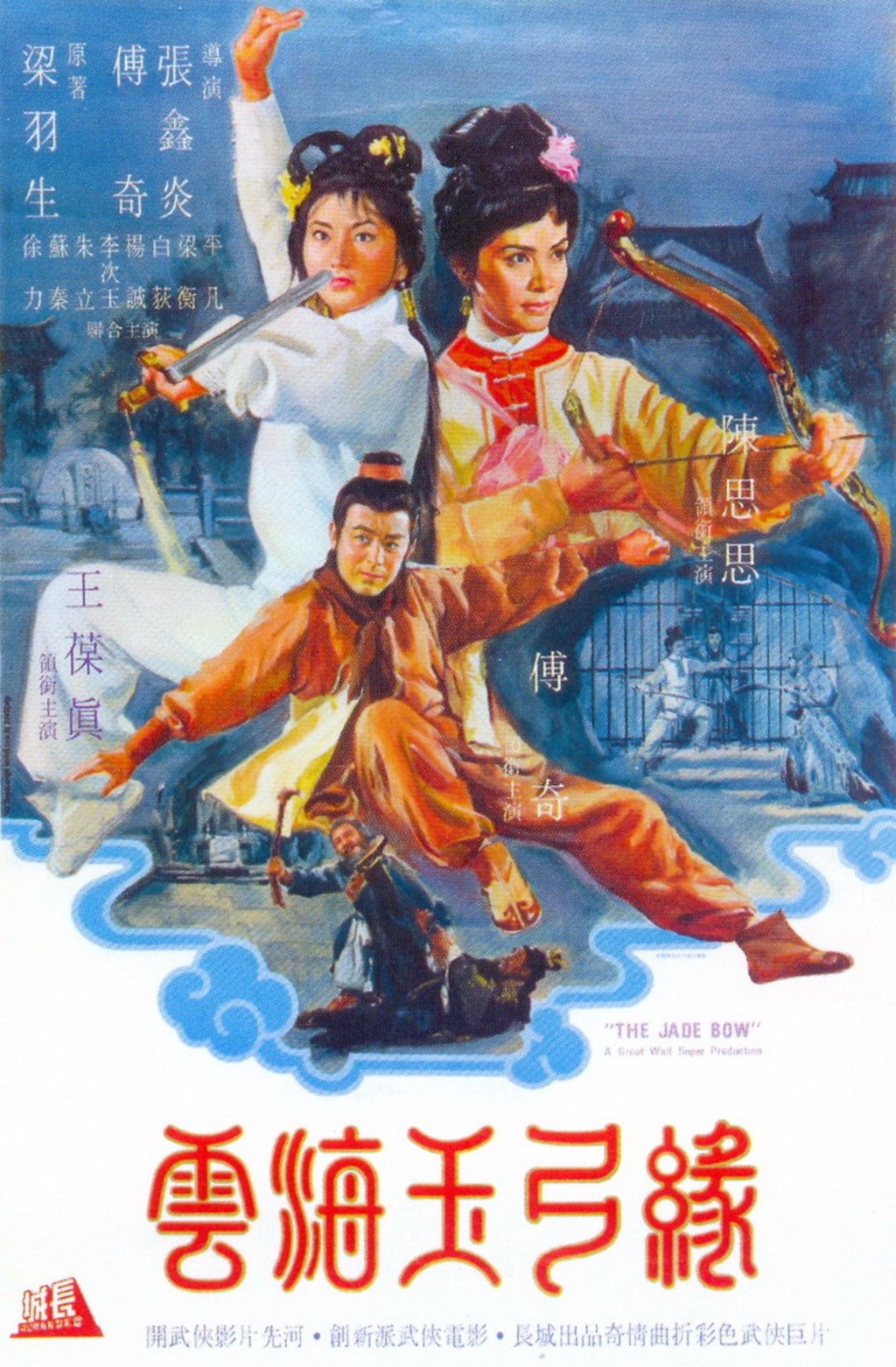

How forgotten martial arts gem The Jade Bow ushered in New School wuxia films in Mandarin Chinese

- Although difficult to find or see today, 1966’s The Jade Bow was often mentioned in the 1970s as a movie which foreshadowed the New School wuxia films

- Its sword-fighting scenes are strikingly modern and were choreographed by Lau Kar-leung and Tong Kai, who would go on to revolutionise martial arts filmmaking

But the almost forgotten 1966 movie The Jade Bow, which predated those classics by four months, was often mentioned in the 1970s as an innovative work which foreshadowed a boom in martial arts films shot in Mandarin (as opposed to the Cantonese, spoken in Hong Kong, in which many popular martial arts films produced in the city at the time were shot).

“The Jade Bow is an intricate network of relationships,” wrote a local critic in 1980. “With its synthesis of melodrama and vigorous fight sequences, The Jade Bow helped to lead the rise of the new-style wuxia (sword-and-sorcery films) of the 1960s.”

The film’s lack of visibility is probably because The Jade Bow was produced outside the Shaw Brothers/Golden Harvest Studio system – it was made by the left-wing studio Great Wall – and is therefore difficult to see today.

It was released on DVD by Mei-Ah in the early 2000s but is not currently available and, if a usable print still exists, it has not been screened outside festivals in Hong Kong, where it last showed in 1997.