Brigitte Lin’s first gender-neutral role, Sally Yeh’s butch Beijing Opera performer make Tsui Hark’s 1986 period comedy Peking Opera Blues highly enjoyable

- Hong Kong director Tsui Hark’s 1986 film Peking Opera Blues, set in the Chinese Republic era, put women in the spotlight and challenged gender stereotypes

- With Brigitte Lin cross-dressing as a warlord’s daughter, Sally Yeh as a ‘butch’ Beijing Opera performer and Tony Ching action sequences it’s an enjoyable caper

Thirty six years after it was released, Tsui Hark’s lively Peking Opera Blues (1986) remains one of his most enjoyable movies.

A mix of action, comedy and light drama, the film follows the exploits of three women in 1913, the second year of the Chinese Republic. Although it’s set amid the chaotic politics of the time, the political shenanigans simply serve as the backdrop for an entertaining caper movie which is heavy on stylistics and light on message.

The story, neatly crafted by acclaimed playwright Raymond To Kwok-wai, is a fictional tale set amid the real-life events of 1913.

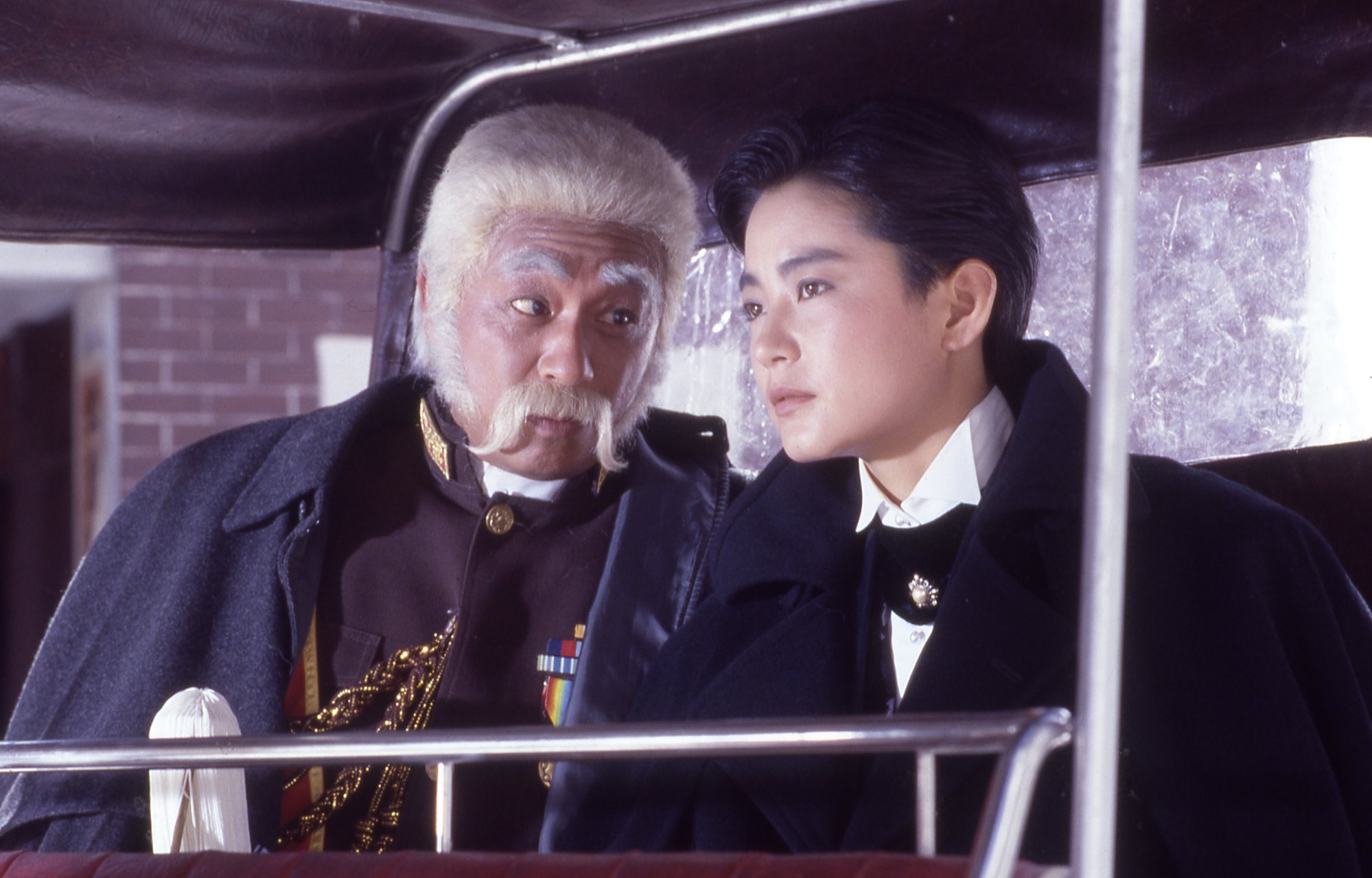

Lin, who dresses in masculine Edwardian clothes, is a Republican spy who’s trying to intercept the document that will enable her father to fund Yuan’s plot.

