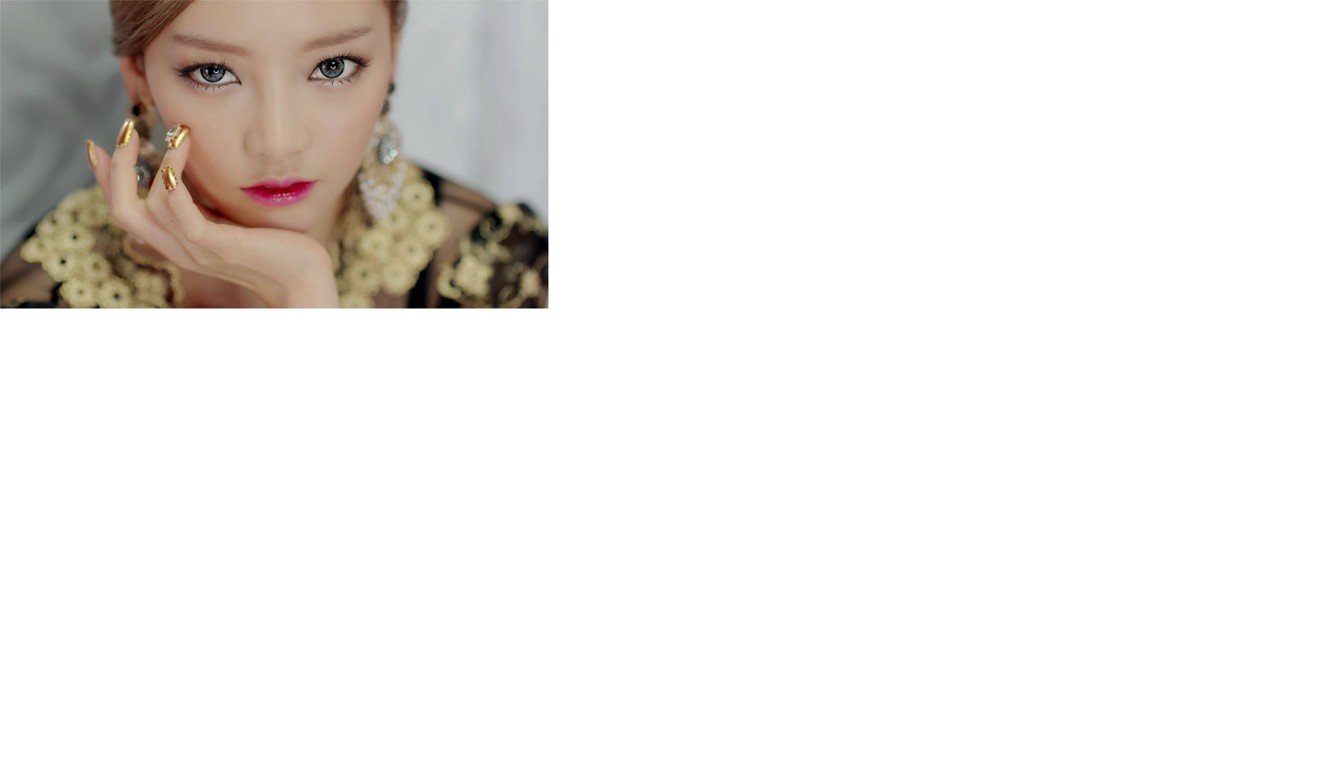

Goo Hara, 28, was found dead at her home in Seoul on Sunday. Her last message on Instagram showed her staring into a camera lens from beneath blankets on her bed with a message of “good night”. Police say a note was found at the scene in which she expressed hopelessness.

Many in South Korea were already aware of her past, which included assault by a former boyfriend who she alleged was threatening to release a sex video of her. The two most popular hashtags on social media in South Korea this week called for punishment of the ex-boyfriend and for the definition of sexual assault to be revamped.

A petition filed with the president’s office demanding changes to laws had one quarter of a million signatures. Lawmakers said it is time to push forward measures stalled in parliament that make it easier to impose harsh penalties on those who engage in revenge porn or clandestinely take sexually explicit videos.

Liberal lawmaker Lee Jung-mi of the minor Justice Party said in a social media post that Goo’s death shows that change is needed because the nation “cannot neglect illegal filming and circulation of videos”.

Lee in September 2018 introduced a bill to revise how South Korea’s criminal law defines rape. She said recent verdicts on sexual crime show the current standards don’t focus on consent but how much “resistance” there was from the victim.

President Moon Jae-in has called for a wide-ranging investigation of sex offences linked to the entertainment industry and ordered the reopening of inquiries into past allegations.

He issued a decree in June 2017 that set punishment of up to five years in prison, with the measure mostly pertaining to filming through hidden cameras.

Some of those who are fighting for changes to the laws say they are frustrated with the pace of change.

It’s still quite a dark reality compared to the rest of the world. I can tell you that I will pay more attention on gender equality

“The current justice system sends a message to women that it will never be able to protect them,” said Yun Dan-woo, a writer and women’s rights activist.

Some recent cases illustrate critics’ concerns. In May 2018, a male judge ruled that a man wasn’t guilty of raping a woman who walked to a motel with him, according to media reports. Surveillance video presented as evidence showed the man pulling the woman. The judge acknowledged she had rejected sex but ruled this wasn’t a case where she was in danger, the reports said.

In a case in November, a male judge found a man not guilty of rape even though he had sex with a woman against her will. The judge ruled she gave consent by holding hands and giving the defendant an extra piece of meat at a restaurant, according to the legal journal and local media.

Goo was a member of the group Kara, which had nearly a decade-long run as a top act in the notoriously fickle K-pop music industry. One of group’s biggest songs, Step, garnered nearly 100 million views on YouTube, helping Goo win fame in Japan, China and other major markets outside Asia.

In Koo’s case, a judge found her ex-boyfriend guilty of assault yet acquitted him of filming Goo naked and trying to blackmail her.

Although the laws on clandestine recording could be applied to revenge porn – posting without permission explicit images of individuals that may be taken in acts including consensual sex – that sort of prosecution is almost unheard of in South Korea. More than 40 US states have laws banning the practice, as do other countries.

Proponents of more stringent measures say they want to act now while Goo’s death is fresh in the public mind and may give a push for change.

“Korean society has this misconception of rape of always being done by some random monster who comes out of nowhere in a dark alley at night, which is why it doesn’t acknowledge that someone close and intimate is more likely to be the perpetrator,” said Claire Park, an activist at the Korea Sexual Violence Relief Centre.

If you, or someone you know, are having suicidal thoughts, help is available. For Hong Kong, dial +852 2896 0000 for The Samaritans or +852 2382 0000 for Suicide Prevention Services. In the US, call The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on +1 800 273 8255. For a list of other countries’ hotlines, please see this page.