Explainer | Hayao Miyazaki's movies: why are they so special?

- Miyazaki has captured the hearts of film-goers worldwide and won the best animated film Oscar in 2003 for the spooky and surreal Spirited Away

- The stories he animates may be full of whimsy, but the Japanese genius is a hard taskmaster who sets exacting standards for himself, his peers and studio staff

After Walt Disney, Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki is the best-known animator in the world. Since making his big- screen debut with The Castle of Cagliostro in 1979, films such as 1988’s My Neighbour Totoro – a gentle story about friendly woodland spirits that still stands as his signature piece – have frequently topped the Japanese charts, broken box-office records, and won awards in Japan.

Acclaim from animators in the United States led to a breakthrough in the West around the start of the new millennium, and Miyazaki’s films began to gain international appeal after the US release of the ecologically aware Princess Mononoke in 1999. Miyazaki won the best animated film Oscar in 2003 for the spooky and surreal Spirited Away, which also shared the prestigious Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 2002.

Miyazaki, who was born in Tokyo in 1941, began his career working in television at Toei Animation, but most of his films have been produced by Studio Ghibli, which he founded with his friends and colleagues Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki in 1985. Ghibli halted production in 2014 when Miyazaki announced his retirement, but reopened in 2017 when he decided to go back to work on How Do You Live?, which is currently some three years away from completion.

Miyazaki will receive his first North American museum retrospective when the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is inaugurated in April 2021.

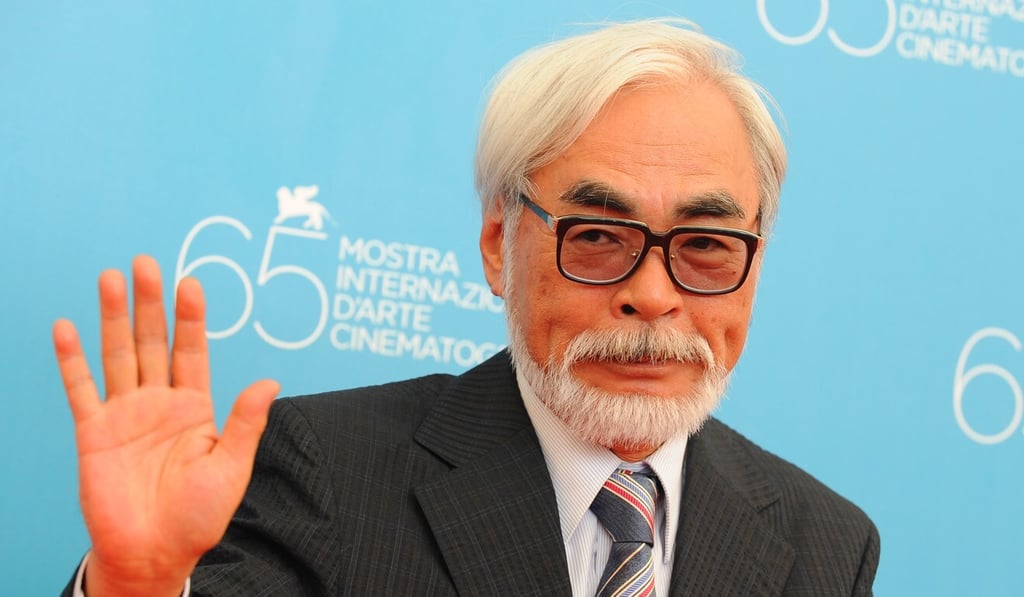

In spite of his avuncular appearance, Miyazaki is known as a hard and sometimes ruthless taskmaster who sets exacting standards for himself, his peers, and his employees.

He is a workaholic who sometimes falls asleep at his desk, and admits he has often neglected his health – and his family – in the pursuit of his art.