The director who revolutionised martial arts movies by making his male characters warriors instead of weaklings

- Chang Cheh modernised wuxia films in the 1960s by making men, rather than women, the action heroes and adding violence and bloodshed to screenplays

- The male bonding and transcendental violence in later John Woo films can be traced back to Chang’s work; Woo was one of many directors influenced by his films

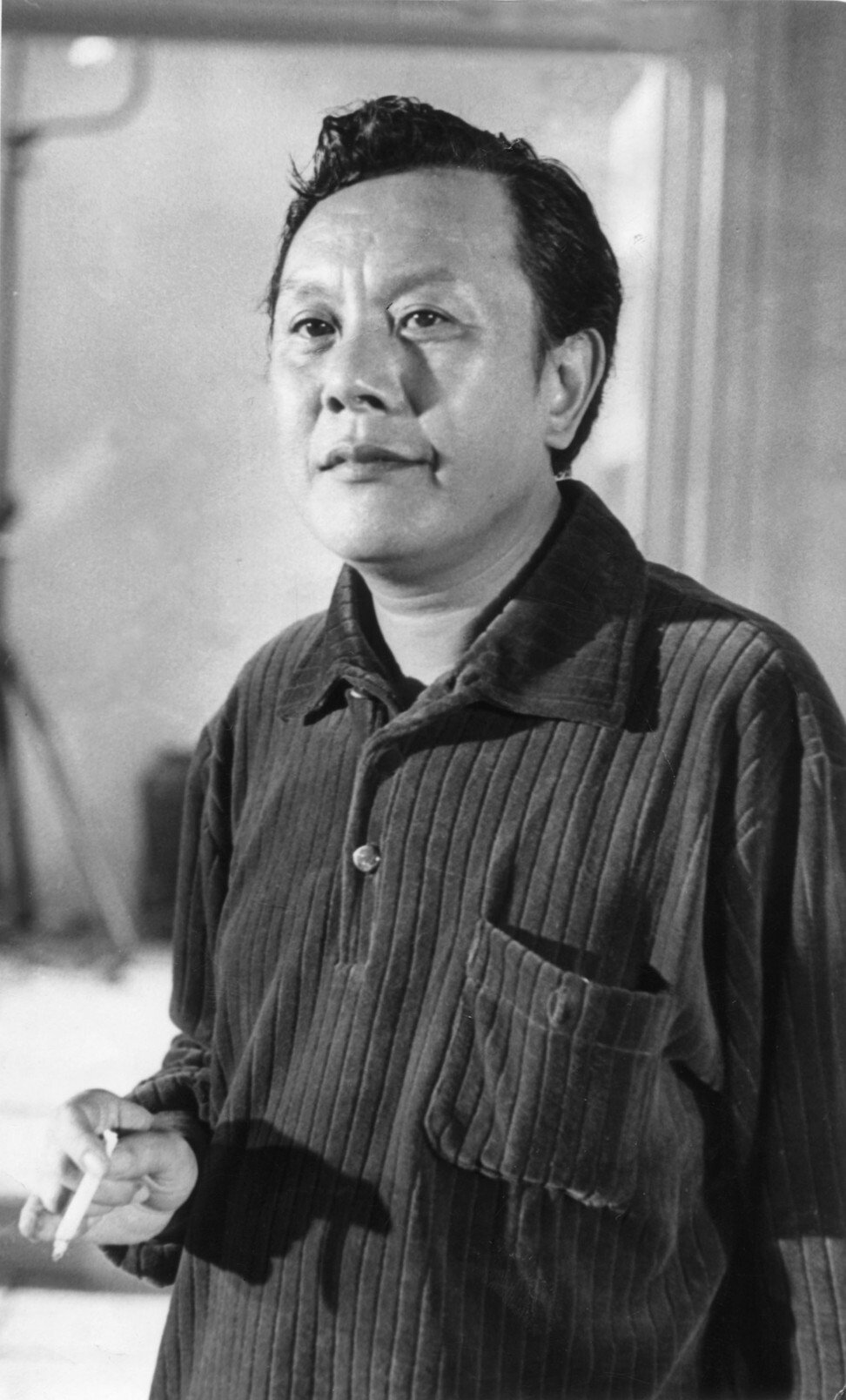

Chang Cheh is one of the most discussed filmmakers in Hong Kong, although abroad, he is only known to followers of martial arts films.

The prolific Chang directed over 90 films before his death, at age 79, in 2002. Although his output is patchy, he made some classics that became landmarks of Hong Kong cinema.

