How wuxia movies drew on martial arts novels by Louis Cha, Gu Long and Liang Yusheng

- Film directors such as Stephen Chow, Wong Kar-wai, and Tsui Hark mined plots and characters from novelists’ tales of romance, chivalry and combat

- While filmmakers also drew on actual events and historical characters, martial arts novelists were integral to the success of wuxia movies

Martial arts movies did not just spring out of nowhere – they have an intrinsic connection to Chinese culture. The films exist as part of the martial arts subculture, or jiang hu, and often draw on the characters and storylines of well-known martial arts novels or feature real or mythical heroes from the past.

Wuxia movies as a whole draw on the immense body of martial arts novels produced in Greater China, while kung fu films may be based on histories, folk stories, myths, and stories – usually from southern China – that have been shared among the martial arts fraternity.

Martial arts novels tend to be long and episodic, and feature many different characters and intricate, wide-ranging plots and storylines in the manner of the Chinese classic The Water Margin. So filmmakers usually just pick one storyline and one set of characters from a novel and construct a film around these, excising most of the book in the process. (Such novels receive more extensive adaptations as television series.)

Hong Kong martial arts cinema: everything you need to know

Sometimes a book can be so well-known in Hong Kong – such as a work by Cha – that filmmakers assume that viewers already know the story, and consequently skimp on providing any background. This can lead to problems when the film plays in the West, where viewers will probably not have read the original book.

The “wandering knights” of the wuxia novels and films draw on character types developed in ancient Chinese chivalric literature. The earliest is thought to be On the Sword (Shuo Jian Piang), written in the Warring States era (403-221BC).

As writer Liu Damu has pointed out in his extensive essay From Chivalric Literature to Martial Arts Film: “Swordsmen in this book are described as having ‘bristling hair on their temples, dangling hats tightly tied with plain streamers, and gowns that are shorter at the back. Anger shows in their eyes, and they dislike conversation.’ This fearsome image is consonant with that of the martial arts hero in modern wuxia novels and films.”

Other early literary sources include The Biographies of the Wandering Knights-Errant and The Biographies of the Assassins (90BC), romances from the Tang dynasty (618-917AD), and detective stories from the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

There was a surge in the popularity of martial arts novels in China’s Republican era, and some included the fantastique (fantasy) elements beloved of directors like Tsui Hark, such as heroes that were half beast and half man.

It was the rebellious nature of the knights errant and their relentless pursuit of justice that mainly appealed to readers in Republican times, qualities that surfaced in the New Wave martial arts film of late 1960s Hong Kong. Readers could “readily identify themselves with those who opt out of society and rely on their own strength to confront a society whose workings escape them”, Olivia Mok writes in her introduction to Cha’s novel Fox Volant of the Snowy Mountain.

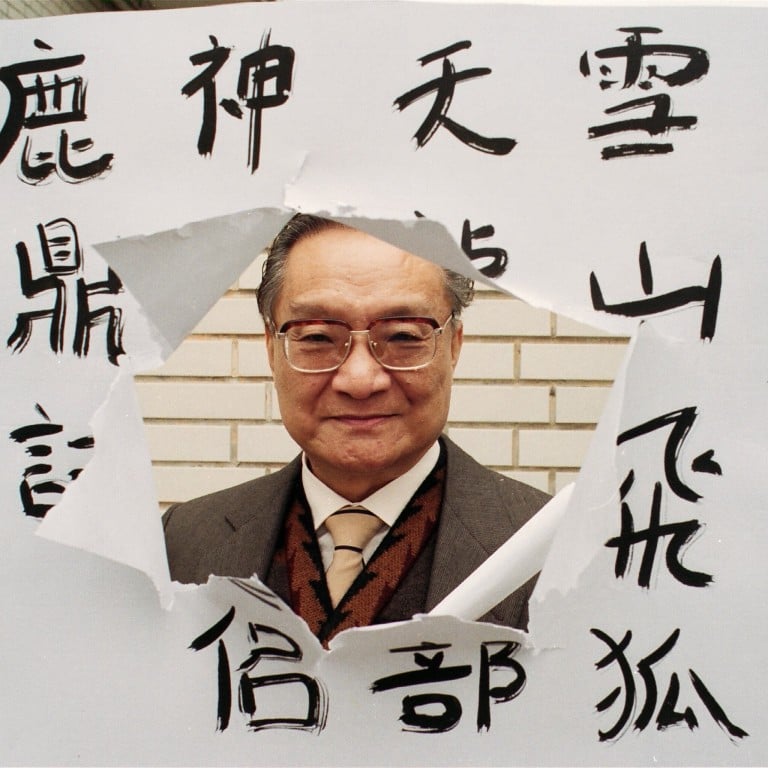

Cha, Hong Kong’s most famous novelist, is the writer best known for movie adaptations of his work. Cha wrote 15 wuxia works, which stretched to 46 volumes.

Films based on Cha’s work include Chang Cheh’s Brave Archer series, Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time, and Jeff Lau’s Eagle Shooting Heroes (all based on The Legend of the Condor Shooting Heroes); Tsui Hark’s Swordsman trilogy (very loosely based on The Proud Smiling Wanderer); and Stephen Chow and Wong Jing’s Royal Tramp films (based on The Deer and the Cauldron).

“In his analysis of Louis Cha’s work, the critic Lin Yiliang has observed that Cha’s imagery and literary style contain the equivalents to cinematic devices such as long, medium and close shots, and sound effects in their articulation of character and action,” writes Liu Damu.

“Although Louis Cha’s work lends itself easily to cinematic adaptation, the novels are nevertheless filled with detail and develop along non-narrative lines … for this reason, the films adapted from Louis Cha’s work are often based on episodes from the novel, rather than complete stories,” writes Liu.

Taiwanese novelist Gu Long became a major writing force in the late 1960s, and 19 of his works were adapted for Shaw Brothers by Chor Yuen, including Killer Clans and The Sentimental Swordsman. Gu introduced to the literature the idea of the lone martial arts hero who operates without worldly ties – something which he saw as a reflection of his own existence.

“I want to be alone,” the novelist once said. “It is only in solitude that I can discover myself. It is only then that I can escape from the contagion of other people.” He was known for intricate plots that often made use of themes of detection.

“Gu Long was a keen observer of human nature,” director Chor Yuen wrote. “His descriptions of fighting scenes may not be as vivid as Louis Cha’s, but his characters, despite being sparsely sketched, came alive when interacting with each other. Gu Long novels were literary romances, the difference being that the characters were skilled in martial arts.”

Liang Yusheng, who began his novels with a poem, invented the idea of the martial arts artist who was also a scholar. Chen wrote 29 martial arts novels, including the 15-book The Wanderer and Mount Heaven Chronicles. Adaptations of his work include The Jade Bow (1966), the precursor to the New Wave wuxia films, and Ronny Yu Yan-tai’s vibrant The Bride with White Hair .

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre. Read our comprehensive explainer here.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook