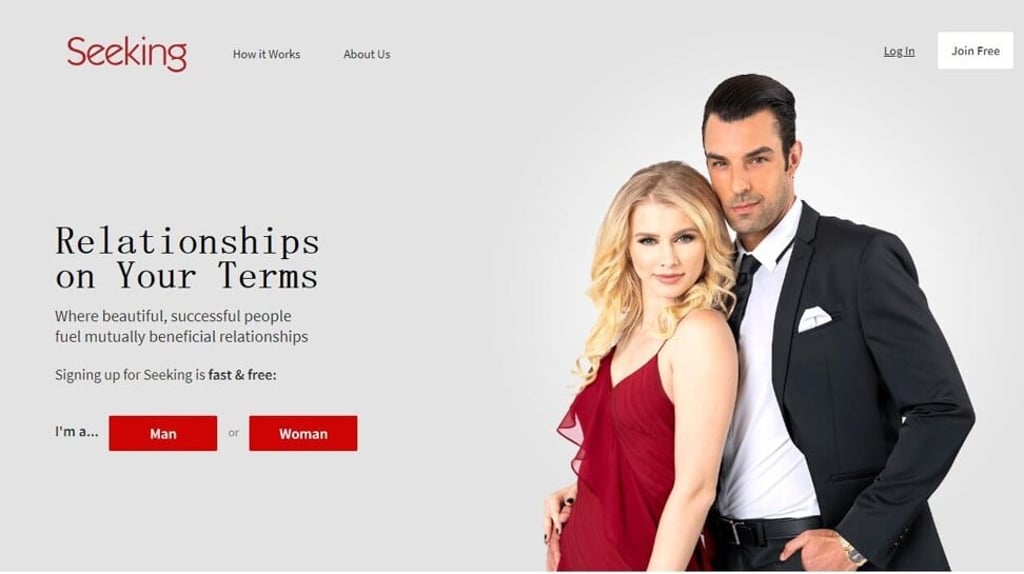

Fake ‘sugar daddy’ scams target people left financially insecure by Covid-19 pandemic

- The health crisis has seen more lonely people registering to be ‘sugar daddies’ and more financially vulnerable ones signing up to serve as ‘sugar babies’

- Scammers have been quick to take advantage, with fake sugar daddies preying on the unwary through a con known as advance-fee fraud or the ‘Nigerian prince’ scam

The man who scammed Elizabeth Mirah seemed legitimate. A stranger contacted the 28-year-old Massachusetts woman on the fetish social network FetLife, offering her money. He identified himself as a “sugar daddy” – typically an older man who pays younger “sugar babies” for dates, companionship and sometimes more.

“We went back and forth and he seemed like a legitimate person,” Mirah says. When he asked for her bank account details, she became suspicious. But she was about to lose her job as a cafeteria manager and thought: “I need the money, what’s the worst that could happen?”

To her surprise, two cheques of US$1,500 appeared in her account. When the mystery benefactor asked her to send US$500 to his nephew on a mobile payment platform, she agreed. She questioned why he couldn’t do it himself, but felt she owed the stranger a favour. She continued to send money. Three days later, the US$3,000 had disappeared. The cheques had bounced. It was too late. By then, Mirah had already sent US$1,000.

The data shows genuine sugar daddies are relatively rare: only 16 per cent of members, who are background-checked, are registered as sugar daddies.