Why a new generation of Singapore filmmakers have turned to social realism in their stories about the Lion City

- Many think of Singapore as a safe place full of rich elites, and films such as Crazy Rich Asians reflect that perception

- Films such as I Dream of Singapore and A Land Imagined look at the Lion City through the eyes of migrant workers and the poor

When a starry-eyed 27-year-old Muhammad Feroz Al Mamun left Bangladesh for Singapore, he didn’t think his dream would crumble to dust in the span of just two years.

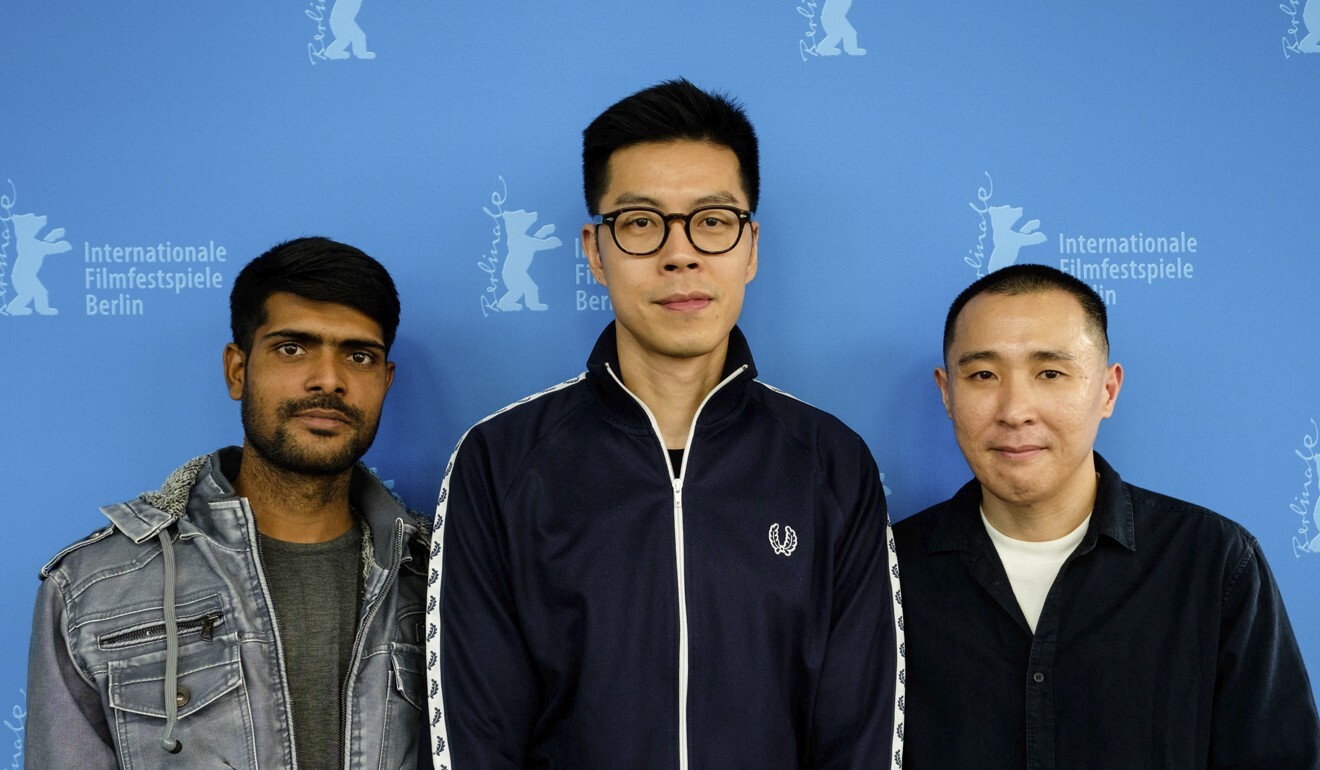

“I came from a very poor family, so I wanted to establish myself in Singapore. I expected to earn money then go back to Bangladesh to live a good life, but it’s actually very difficult for migrant workers to stay in Singapore,” says Feroz – who attended the 70th Berlinale International Film Festival in February with I Dream of Singapore director Lei Yuan Bin, producer Dan Koh and fellow cast member Ethan Guo.

Feroz’s journey is central to Lei’s latest documentary, which premiered to an international audience as one of the 36 feature films selected for the Panorama section of the festival in Germany. The film follows Feroz taking refuge at DaySpace, a sanctuary for unemployed migrant workers run by the non-profit Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) organisation, which helps low-wage and exploited migrant workers in Singapore. Feroz was stuck in limbo because of a work injury he had sustained on a construction site and sought help from TWC2.

He never received the compensation he deserved nor the legal right to continue working in Singapore. At the end of the documentary, Feroz is seen in bed, staring blankly into the camera, echoing the film’s opening scene.

Feroz says the “Bangladesh Dream” is to get a government job, but without the essential connections few people manage to secure one.

The “Singapore Dream”, as friends from his home village suggested, could be a good substitute.

“I was very curious, a bit flattered, and also amused that they look up to Singapore as a very rich and safe country with nice people that’s very nice to work in,” Lei, the director, says.

