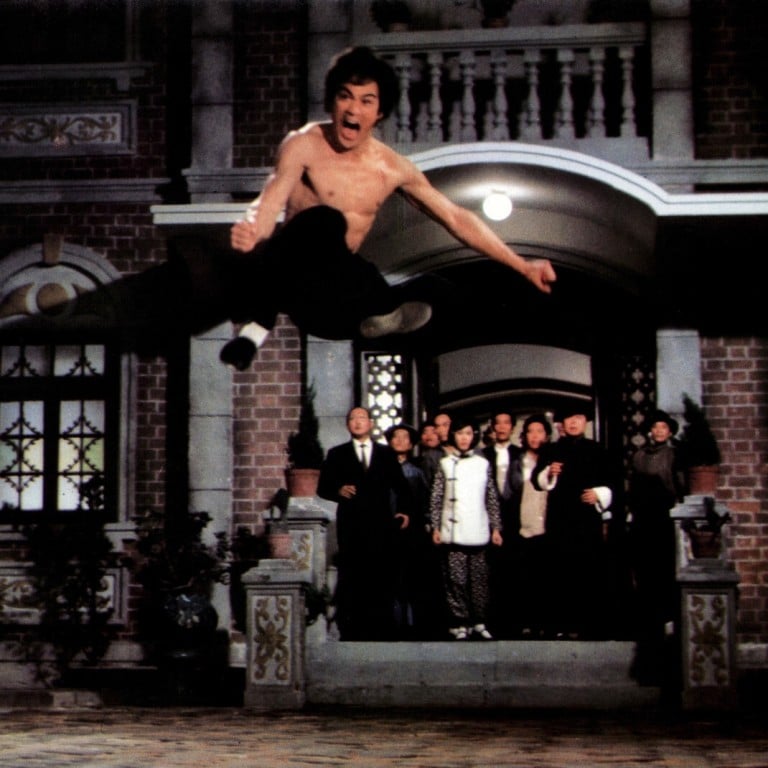

Why African-Americans identified with Bruce Lee and the underdog themes of Fist of Fury and many other Hong Kong martial arts films

- African-Americans loved kung fu films because their themes often reflected their own social and political oppression; some watched them to learn kung fu moves

