How iconic director John Woo reinvented action movies in Hong Kong and Hollywood

- Mixing spectacular set pieces with sentiment in films such as The Killer and Hard Boiled, Woo started tropes now synonymous with the action genre

- His career has come full circle with his latest film Manhunt, featuring his patented slow-motion, multi-gun action – and, of course, his trusty doves

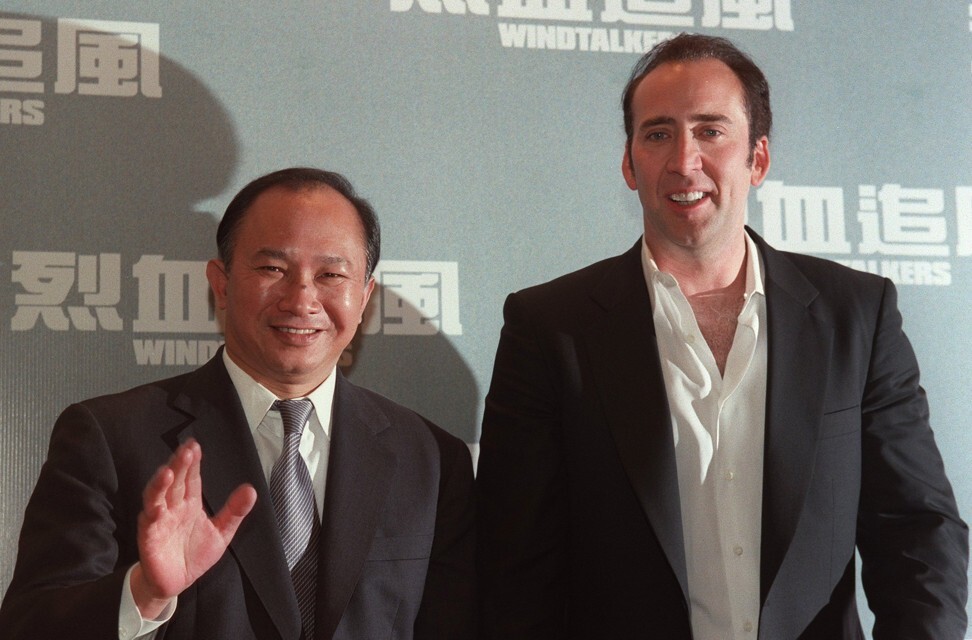

Director John Woo, who turns 74 on Friday, should be considered the godfather of the modern action movie.

Mixing spectacular set pieces with sentiment in films such as A Better Tomorrow (1986), The Killer (1989) and Hard Boiled (1992), he started tropes now synonymous with the genre. These include slow-motion fight scenes, Mexican stand-offs and characters firing multiple guns at the same time. The repeated use of doves, however, is all his own.

Born in Guangzhou in 1946, Woo grew up in Hong Kong after his family fled persecution under Mao Zedong. “As a kid, I always felt like I lived in hell – the slums of Hong Kong were horrible,” he told Venice Magazine. “I always had this dream of living in a better place, a place with no crime and violence … and I could only find that dream in the movies.”

Since then Woo has depicted more than his fair share of crime and violence on screen, with a career that mimics the three-act structure of a typical Hollywood movie: the rise, the fall, then the triumphant return.

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Woo worked his way up through the Hong Kong film industry, graduating to director with 1974’s The Young Dragons, which featured show-stopping action scenes and fight choreography by Jackie Chan. But it was in the 1980s he found his true calling: as the main exponent of the so-called “heroic bloodshed” genre.

Even if you do not know the term, you know the type. Heroic bloodshed films feature cops and criminals who are really two different sides of the same coin; “gun fu” fights combining martial arts with close-quarter firearm action; and a deep seam of emotionality that belies the characters’ nonchalance.

Five great long films that’ll really kill lockdown time

Woo’s first effort was A Better Tomorrow, which pitted triad member Sung Tse-Ho (Ti Lung) against his cop brother Kit (Leslie Cheung), while best friend Mark Lee (Chow Yun-fat) looked on, looking cool.

It broke Hong Kong box office records and was followed by The Killer , in which Chow was promoted to top billing as a hitman doing one final job to save the eyesight of a singer (Sally Yeh). This was also the first film to feature Woo’s signature doves – a nod to his Christian beliefs.

If there is a single image that best exemplifies the genre, it’s the DVD cover of Hard Boiled, which shows Chow Yun-fat in police uniform with a shotgun in one hand, a baby in the other and a bandage above one eye. The film also contains a staggering two-minute-42-second shot that shows Chow and Tony Leung Chiu-wai shooting their way through several floors of a besieged hospital.

“Every action scene I make, the whole scene is all in my head,” Woo said. “I know exactly what I’m doing and what I want. It’s choreographed all in my head already before we start shooting.”

Heroic bloodshed was pure cinema with no need for dialogue or exposition, so it was no wonder that it crossed borders so easily, arriving in Hollywood via the work of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez. Woo followed soon after.

The second act of Woo’s career should have been glorious, but having invited him to the party, Hollywood did not quite know what to do with him. So-so action films Hard Target (1993) and Broken Arrow (1996) brought bigger budgets and bigger stars such as Christian Slater and John Travolta, but felt compromised and cookie-cutter compared to Woo’s Hong Kong output.

Indeed, the only Hollywood film of Woo’s that really delivers is Face/Off (1997), a ludicrously pumped-up sci-fi action film that starred Travolta and Nicolas Cage as a cop and crook who swap identities by face transplant. Cue speedboat chases, Greek mythology references, and much big-chinned, bug-eyed overacting. It could have been even more ridiculous – Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger were originally lined up to star.

“The script was exactly what I like to do with two very different characters, who also have something in common,” Woo said. “There’s no real good guy or bad guy in my films.”

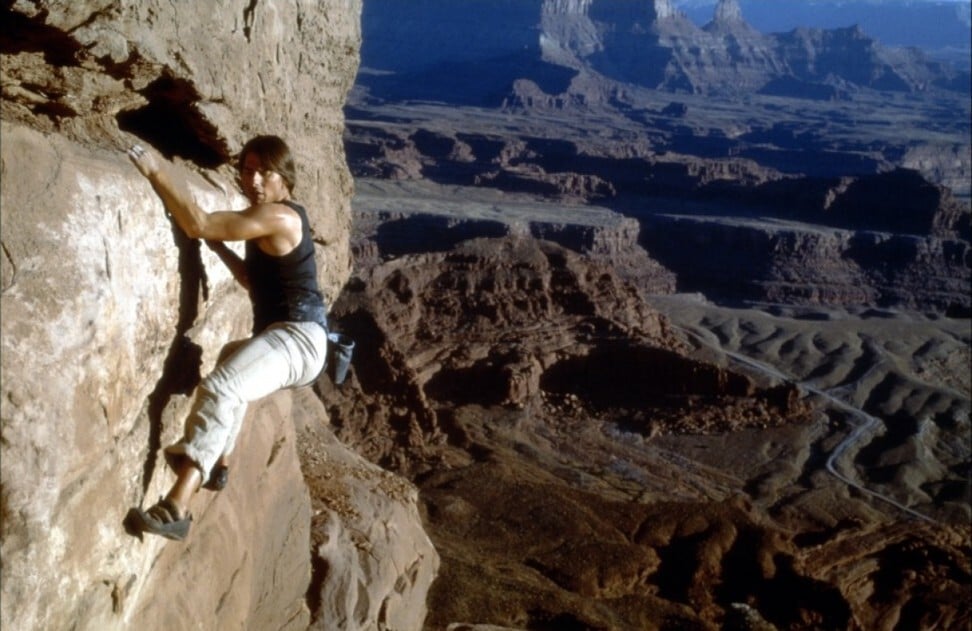

Mission Impossible 2 (2000) should have consolidated Woo’s status in Hollywood, but instead it was cut to pieces by a confused studio and plays like a manic music video. Following the earnest Windtalkers (2002) and the awful Paycheck (2003), he beat a strategic retreat to Asia, but all was not lost.

“After I made Paycheck I couldn’t get any good scripts,” he told Time Out. “And making a movie in China is much more simple. I just walk into the studio and tell them: ‘I would like to make a movie called Red Cliff,’ and they say, ‘OK, it’s done!’”

Indeed, Red Cliff (2008), a two-part historical war film, marked a late-flowering return to form for Woo, with Variety calling it “one of the great Chinese costume epics of all time”. Also split into two parts, The Crossing (2014) was dubbed “China’s Titanic”, and dealt with the sinking of the Chinese steamer Taiping in 1949.

With his latest film, the exuberant thriller Manhunt (2017), Woo’s career has come full circle. Featuring plenty of the director’s patented slow-motion, multi-gun action – and, of course, those trusty doves – it shows us that, despite being in his seventies, the godfather has still got it.

In this monthly feature series exploring Asia’s impact on international cinema, we examine how the continent’s directors have fared in Hollywood, whether its most popular films survived the remake process – and at what cost.