He says that, even though migrants’ dreams are the jumping-off point for I Dream of Singapore, it was not a direct reference to films such as A Land Imagined, a 2018 film noir about the disappearance of a Chinese migrant worker from a construction site in the city state.

“It’s a coincidence that Singaporean filmmakers are increasingly making films about the same subject,” he says. “I guess these are common Singapore topics and they are always on our minds as Singaporeans.”

Since the turn of the millennium, filmmakers from the Southeast Asian nation have turned their focus on the Singaporean experience. Colin Goh and Woo Yen Yen’s Singapore Dreaming (2006), for example, is the story of a local working-class family that conscientiously buys lottery tickets in their desperation to realise the “Singapore Dream” of the 5Cs: cash, credit card, condominium, country club membership and car.

Tan Pin Pin’s quirky documentary Singapore GaGa (2005) follows citizens in various strata of society – vendors, musicians, teachers – trying to survive in a country that is rapidly modernising.

Jack Neo, who made movies including I Not Stupid (2002) and Homerun (2003), which resonate greatly with locals, is another home-grown director who often takes a sympathetic look at the average Singaporean trying to keep up with the Joneses, often producing bittersweet results.

The filmmakers from the early 2000s opened the eyes of cinema-goers to the plight of rank-and-file citizens. In more recent years, a new generation of directors including Lei, Anthony Chen (Ilo Ilo, 2013) and Yeo Siew Hua (A Land Imagined, 2018), have asked new questions on the big screen. They have drawn attention to how the dreams of elite Singaporeans, as portrayed in the Hollywood blockbuster romantic comedy Crazy Rich Asians (2018), are built on the aspirations of migrant workers.

The social realism depicted in these films has not only earned accolades internationally, but exposes how the reality of life in competitive Singapore affects every rank and class, foreign or local, with some feeling the pain more than others.

Low-income workers said they were abused and were painfully aware of the gap between them and the privileged classes in a 2018 survey conducted by Dr Janil Puthucheary, chairman of OnePeople.sg – a national body promoting racial harmony in the city state – with Singapore-based news network CNA.

According to a February 2020 survey by lpsos, a global market research firm, nearly four in five of 913 Singaporean respondents aged 18 to 64 agreed that the nation’s economy is rigged to give the rich and powerful an advantage.

For the migrant workers steadily streaming into Singapore with their own idea of the Singapore dream, the predicament is as unpalatable as it is for locals, and even more difficult to stomach.

Ethan Guo, general manager of TWC2, says it is almost impossible for migrant workers to get fair treatment, which creates the perception that the rich and well-connected always get their way while the poorer or the less socially mobile never do.

“In general, living in Singapore is hard because there’s very little room for sympathy, or [any] sympathy … built into the system,” says Guo.

Through filmmaker Lei’s lens, the audience is given an insight into the bureaucratic barricades that migrant workers have to overcome, as well as the loneliness and homesickness that permeates their daily lives. “Waiting at the shelter is really just what they do,” says the director. “Because of language and cultural barriers, they don’t have many Singaporean friends except fellow Bangladeshi roommates.”

This alienation is also apparent in Yeo’s A Land Imagined, which won the Golden Leopard Award at the 71st Locarno Festival in Switzerland, where the stark despair of the “insignificant” foreign worker is evident throughout.

“There haven’t been many films made about the migrant experience in Singapore, which I find very strange since a quarter of the demographic living in Singapore is migrant,” the director says. “The few stories that are told about them focus on their work and function in society.

“I had hoped to focus on their lives outside these convenient categories of impoverished foreign labourers, try to show the humanity we share in common, and also their dreams.”

In contrast to the migrant worker in A Land Imagined trying to find his way out of a desolate and godforsaken Singapore landscape, Lei’s I Dream of Singapore captures the country’s Marina Bay Sands and Gardens by the Bay looming in the background as emblems of the aspirations that took root in Feroz’s mind.

In the end, Singapore did not fit the picture he envisioned. Now back in Bangladesh, helping his ailing father with farm work, Feroz says he is happy to have had the chance to live in Singapore.

“I like that Singapore is neat, clean and has good food,” he says. “But when I was working there it was difficult. My boss always pushed us to be faster; we couldn’t even rest for three minutes.”

Lei uses Feroz’s viewpoint as a migrant to push his audience to see Singapore in a new light. He also seeks to explore universal issues such as social inequality in a Singaporean context.

Currently working as editor and cinematographer on a new documentary about transgender phobia in the state, Lei will be looking at the subject with a sympathetic eye. “I’ll be working with a Singaporean transgender director,” he says.

Yeo is also trying to tell stories that he cares about; some of them, he says, will “inevitably deal with the social contexts I inhabit”.

There haven’t been many films made about the migrant experience in Singapore, which I find very strange since a quarter of the demographic living in Singapore is migrant. The few stories that are told about them focus on their work and function in society

Yeo is developing a feature film that looks at how people’s existence is tied to image-making, and set against the backdrop of a high-surveillance city state.

“I think the reality is that we are all trying to realise our own separate versions of our imagined lands and, naturally, those who are more privileged get to realise it more,” says Yeo. “But I’m curious: does a place like Singapore have the will and capacity to include the diverse imaginations it has within itself? What would this collective imagination look like? I’m excited to know.”