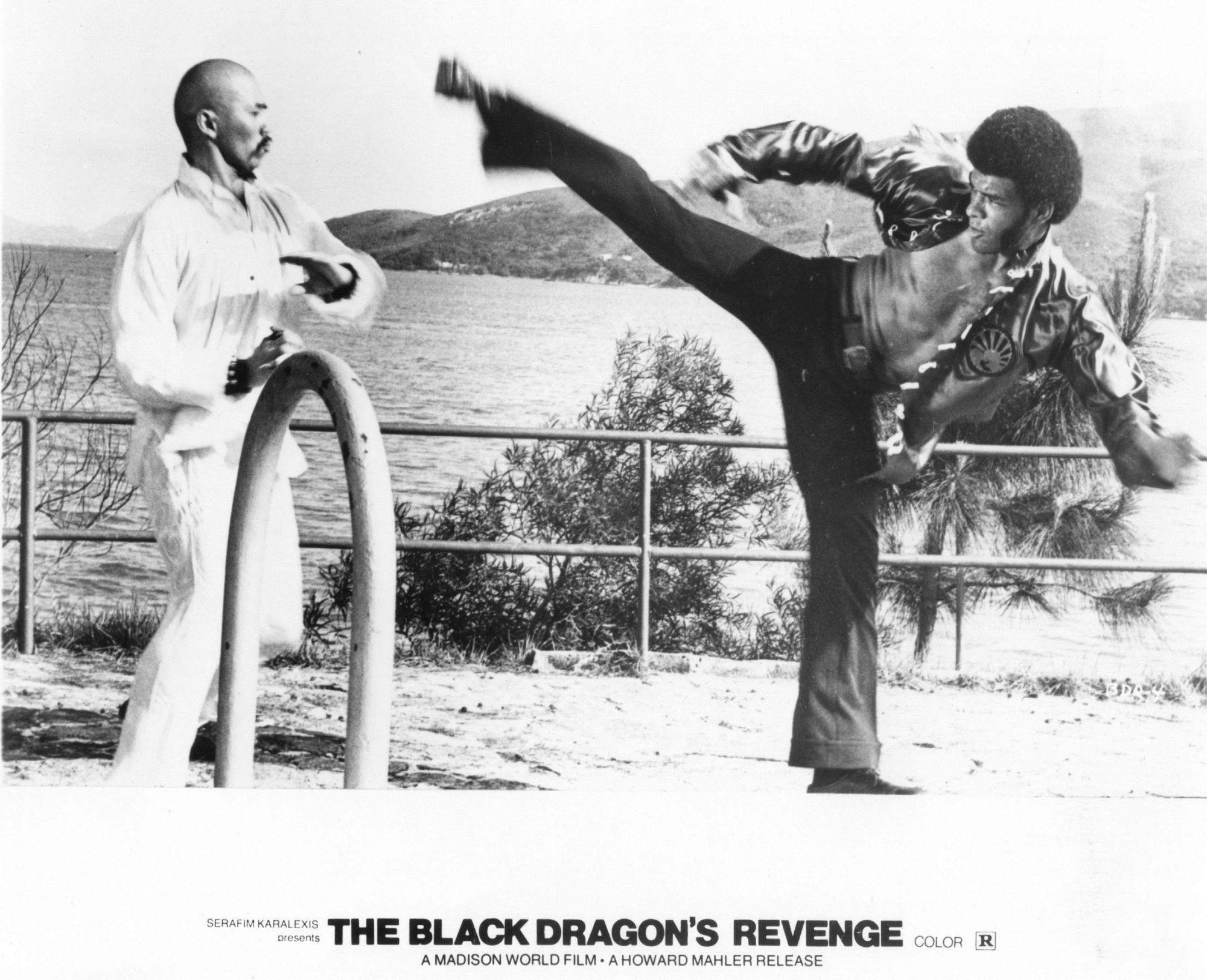

- As well as appreciating the fighting style, their interest spawned ‘Blaxploitation’ crossover films that made stars of black martial arts actors like Jim Kelly

It’s well known that African-Americans spurred the popularity of Hong Kong martial arts films in the United States, as well as the actual practice of martial arts in the country. But what was it that attracted them to the city’s kung fu movies?

The answer is complex, and is tied in to the seismic social and political events that took place in America in the 1960s and 1970s.

Racism played a big part – African-Americans needed to be able to defend themselves from violent racist attacks, and thought that martial arts would give them an edge in street fights.

There was also a wider cultural element tied in to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Before the assassination of Martin Luther King, when racial equality in the US seemed to be a real possibility, martial arts skills were seen as an expression of African-American pride, and played into black people’s hope for a better future.

After King’s assassination in 1968, when the dream of racial equality died, martial arts became a manifestation of rebellion.

Taking their cue from the heroes of martial arts films, who were often fighting for the just treatment of the Han against oppressive forces like the Manchus or the Japanese, black-run dojos became important social and organisational centres for African-American communities.

In the political sphere, armed revolutionary group the Black Panthers trained in martial arts and lauded the disciplined approach of martial arts practitioners.

The story of African-American martial arts legend Ron Van Clief, who was nicknamed “The Black Dragon” by Bruce Lee, and who starred in Hong Kong films like The Black Dragon’s Revenge (1975), shows the impact of racism on African-American martial artists.

Recalling Joseph Kuo, director of low-budget 1970s martial arts movie gems

In Martha Burr’s enlightening documentary The Black Kung Fu Experience, Van Clief talks about how he was beaten up by a vigilante mob for not sitting in the “coloured section” of a bus in the segregation era – he was hit in the face with a shovel, and then lynched, but he survived after spending four months in hospital.

Van Clief then joined the army and was sent to fight in Vietnam, where he experienced racism on his tour of duty as a helicopter gunner and an artilleryman. He left the armed forces in 1965, and swiftly took up karate.

“[Racism] had damaged my mind,” he told Burr. “Martial arts was my escape, it kept me going.”

Kung fu did not become well known in the US until the 1970s, as most Chinese masters in the country refused to teach anyone from outside their community.