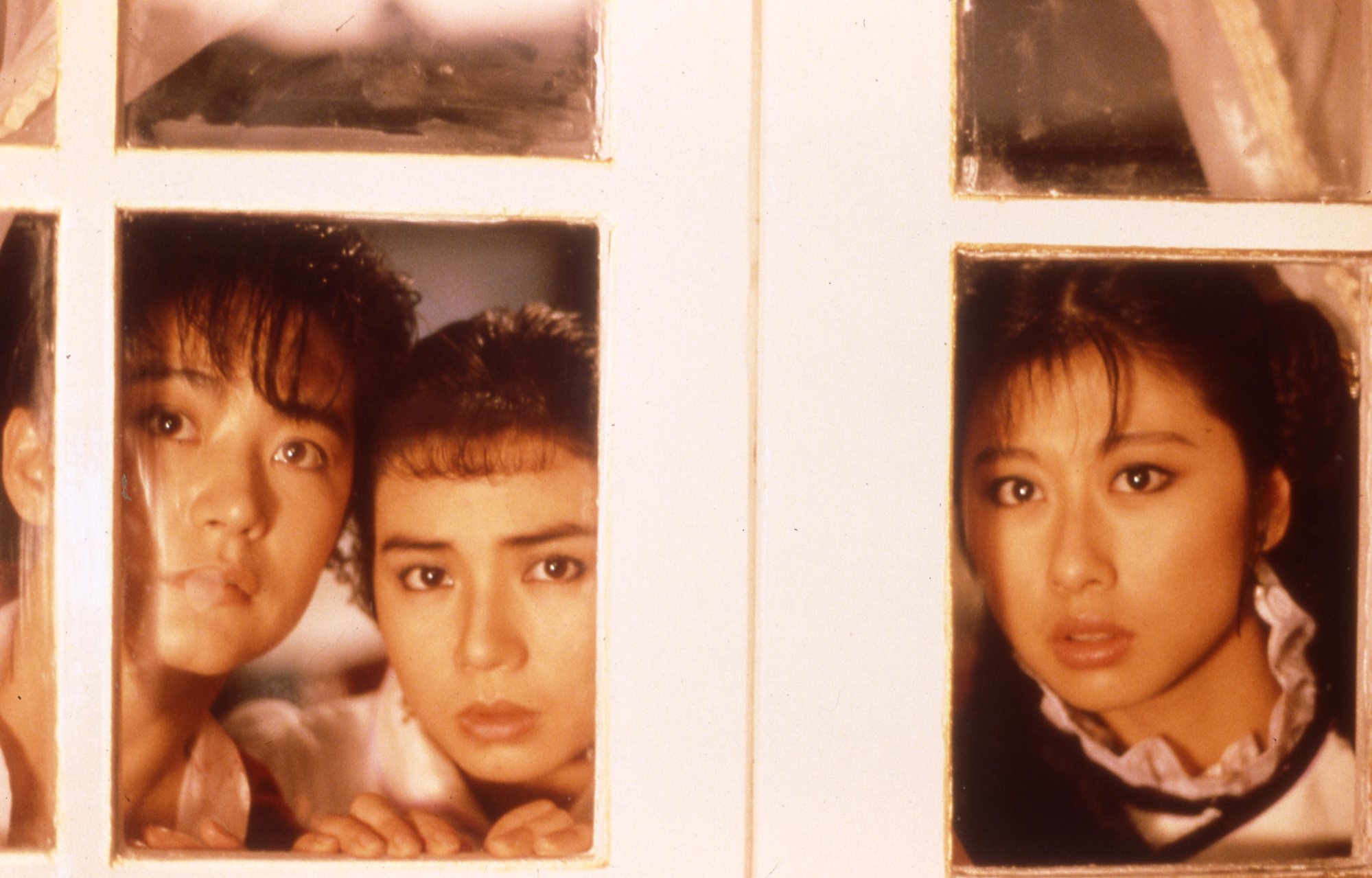

Together with Sally Yeh Chian-wen’s singer character, and a gold-digging escort played by Cherie Chung Cho-hung, Lin schemes to outwit her father and save the Republic. Meanwhile, the daily ups and downs of the opera company become mixed up in Lin’s plans.

Although it came directly after Tsui’s little-seen slapstick comedy Working Class, the director intended the film to be part of a trilogy with 1984’s Shanghai Blues, his lavish wartime comedy.

Tsui said in a television interview: “ We filmed Peking Opera Blues after Shanghai Blues, and I intended there to be a third film to make a trilogy. The idea was to connect the people from the different times in the films together by putting a third film in the middle. But the other film was never shot.”

The two films remain connected by Yeh, who also plays a singer in Shanghai Blues, and the use of the word “blues” in the English titles. The word relates to the musical term, and is meant to express the downbeat mien of the characters.

The Chinese title is more descriptive, translating as Knife, Horse, Actresses – a phrase used in Beijing Opera to denote men who play women.

Peking Opera Blues sees Lin wearing men’s clothing, including an Edwardian-style military outfit. The character explains, somewhat unconvincingly, that this enables her to blend in and move unconstrained in a male-dominated society.

Tsui’s interest in using an opera setting was piqued by a scene featuring characters singing on the rooftops in Shanghai Blues. “There were no female performers in Peking Opera at that time,” Tsui said. “The traditional moral perception was that women should not be too outgoing, and they should not perform on the stage, as that was thought to be indecent.”

“If you put a woman in the setting of Peking Opera, wonderful things happen naturally. That’s why we focused on it.”

