Advertisement

Punk rock, music of protest, finds new voice in the Philippines rallying opposition to Duterte’s war on drugs

- There have been punk rock bands in the Philippines since the 1980s, but only in recent years have their music and musicians become virulently political

- As the voice of opposition to security forces’ bloody anti-drug operations and deadly attacks on rights activists, bands like Bad Omen draw big, angry crowds

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

The young Filipinos are making a lot of noise, sweating and surging as The Exsenadors belt out a protest song, and scream along to the lyrics “Kamatayan o kalayaan! Maghimagsik!”(Death or freedom! Rebellion!) at a concert north of Metro Manila.

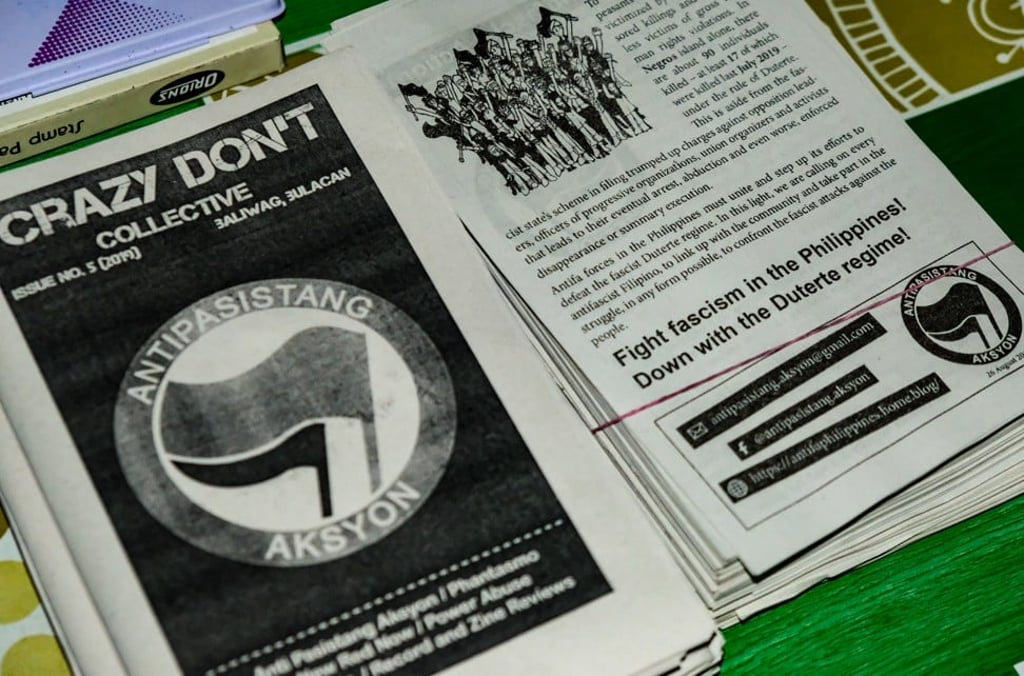

Organised by the Crazy Don’t Collective, February’s event in Baliuag, Bulacan province, featured dissident music from the Filipino underground punk rock scene, including a set by the band Bad Omen, and the crowd was on fire.

The sound of rebellion and revolt, punk rock is a loud and raucous shout at the establishment. The music has had a dedicated worldwide following for decades. In the Philippines, conditions are now ripe for punk to play a bigger role in anti-government protests.

Advertisement

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, elected in 2016, has built up a formidable strongman image. Like former Ugandan president Idi Amin, and Italy’s Benito Mussolini, he has pinned a number of the nation’s problems on select groups of citizens and unleashed violence to “resolve” them.

Advertisement

Duterte’s bloody “war on drugs” has ravaged the country, and although his popularity has waned recently, the Philippine security forces still routinely carry out often fatal anti-drug operations. Some observers estimate Duterte’s anti-drugs crusade has resulted in more than 30,000 casualties.

Ordinary civilian life has taken a hit, especially for the poorest in the country. Smoking in public has been banned, with sometimes severe penalties, including weeks-long jail terms.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x