Advertisement

From Jackie Chan to Chang Cheh, seven legends of Hong Kong martial arts cinema behind the camera

- An ambitious star, a thinker, a businessman, a traditionalist, a visionary, an internationalist and a wild card: 7 giants of martial arts film behind the camera

- Among them, Jackie Chan used his star power to produce and direct, Chang Cheh pulled the strings at Shaw Brothers and Tsui Hark revived the genre in the 1990s

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

How did a small city like Hong Kong come to dominate global martial arts filmmaking?

No one can make such films as well as Hongkongers, for one, and its filmmakers have consistently shown hard work and imagination.

We look at the key industry players – some of whom were also performers – who made Hong Kong films such a success at home and abroad.

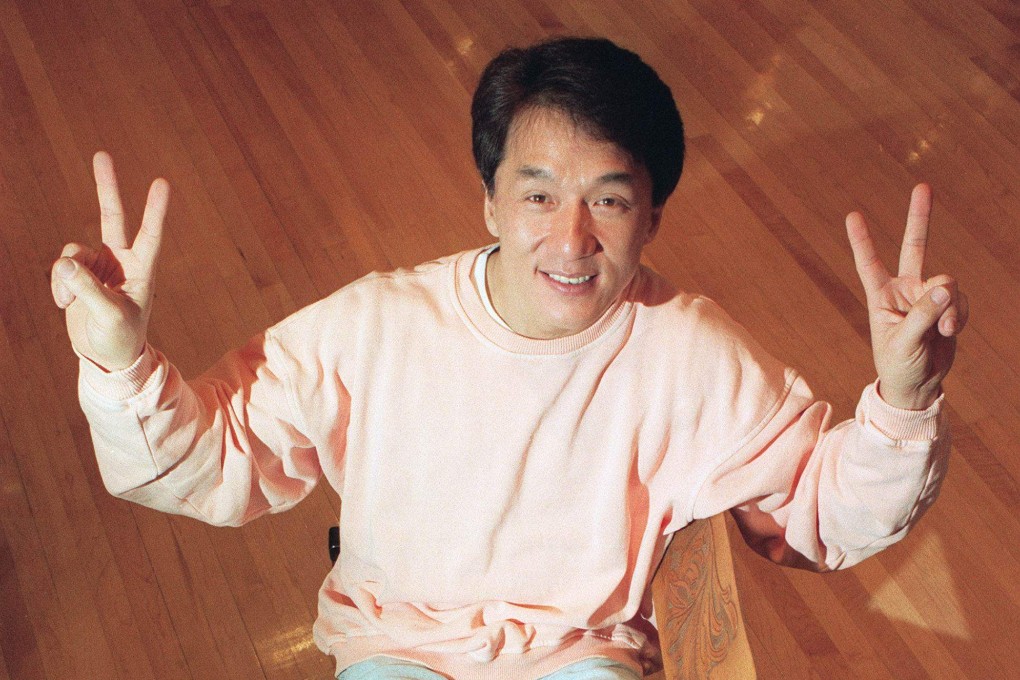

1. Jackie Chan, the ambitious star

Jackie Chan’s reputation as a hard-nosed businessman and producer often surprises his international fans.

Advertisement

Following Jimmy Wang Yu and Bruce Lee, the always ambitious Chan was one of the first martial arts performers to realise that directing his own films would bring him the creative freedom that he desired, and directing was a condition of signing his contract with Golden Harvest in 1980.

Chan used his star power to bolster his role as a producer, even though he always worked within the confines of the Golden Harvest studio. He was allowed around a year to make his films, which was unprecedented in the city’s quick-fire moviemaking industry.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x