How Wordle alternative Globle, a geography quiz, made its world map when national borders are in different places for different people

- Like Google Maps before him, Globle creator Abe Train quickly realised he needed a rational framework for adjudicating geopolitical disputes

- How only noticed after launch that the country data he used displayed the disputed peninsula of Crimea in Ukraine as belonging to its current occupier, Russia

The geography quiz game Globle was a product of quarantine boredom, its popularity a happy side effect.

While stuck working from home during the Covid-19 pandemic, Abe Train, 26, of Toronto, Canada, decided to study web development, quit his corporate job and try something new. Inspired after the simple web-based word game Wordle gained widespread popularity in January, Train created an imitator just to practise his skills.

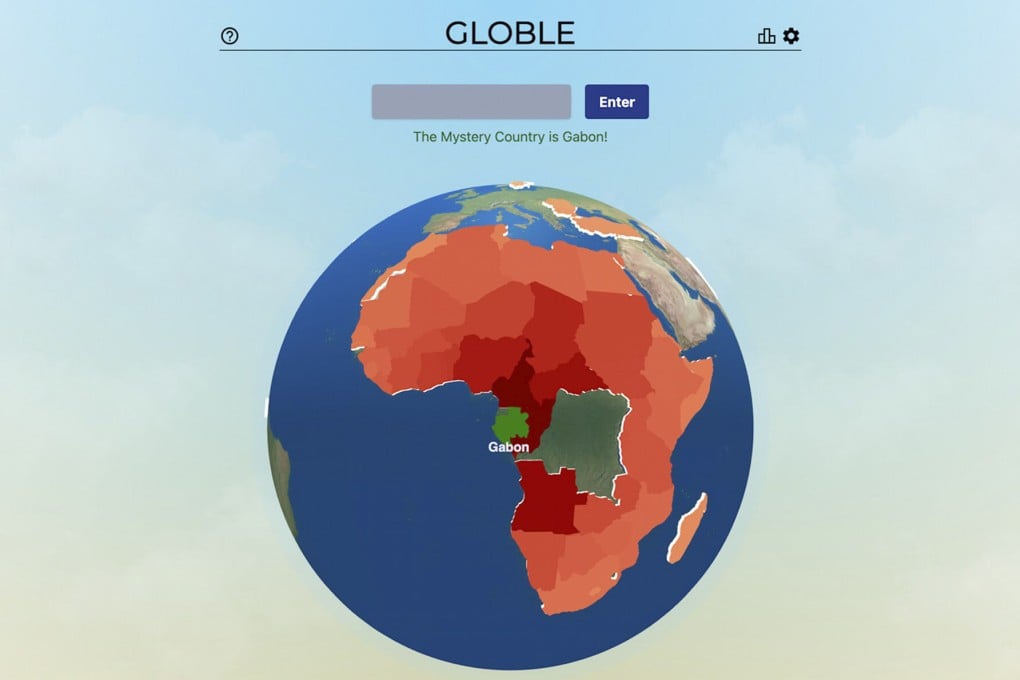

Globle’s rules are simple: “Every day, there is a new Mystery Country,” Train says. “Your goal is to figure out the mystery country using the fewest number of guesses. Each incorrect guess will appear on the globe with a colour indicating how close it is to the Mystery Country.”

If the mystery country is Germany and you guess China, China appears in pale beige on the globe, indicating the correct answer is far away. A guess of France – getting closer! – appears in dark red. Winning requires a fairly decent knowledge of the names of the world’s nearly 200 countries, a sense of where they are and, just as important, who their neighbours are.

As in life, learning from wrong answers is a key part of finding the right ones, and to Train’s surprise, a lot of people decided his home-cooked practice project was an easy way to brush up on their geography.

After picking up traction on Reddit and then Twitter, Globle now averages about 1.3 million to 1.4 million players a day, according to Train, who has declined to place ads on the game.