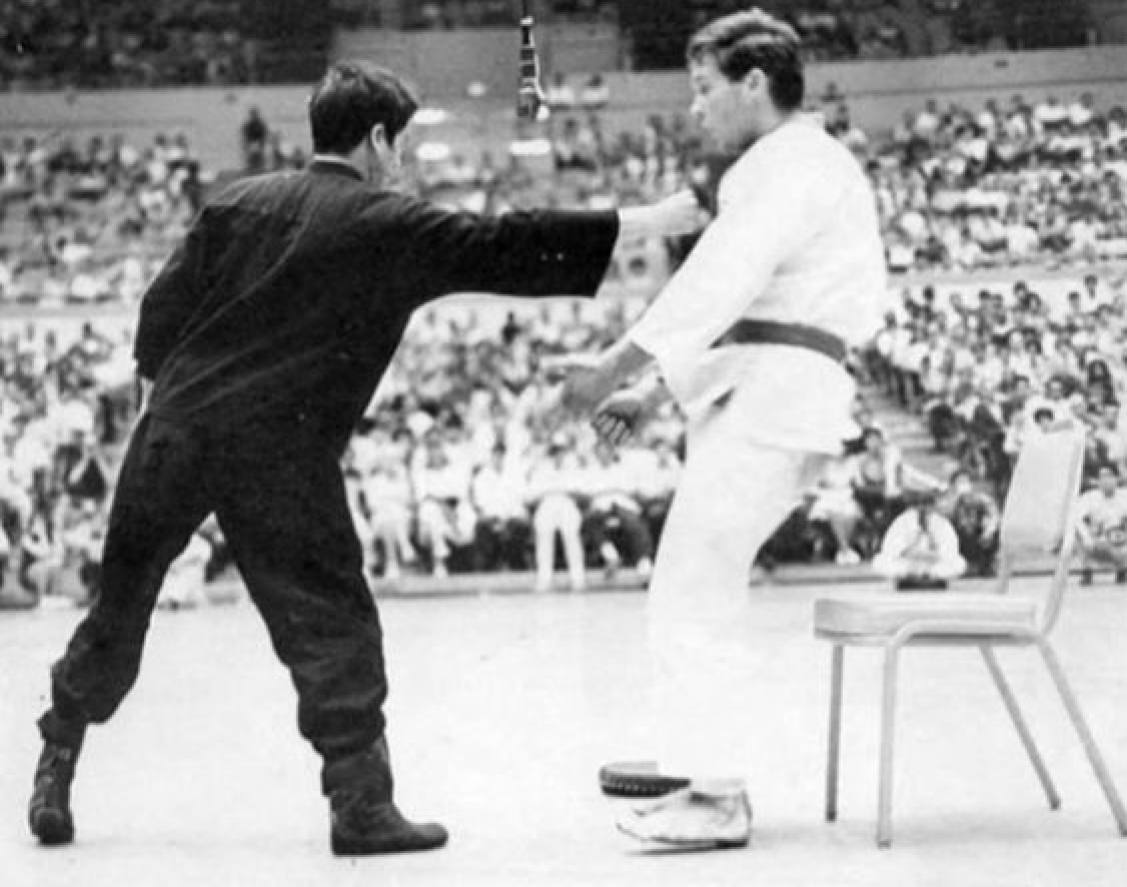

Judo was the first martial art to arrive in the US in 1912, and karate was popular with American soldiers returning from Japan after the second world war, but few had encountered kung fu. African-Americans often learned how to practise kung fu by watching Hong Kong movies in Chinatown cinemas.

“When we went [to the cinemas] as martial arts aficionados, we would be the only black faces,” American film producer Warrington Hudlin, a black belt in jiu-jitsu, told the TV show Cinema AZN.

“We saw the films to learn the techniques. In those scenarios, guys were doing techniques that they would not show you in the dojos. So we would go into the movie theatre, sit in the back row, and watch the movie over and over again. In the intermission, we would go out into the hallway, and practice the moves.”

Martial arts pioneer Dennis Brown would hop around the five cinemas in New York’s Chinatown at the weekend and watch five double features. He would remember the moves and then integrate them into his training.

Bruce Lee was a big inspiration, said Van Clief. “You saw a lot of inner city kids identifying with Bruce Lee … because he understood that whole underdog thing.”

Hudlin goes even further, saying that Lee had a good understanding of African-American culture himself. “Bruce Lee, besides his superior martial arts skills, had a real affinity for African-American culture.

The cultural admiration went both ways, noted Hudlin. “I think the emphasis on style [in kung fu films] connected with African-Americans. We share that emphasis on style, that emphasis on ‘cool’. It was not foreign to us, this notion that you have to have style and be cool. These are shared ideas.”

Movies for African-American audiences weren’t produced until 1970, when savvy distributors and low-budget film producers realised that black audiences would go to see films in which they were the heroes, rather than the villains they were forced to portray in mainstream cinema.

The widespread acceptance of Hong Kong martial arts films by the black community in the US ultimately led to their popularity among white audiences, said Hudlin. “Since American culture follows Black American culture, the way Hong Kong films were embraced and praised happened because African-Americans endorsed them first,” he said.