Hong Kong martial arts cinema: how a golden age of wuxia movies began with 1967 classic film One-Armed Swordsman

- One of the most influential Hong Kong films ever made, One-Armed Swordsman modernised the wuxia genre with its release in the late 1960s

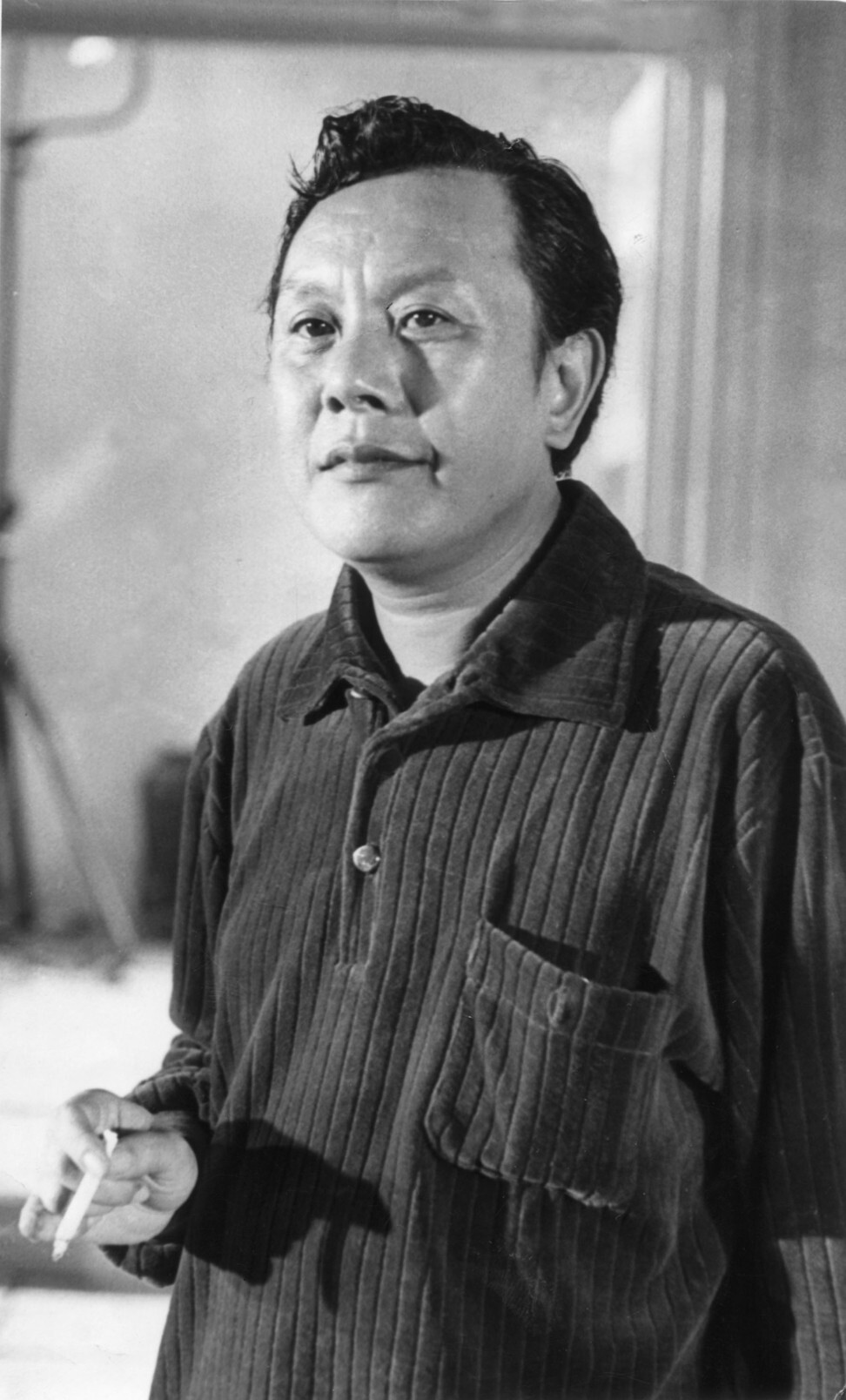

- Director Chang Cheh was an advocate of taking cues from international films like the James Bond series and using modern movie-making techniques

Released in 1967, One-Armed Swordsman is one of the most influential Hong Kong films ever made. Along with King Hu’s Come Drink with Me, which debuted a year earlier, it launched the new wave of wuxia films which modernised the genre in the late 1960s.

Shaw subsequently enjoyed a golden age of wuxia films, which was followed by an equally successful wave of kung fu movies in the early 1970s.

Box-office success is always a hit-and-miss affair but, as film historian Law Kar pointed out in his essay The Origin and Development of Shaw’s Colour Wuxia Century, One-Armed Swordsman was part of a concerted effort by Shaw to bring Hong Kong martial arts films into line with Hollywood action movies and sword-fighting films from Japan.

The action in wuxia films of the 1950s and early 1960s, which used static camera shots and basic editing techniques, looked staged and unrealistic. Law quotes a 1965 issue of Shaw’s magazine Southern Screen which detailed the company’s plans to change that.

“The production of knight-errant [wuxia] adventure films is not new to the Chinese motion picture industry, though the Shaw venture may be termed a progressive movement in that it breaks with conventional ‘stagy’ shooting methods and introduces new techniques to attain a higher level of realism, particularly in the fight sequences,” the magazine stated.

After introducing a few Shaw contract directors, including Chang Cheh, the magazine prophetically noted that: “An action scene is in the making!”

Chang, who had taken a job at Shaw as a script supervisor, suggested that Shaw should take cues from contemporary international action films – notably the James Bond films – and use modern movie-making techniques to update its action films.

Come Drink with Me was the first film to reap the rewards of the strategy.

Hong Kong martial arts cinema: everything you need to know

Chang made three films – Tiger Boy, The Magnificent Trio and The Assassin – before he scored a hit with One-Armed Swordsman.

Co-scripted – like many of Chang’s films – with Ni Kuang, a well-known martial arts and science-fiction novelist, One-Armed Swordsman tells the story of Fang, a maimed fighter who overcomes his disability through willpower and training.

When the young Fang’s father is killed while defending the master of a sword-fighting school from bandits, the master promises to raise and train the boy.

Fang (Wang Yu) is a complex character who is aloof and honourable. He is cruelly teased by the master’s daughter, Qi Pei (Violet Pang Ying-zi), who chops off his arm in a fit of pique. Horribly injured, Fang leaves the school and is taken in by the loving Xiao (Lisa Chiao Chiao).

Meanwhile, a group of martial artists led by the master’s sworn enemy Long Armed Devil (Yang Chi-ching) begins to murder the school’s students by using a new weapon – a grip which can trap a sword like a vice. Although Fang has made a new life with Xiao, he develops a new technique to beat the sword grip and returns to save his former master.

The editing and camerawork were polished and highly cinematic, and imbued the fights with a sense of realism that was new to martial arts films.

“Martial arts films served as a convenient conduit for youthful restlessness, where anger, rebelliousness, discontent and violent urges could be discharged on the screen as entertainment,” Sek Kei writes.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre.