The good, the bad and the ugly: Western-influenced martial arts films of the 1960s

- Westerns were a prominent genre in the 1950s and ’60s, and had a big effect on filmmakers around the world

- The genre’s influences can be seen in two Shaw Brothers Hong Kong martial arts films by Chang Cheh: Have Sword, Will Travel and The Wandering Swordsman

Martial arts films are often compared with Hollywood Westerns, as both types of film strongly reflect the culture of the places that invented them. Westerns, in general, reflect America’s focus on rugged individualism, whereas martial arts films often focus on the activities of groups working together for the common good, for instance.

Considering their cultural differences, it’s interesting to note that Westerns, which were the predominant international genre of the 1950s and early ’60s, had an influence on some martial arts films.

Hong Kong martial arts films did not develop in a vacuum, and were influenced by Japanese sword fighting films, James Bond movies, and the “spaghetti Westerns” of Sergio Leone in the 1960s. The Shaw brothers screened all kinds of films daily in their Clear Water Bay offices to try to spot new trends and techniques.

Two Shaw Brothers films by Chang Cheh, Have Sword, Will Travel (1969) and minor offering The Wandering Swordsman (1970), seem to be attempts by the director and his regular scriptwriter, Ni Kuang, to make a wuxia film in a Western style and setting. Both movies pay greater homage to mainstream Westerns by directors like John Ford and John Sturges than to Leone’s violent spaghetti Westerns.

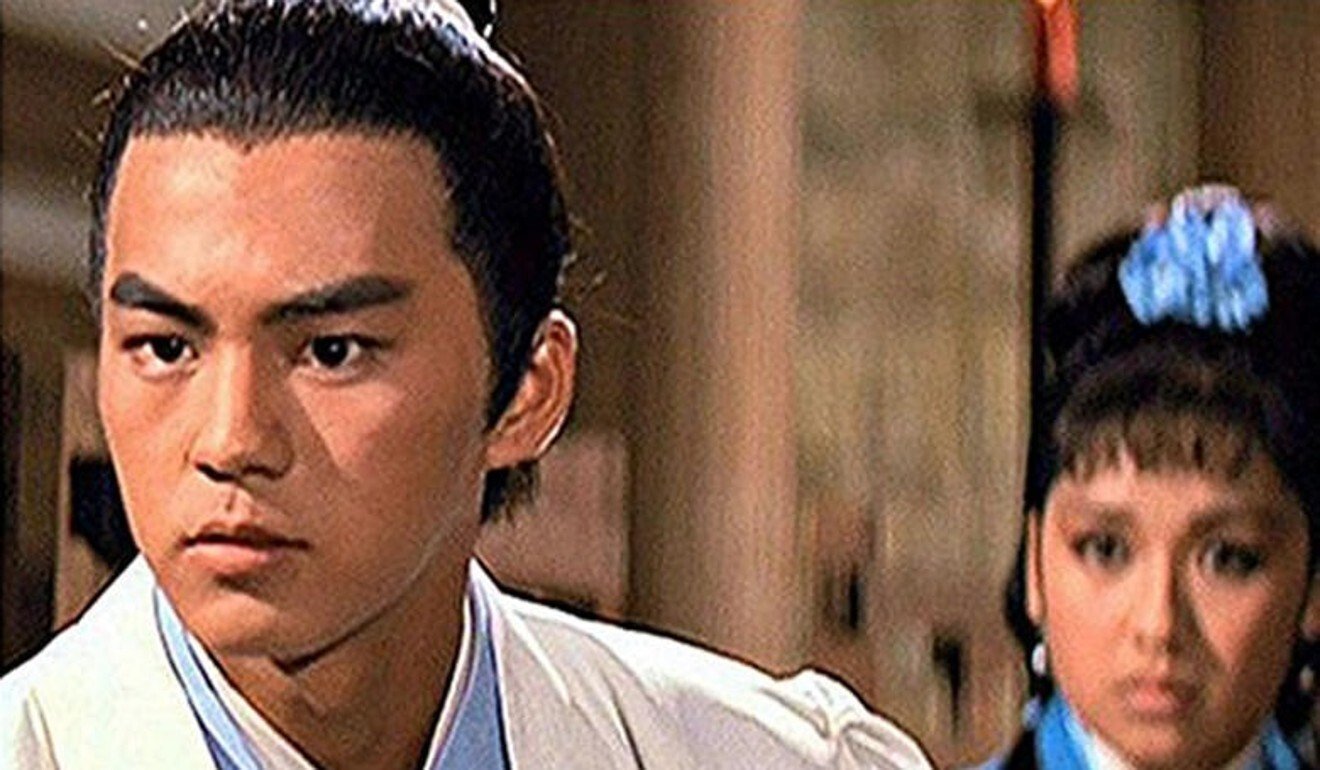

The two films feature skilled horsemen and horsewomen who love and care for their horses – martial arts heroes usually walk, leap, or fly – and towns which reflect the dusty settlements found in many Westerns. The heroes, played by David Chiang Da-wei in both movies, also take on some of the characteristics of Western characters.

Have Sword, Will Travel, which is the superior of the two films, features Chiang as lone horseman Lo Yi, who joins with a village’s security bureau to defend a consignment of government money from an expert gang of thieves.

Lo Yi, who is a petulant and angst-ridden youth, joins with the bureau not out of a sense of justice or duty but because he is besotted with Yun Piao-piao (Chang Cheh regular Li Ching), who is to be married to the bureau’s jealous master swordsman, Siang (Ti Lung). The bloody finale, which features a showdown in a pagoda, sees Lo Yi saving Siang from death at Yun’s request, even though he realises he will die himself if he helps his romantic rival.

Chang Cheh wears his Western influences on his sleeve. Like any good cowboy, Lo Yi loves his horse – he often talks to it, and he is upset when he has to sell it to make ends meet. (The horse is sad, too, and tries to follow him when he leaves.) Horsemanship is heavily featured throughout.

Explainer | Hong Kong martial arts cinema: everything you need to know

Like many a Western hero, Lo Yi is a drifter who says he is not from anywhere in particular, and has spent his life alone, travelling far and wide across China. As with a gunslinger, he is not bound by a code of honour so much as a general sense of right or wrong, and he is motivated by emotions like love, pride and jealousy, rather than the strict social obligations of martial arts heroes.

The Western elements come as no surprise, as the English title of the film, Have Sword, Will Travel, is a pun on a hit American television Western from the 1950s called Have Gun – Will Travel. The film’s Chinese title is The Bodyguard.

The series featured Richard Boone as a black-clad gunslinger who travelled around the Wild West righting wrongs wherever he found them. Aside from the name and the overall idea, the film and the TV series have little in common.

The Wandering Swordsman traded in similar themes, although they were shoddily expressed. The film is not directly connected to Have Sword, Will Travel although the story is also set near the city Luoyang, in Henan province.

This time, Chiang plays a sword fighter known only as the Wandering Swordsman, possibly inspired by Clint Eastwood’s character in Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, who was known as “the man with no name”.

The Wandering Swordsman rescues fellow swordfighter Jiang Ning (Lily Li Li, Shaw Brothers “Queen of martial arts”) from a gang member and immediately falls in love with her. Unbeknown to the Swordsman, Jiang is working for a security bureau which is trying to avoid being robbed by the Flying Robbers gang.

A series of unlikely events see the Swordsman tricked into helping the gang rob and murder the security bureau, which he believes to be a gang of criminals, as they try to transport the valuables. Jiang, who was absent from the massacre, tells the Swordsman what he has done, and to prove that he was tricked, he returns to the Flying Robbers’ camp and attempts to wipe them out and retrieve the treasure on his own

Chiang’s performance is misjudged – he plays the titular swordsman as an overly merry character who is always grinning and, confusingly, giving away his money. If Chang Cheh is trying to construct a typically individualistic and proactive Western hero with the Wandering Swordsman, he has failed badly, as critic Jerry Liu has noted in his essay Chang Cheh: Aesthetics = Ideology?

“The heroic individual blindly submits to the cycle of cause and effect while exercising little control over his own actions … The extreme passivity and mindlessness of Chang’s heroes is typified by You Xia’er [The Wandering Knight] whose actions can be read as a series of automatic responses to the situations in which he finds himself,” Liu writes.

But the milieu of the film is fascinating due to the many Western references. The scrappy streets of the town, which are muddied by horse hooves, and the crowds of people hurrying this way and that, would not be out of place in a John Ford Western. Chang has even included hitching posts for riders to tie their horses to.

A scene in a gambling den, in which the Swordsman uses loaded dice to win, could very easily take place in a Western saloon, perhaps featuring card sharps. Even the Swordsman’s choice of weapon – two short swords carried on his hips – reminds of the gunslinger’s twin six-guns.

There is also a noticeable reference to Westerns in a trick employed by the Swordsman which uses three horses to cover his tracks, and a “fantasy scene” near the end of the film even has him prancing on his horse like the Western hero the Lone Ranger.

By contrast, martial arts films came to America too late to influence Westerns. The genre didn’t become widely known in the US until the early 1970s, and Westerns had gone into decline at the end of the 1960s.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre. Read our comprehensive explainer here.