Review | Me and the Cult Leader movie review: Japanese documentary follows Tokyo subway gas attack victim and member of the cult responsible across the country

- Atsushi Sakahara, a victim of the 1995 sarin gas attack, documents his meeting with Hiroshi Araki, PR director of what was then known as the Aum Shinrikyo cult

- Anyone unaware of their backgrounds might be forgiven for mistaking this as a reunion between old classmates as they journey to their hometowns

3/5 stars

Me and the Cult Leader is not your typical showdown between bitter rivals. Anyone unaware of Sakahara and Araki’s backgrounds might be forgiven for mistaking this as a reunion between old classmates. They are friendly towards one another, making jokes and small talk, as they journey to both their hometowns.

Inevitably, conversation turns to the horrifying incident that tragically entwined their lives, but even then there is a reluctance to bring it up, let alone relive the details or ruminate on the aftermath.

Araki, who is cripplingly timid and inarticulate, guides the jolly and jocular Sakahara around the modest living quarters he shares with other cult members, before taking him to the small rural village where he shares fond memories of childhood holidays at his grandmother’s home.

They visit the campus of the prestigious university where Araki studied before dropping out to join Aum, renouncing everyone and everything he knew in the process.

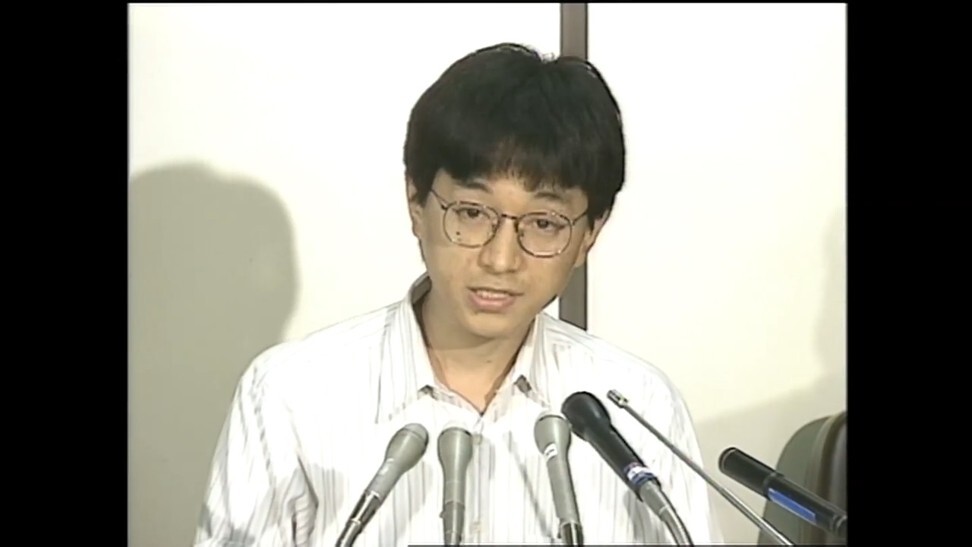

The film builds to a desperately uncomfortable meeting between Araki and Sakahara’s elderly parents, before a public mea culpa at the Kasumigaseki Station, targeted in the 1995 attack, in front of the press. Those who came looking for explanations or apologies are left sorely disappointed.

Where the film succeeds is in portraying a deeply damaged human being who hitched his wagon to a highly dubious organisation and for whom any notion of distancing himself from this last-gasp sanctuary is too horrifying to contemplate. Living with the stigma of being associated with this deadly atrocity is, for Araki, somehow the lesser evil.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook