Ups and downs of Naomi ‘SexyCyborg’ Wu, Chinese tech-loving YouTube star who’s more than just breasts and exposed skin

- Wu has almost 1.2 million YouTube subscribers but has been defunded twice, from Patreon and SubscribeStar, leading to huge losses in income

- A ‘high femme’ lesbian with breast implants and a penchant for hot pants, she is often accused of pandering to the male gaze but says her look makes her happy

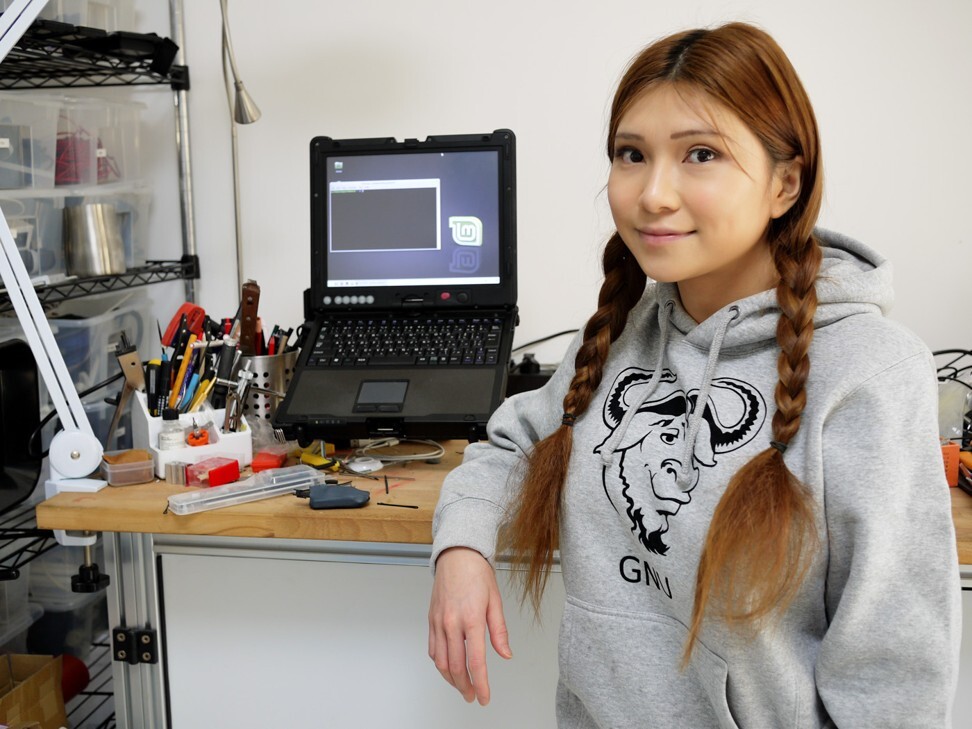

In a rundown villa on the outskirts of Shenzhen sits Naomi “SexyCyborg” Wu’s apartment workshop. Surrounded by a half-dozen 3D printers, two laser cutters and an industrial milling machine, her workstation is something she could only dream about four years ago.

But it’s all been made possible by the success of the English-language videos the 27-year-old shoots for her almost 1.2 million subscribers on YouTube, be it tech reviews, DIY projects or 360-degree immersive videos of her life in Shenzhen, the hi-tech city in China’s southern Guangdong province bordering Hong Kong.

Wu has been defunded twice. Her Patreon account was taken down, and an alternate payment processing site she used, SubscribeStar, ran into some financial hiccups. Mainland Chinese YouTubers have limited income options, so a lack of such platforms meant a major loss of finances.

Despite such ordeals, Wu hasn’t given up. “I’m told I’m a bit ferocious, although people on the wrong end often use less kind terms. My family members are working-class Foshan folk; a bit rough around the edges,” Wu says in an email, referring to another city in Guangdong province.

“I’m no fine lady. I was raised hard, by hard people. Those who come to my city looking to make trouble, they expect Chinese girls to be timid and docile, but as any Chinese will tell you, Guangdong doesn’t make them like that,” says Wu, who has spent most of her life in Shenzhen.

Chinese netizens angry at Lee Hyori’s ‘belittling’ Mao comment

Growing up, she was enthralled by American culture and spent countless hours on YouTube. She studied English passionately, even winning several awards in middle school, and graduated with an English major.

Wu started her YouTube channel in 2016. She was a freelance web developer at the time, having taught herself to code in college for extra income. In 2018, she started earning a modest income entirely through YouTube.

“It’s just me and my camera walking around, and the viewers can see everything – no full production crew, no carefully framed shots, no teleprompters or cue cards,” she says.

As a Chinese YouTuber with a Western audience, there wasn’t a rule book to follow and she had “no way of knowing how this would be viewed by the government”.

In her videos, she showed off the streets of Shenzhen and filmed at pool parties where local women with successful Amazon stores partied in bikinis. “This wasn’t what people thought China was like. And I had no way of knowing if my China, my home, my life, was an acceptable China to show the world,” Wu says.

As her social media platforms grew, so did her profile as a Chinese “maker”, a term for tech enthusiasts who create or build things.

Eventually, Wu caught the attention of Dale Dougherty, a leading advocate of the international maker movement. But Dougherty accused Wu of being a fraud, saying in a tweet from November 2017: “Naomi is a persona, not a real person. She is several or many people.”

Despite having some prominent figures to back her up, and eventually receiving an apology from Dougherty, the damage was done.

“To this day, people still repeat the rumour, even though I’ve hundreds of hours of video disproving it,” Wu says. “My authenticity is well established enough at this point that prying into my personal life is just shorthand for attempting to deprive me of agency, so I don’t take kindly to it.”

Dougherty’s accusations stemmed from Reddit conspiracy theories, claiming Wu was married to a white male, and he was the one behind her work.

“I had what we call a ‘contract marriage’ or a fake husband,” Wu says. “This is common in China for the LGBT community. It makes life go smoothly.”

Her contract marriage took place before she was known online as SexyCyborg. But later, as a Chinese YouTuber with strong opinions, a non-traditional appearance and often campaigning for female inclusion at local tech events, having a “white husband” became potentially problematic.

I looked like this long before I went on Western social media. It’s a reflection of my gender identity, but I don’t expect people to know that. I do wish they were a bit kinder in their initial assessment of me

So she kept the marriage and her sexual orientation discreet. “This was my choice and one I was happy with. But that was taken out of my hands when I was outed by Western journalists.”

To rebuild her reputation, Wu agreed to an interview with Vice magazine. A Vice crew flew to Shenzhen and followed her for three days. According to Wu, they agreed in writing to keep certain subjects off-limits, particularly her sexual orientation and her relationship with a woman.

However, Wu felt the agreement was not upheld and that put her at risk. The published story mentioned her relationship, even after Wu’s numerous attempts to dissuade them.

She ran out of options and, in reluctance, fought back by flashing the address of a Vice editor in her video for five seconds. In retaliation, Vice had Patreon terminate her account for violating its guidelines.

Without Patreon, Wu lost all her monthly income. Her channel went on hiatus and she returned to freelancing to make ends meet. She switched to another crowdfunding site, SubscribeStar, but it was soon banned by credit card processors PayPal and Stripe for hosting rightwing activists and pornographers, reasons unrelated to her.

Today, about three-quarters of her income comes from two Chinese sponsors: 3D-printing company Creality3D and electronic parts manufacturer JLCPCB. The rest comes from YouTube ads and viewer donations.

Even with these alternatives, and her restored SubscribeStar account, Wu makes less than a third of what she did on Patreon. Her friends with similar skill sets earn much more, but Wu says her work has been rewarding and interesting.

As a YouTube creator, hitting a million subscribers was quite an accomplishment. Another, she says, was the appearance on Chinese television of the rainbow flag next to the Chinese flag hanging on her wall.

“I’d been warned that sort of symbolism was usually removed. There was no way it [would have] made the final cut without a lot of discussions, but that acceptance means a great deal to me,” she says.

While her flamboyant appearance gave her an initial boost in recognition, Wu says at some point it became counterproductive.

“I looked like this long before I went on Western social media. It’s a reflection of my gender identity, but I don’t expect people to know that. I do wish they were a bit kinder in their initial assessment of me,” she says.

As a “high femme” lesbian, Wu is often accused of pandering to the male gaze, but she remains undeterred. “High femme is what makes me happy, and I’ve got no plans to live any other way.”

In the next few years, Wu hopes to enter manufacturing and open a small factory.

“I’m good at marketing and I have a good feel for what Western consumers want, so I could be successful at that. I’ve spearheaded a few products now so I have some confidence I can do this.”