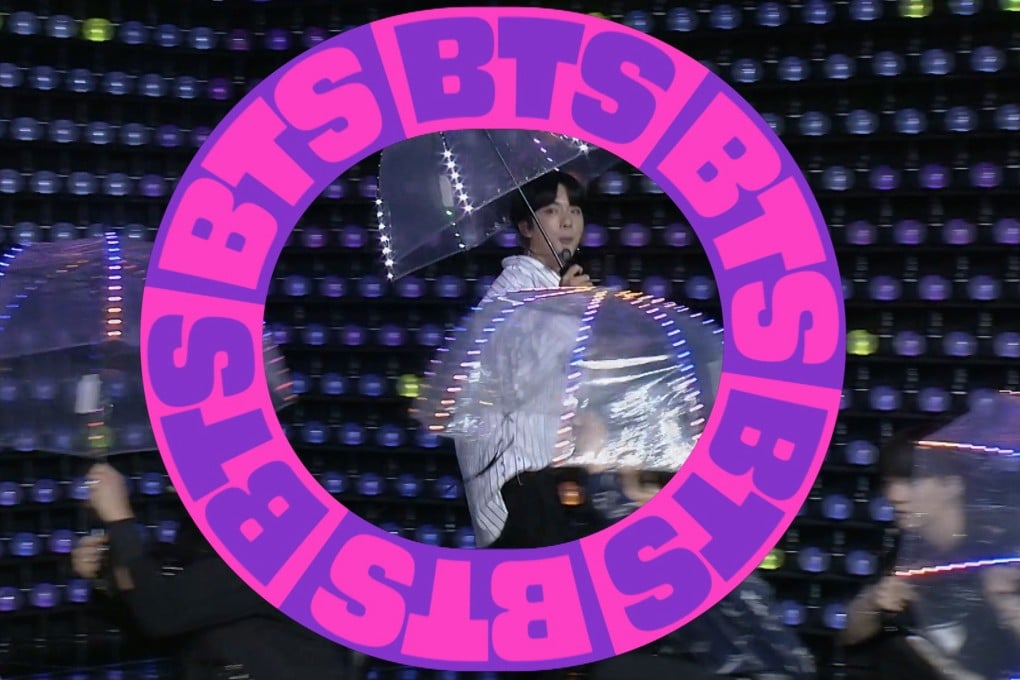

Success of BTS, Nick Cave and Niall Horan online concerts gives music festivals like Glastonbury hope of live-streaming profits

- BTS’s BangBang Con attracted more than 750,000 viewers in 107 countries, generating nearly US$20 million in revenue, with audience engagement a huge priority

- Live-streamed concerts made US$600 million in 2020. Organisers of the Glastonbury festival hope to cash in by staging a virtual festival, Live at Worthy Farm

The coronavirus pandemic has forced virtually all live musical performances onto the internet – and paid-for music live-streams have been so successful that, when and if it finally recedes, a lot of performances are likely to stay online.

Live performance has been the backbone of the music industry since streaming gutted record sales, so musicians, as well as the industry that supports them, have lost most of their income recently.

Concert industry trade publication Pollstar estimated that the global concert industry lost US$9 billion, or 75 per cent of its revenue, in 2020; the world’s biggest promoter, Live Nation, reported a 95 per cent fall in revenue.

Enter paid live-streams. Erykah Badu was probably the first major artist to present one, in March, 2020, but since then an avalanche of others have followed.