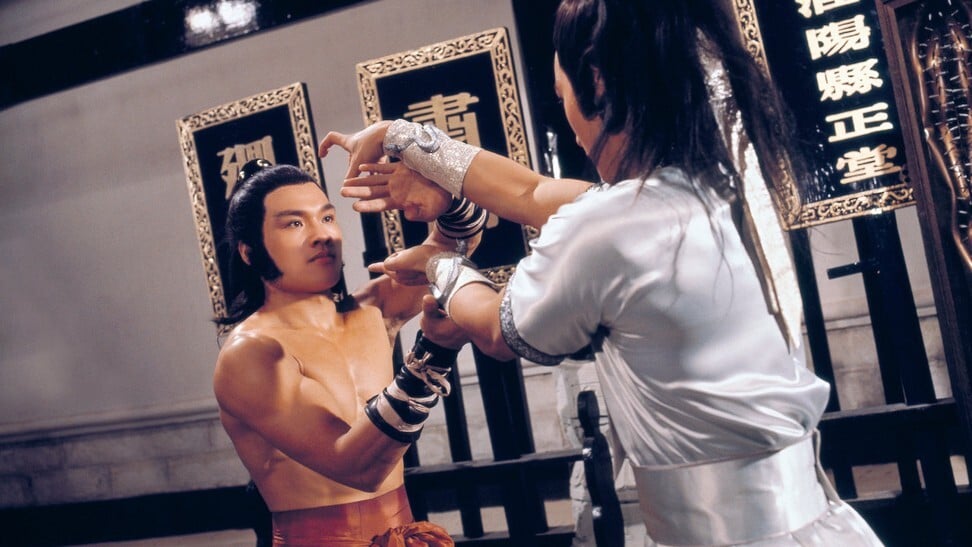

The director brought the wuxia genre up to date by adding violence and gore, and by shooting and editing the action sequences with more modern techniques.

He also changed the gender balance of Hong Kong films, which in the 1950s and 1960s had favoured female heroes, with the male characters often weak.

Chang brought macho heroes to the fore, and made them rebellious and angry to suit the tenor of the times. When the wuxia genre faded in the 1970s, Chang started making kung fu films, and saw similar success there.

Chang was also a star-maker and guided the careers of Jimmy Wang Yu, David Chiang Da-wei, and Alexander Fu Sheng. John Woo worked as assistant director on some of Chang’s films in the 1970s, and the male bonding and transcendental violence of Woo’s later films can be traced back to Chang.

Hong Kong martial arts cinema: everything you need to know

Many actors, directors and film critics have spoken about Chang’s extensive body of work down the years.

Sek Kei, leading Hong Kong film critic, to the SCMP’s Richard James Havis:

“The aesthetics of violence in his films exerted tremendous influence over the cinema of Hong Kong, and other Chinese-speaking regions, until the 1990s.

Actor David Chiang, speaking in a documentary by Severin Films:

“I learned so much from Chang Cheh. I learned how to be an actor and how to be a director.

“There is passion in his swordsman films, there is feeling in them … there is a romance to Chang Cheh’s swordsman films that I don’t see in the films of other directors. I am still learning from those films today.”

John Woo in the introduction to Chang Cheh’s memoirs:

“Chang Cheh was a man of few words and a man of his word. He saved his eloquence for his films and his writings. The structural fluidity of his cinematic images and writings, besides being captivating, exhibit a depth that reveals his true self and character.

“His films – characterised by the pursuit of lofty ideals but never at the expense of ordinary human emotions – extol the martial arts as well as the gallantry spirit. Grand in style and magnificent in presentation, his films leave the audience in cathartic exaltation.”

Sek Kei, film critic, again:

“In the 1950s and 1960s, Hong Kong cinema was dominated by female movie stars, in Mandarin- and Cantonese-language films.

“Chang Cheh was renowned for pioneering the yang gang [staunch masculinity] style which uprooted the foundations of local cinema and established the supremacy of the male action hero for years to come.”

Critic and academic Stephen Teo in his essay The Macho Self-Fashioning of Chang Cheh :

“The characteristics of [Chang’s] male heroic archetype can be summed up in the term ‘yang gang’, which translates as ‘staunch masculinity’: yang denoting the male principle and gang indicating fitness or strength. Basically, it is the Chinese expression of machismo.”

Sek Kei, film critic:

“Though there were male iconic figures in the wuxia and kung fu films of the 1950s and 1960s, like Wong Fei-hung, they usually upheld traditional Confucian patriarchal norms and values. By comparison, the male protagonists in Chang’s films have a sense of youthfulness and rebelliousness and submit to violent urges.”

Critic Tian Yan from his 1984 essay The Fallen Idol in Retrospect :

“Since his early days as director, Chang Cheh has been criticised for his unrefined technique and his sloppy narrative structure. He declares in an interview: ‘I don’t ever plan the shots … and I don’t believe in planning them either.’

“About the authenticity of costume and hairstyles in period drama, he says; ‘I ignore research totally … it is deliberate on my part … in my opinion, one should do what one pleases.’ He also admits to his flaws: ‘I am not a cool and practical planner who works things out in an orderly fashion. This failing results in the inconsistency of my work’.”

King Hu, director, from a 1993 interview in Taiwan:

“Actually he [Chang Cheh] became active in the industry somewhat later than me. When I was making Come Drink With Me, he was making a film about the sale of a weird fish, I believe. The film talked about how a strange fish was caught and then stolen by a young hoodlum. [The film was 1965’s The Butterfly Chalice.]

“It was a huangmei diao film [huangmei diao was a Cantonese-language musical genre]. I remember the film about the fish, because when I was working on Come Drink With Me, I saw him working on that film across the lot at Shaw Brothers.”

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre. Read our comprehensive explainer here.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook