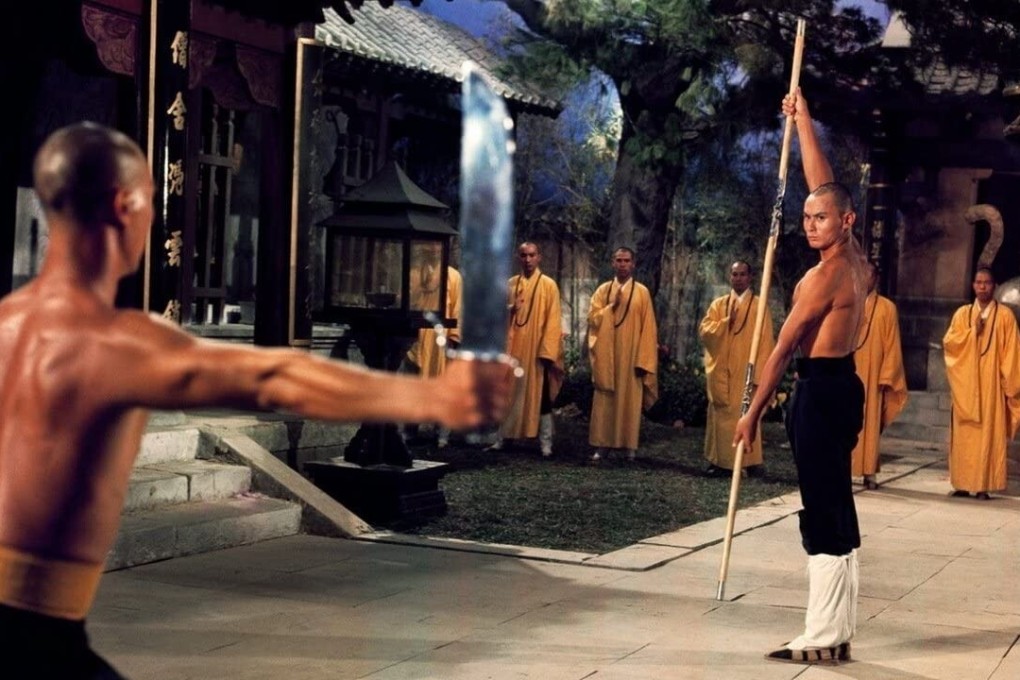

How Gordon Liu became a martial arts superstar thanks to Shaw Brothers movies like Dirty Ho and The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter

- Liu made his name as the bald-headed monk in The 36th Chamber of Shaolin in 1978 and went on to appear in several acclaimed Shaw Brothers movies

- Cast later by Quentin Tarantino in the Kill Bill films, Liu was an elegant fighter who learned kung fu from martial arts choreographer Lau Kar-leung’s father

“He has generally appeared in films of some quality,” a Hong Kong critic wrote in 1981.

Liu came into vogue again during the martial arts boom of the 1990s, taking supporting roles in movies such as Last Hero in China, and yet again in the 2000s when Quentin Tarantino cast him in the two Kill Bill films. Sadly, the affable Liu suffered head trauma when he fell while having a stroke in 2011, and has been in a nursing home ever since.

Martial arts performers fall vaguely into different camps – actors who learn martial arts for their roles, former stuntmen who have picked up martial arts as their careers progressed, those who learn martial arts in Beijing Opera schools, and those who began their careers as martial artists and then moved into acting.