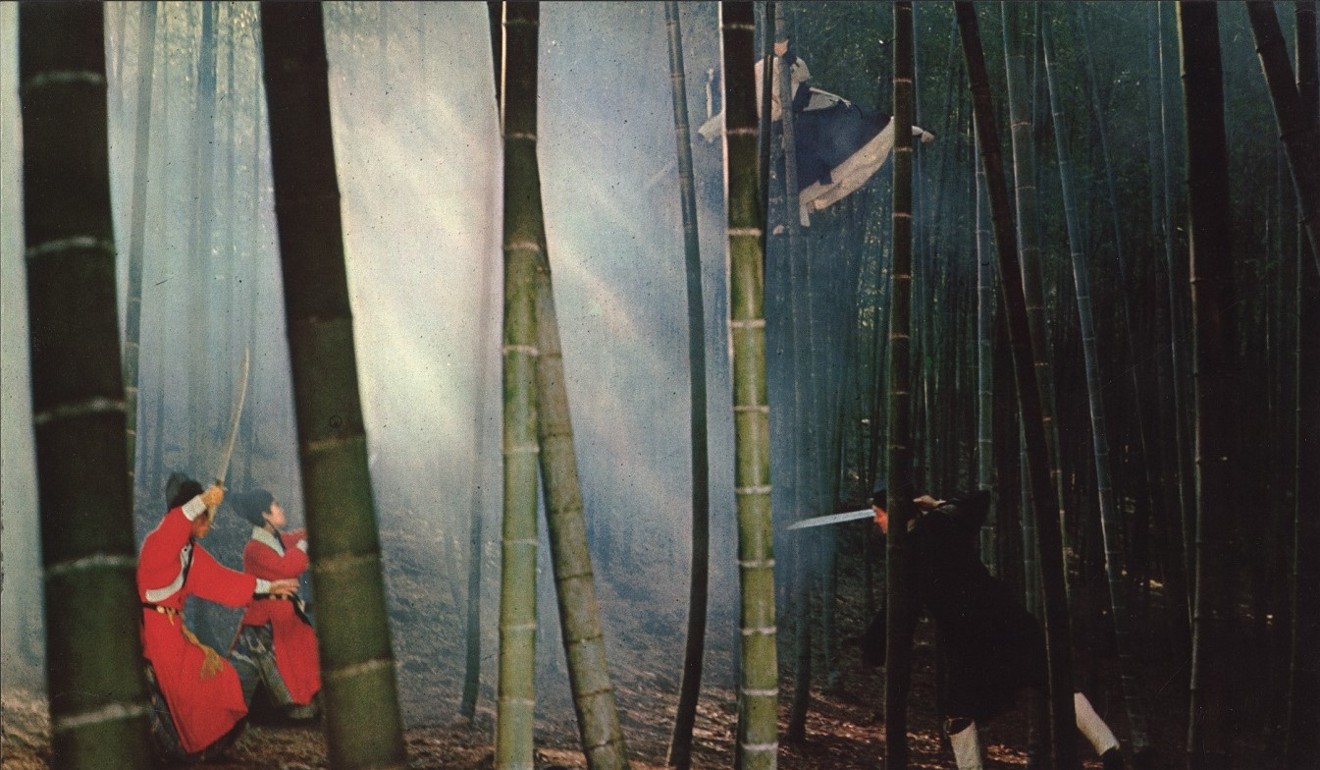

Hong Kong martial arts cinema: A Touch of Zen, King Hu’s 1971 wuxia classic

- The third martial arts film the Chinese director made, this is the story of a fugitive and a group of monks who use their skills to overcome daunting odds

- Hu planned the martial arts scenes with choreographers, and showed his brilliance in the editing room afterwards

King Hu’s epic 1971 martial arts film A Touch of Zen transcends genres to stand on a par with cinematic classics such as John Ford’s The Searchers and Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai . The aim of the three-hour feature, set in the Ming dynasty, is to express the ineffable qualities of Zen Buddhism. The film’s artistic qualities received some recognition at the time, and it won the Technical Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1975.

A Touch of Zen was the director’s third wuxia film, following 1966’s groundbreaking Come Drink with Me and 1967’s box-office hit Dragon Inn . Hu, who was born in Beijing but moved to Hong Kong in 1949, made his first films at Shaw Brothers studio, but joined Union Films in Taiwan to make Dragon Inn.

That movie made so much money that Hu and Union Films were able to build a martial arts film studio in Taiwan, which was used to shoot much of A Touch of Zen.

A Touch of Zen is roughly divided into three parts. The first section focuses on an individual, and generally presents events from the point of view of one character. The second is political, and looks at the characters working together to achieve their goals. The third part is philosophical, and expresses the ineffable nature of spiritual transcendence, or nirvana.

The story begins with Ku (Shih Chun), a failed scholar who makes his living drawing portraits, meeting Yang (Hsu Feng) at the ruined fort where he lives with his mother. After an unexpected tryst with Yang, Ku discovers that her father was murdered when he tried to report a corrupt eunuch of the Gestapo-like Eastern Chamber to the Emperor. Yang is now fleeing murderous Eastern Chamber spies.

Yang tells Ku that while she was on the run, she was helped by a group of Buddhist monks who sensed the evil intent of her pursuers. Although they are not invincible, the monks possess powerful martial arts skills, and they taught Yang to fight while she sheltered in the monastery.

In the fort, Yang and Ku are joined by more of her friends. As the enemy closes in, Ku harnesses their martial arts skills to win a battle against overwhelming odds.

The final part of the film adds a spiritual perspective by showing the abbot of the monastery (Roy Chiao) achieve nirvana after using his kung fu skills to save Yang.

Hu based A Touch of Zen very loosely on a story called The Heroic Maid, from the book Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio by Pu Songling, a 17th-century scholar.

Hong Kong martial arts cinema: everything you need to know

Hu, who was not a Buddhist, also wanted to represent the “supernatural flavour”, as he put it, of Zen Buddhism on the screen.

The director understood the expressive potential of martial arts as a uniquely Chinese art form. Lacking expertise himself, he relied on martial arts choreographers such as Han Yingjie to arrange the martial arts sequences, which he would then piece together in the editing room. The choreographers would discuss the broad outline of the action and the camera positions with Hu to set up the most cinematically effective performances.

One innovation was the use of trampolines in the martial arts sequences. Hu’s fictional heroes and heroines could perform what was called “Zen jumping” – although they could not fly, they were able to leap further and jump higher than those who had not trained in martial arts. Much of the elegance of Hu’s fight scenes was achieved through the gentle motion produced by trampolining.

A scene in which Yang dives from a tree in a bamboo grove to attack her enemies has gained much attention, mainly because it was referenced in a scene in Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon . The scene was constructed by the clever editing of stunts, choreographer Han said in an interview.

“The location was a forest in Taiwan, and it was quite dim, with only two hours of sunlight each day. Since the trees were three storeys high, using wires or trampolines was out of the question. In the end we put the camera in the middle of a lake next to a cliff, and took shots of the stuntmen diving into the lake, then cut it into the forest,” he said.

Hu saw filmmaking as extension of the arts in general. He was extremely well read – when he moved to Hong Kong from Beijing, he brought three suitcases of books with him – and was knowledgeable about classical Chinese painting, Peking opera, and Chinese history, all of which informed his filmmaking.

A Touch of Zen was the second of Hu’s films to feature Taiwanese actress Hsu Feng, who, along with Cheng Pei-pei, was one of the greatest actresses of the wuxia genre.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre. Read our martial arts film explainer.