Critics tend to focus on Lin’s performance today, but Yeh and Chung were her equals when the film was released, and the screen time is equally split between the three. Yeh is impressive, handling her humorous Beijing Opera performances with aplomb, while Chung overacts but is charming nonetheless.

Yeh trained in Beijing Opera for seven months for the film, learning the form’s gestures and weapons techniques.

“My character Bai Niu was a lot like me – she’s a big and blowsy girl who says what she thinks,” Yeh said in an interview. “She was a bit butch, and she was opinionated and full of herself. Tsui showed me a lot of films for reference – he really knew how to train an actor.”

Tsui decided to feature women in the main roles as he was bored with seeing the same male faces in local comedies which pushed women into the background. “Everyone felt that a change was needed in Hong Kong comedies of the time,” he said.

It can be said, though, that the film was part of a longer tradition. In his book about the film, scholar Tan See Kam notes that Peking Opera Blues is a late entry in the “three women” literary and film genre that was popular in China in the 1920s and 1930s. The genre was characterised by intertwined stories of three female protagonists, who usually had romantic problems.

Tsui updated the characterisation to reflect women’s rising social status in Hong Kong in the 1980s, Tan wrote.

Tsui has sometimes said that Peking Opera Blues is a comment on democracy in China, but that’s not borne out by the content – the characters express no political views, and political ideology is not discussed at all.

The film’s exuberance is certainly infectious. “I want to give the audience hope that they can overcome difficulties and have a bright future – a better tomorrow!” Tsui said.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.