Why Brad Pitt was banned from China after 1997 movie Seven Years in Tibet

- China was unhappy with Seven Years in Tibet, which was essentially a 136-minute plea for Tibetan freedom with Chinese characters that do not come off well

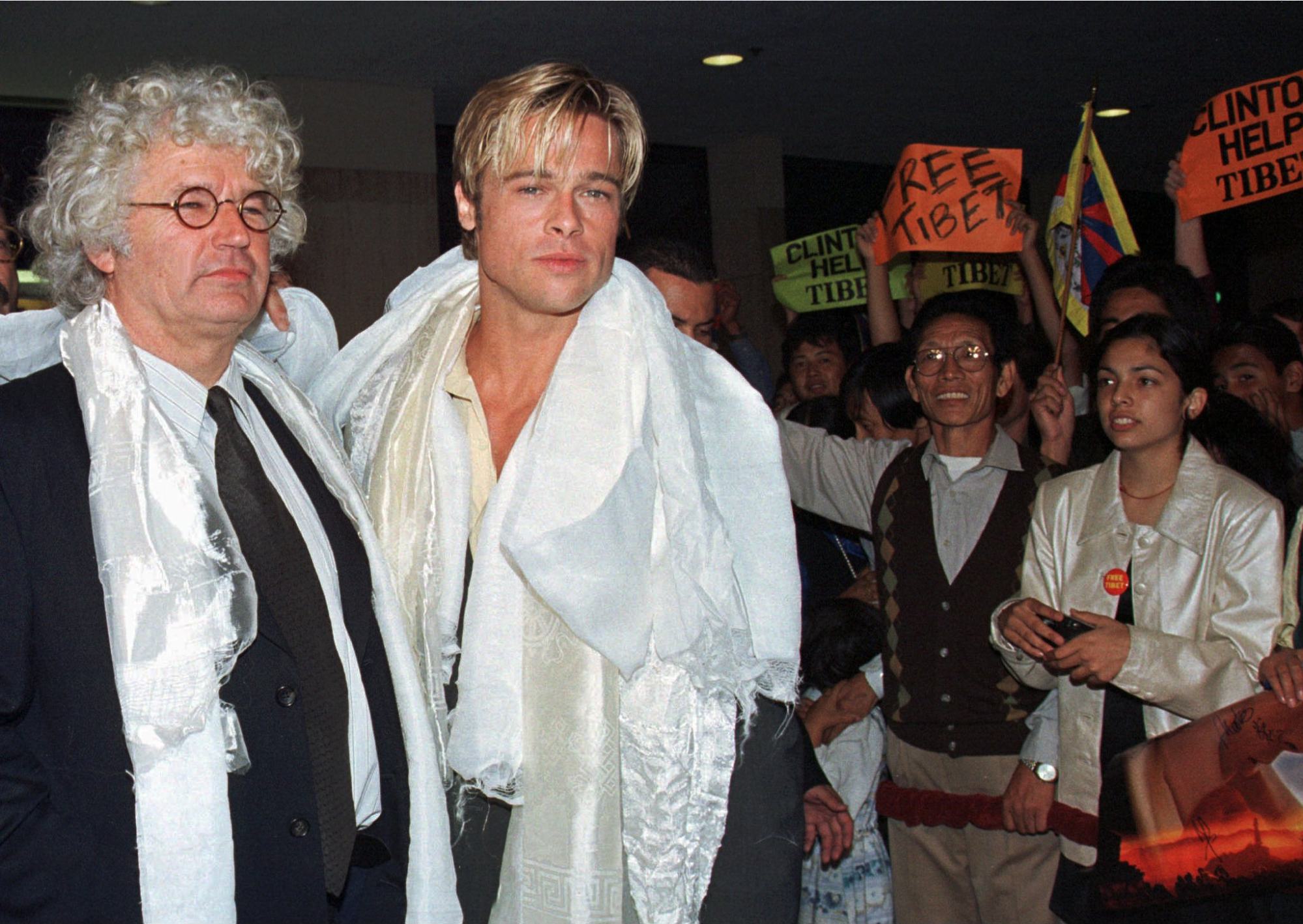

- Stars Brad Pitt, David Thewlis and director Jean-Jacques Annaud were banned from the country, and Sony’s multibillion-dollar business empire was put at risk

In 1997, Brad Pitt had the world at his feet. Combining box office appeal with critical approbation, he’d already worked with some of Hollywood’s best directors (David Fincher, Terry Gilliam, Tony Scott) and was looking to spread his wings even further.

Seven Years in Tibet – based on the 1952 memoir by Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer (1912-2006) and directed by the acclaimed French filmmaker Jean-Jacques Annaud (The Name of the Rose) – seemed like the perfect choice.

While climbing the Himalayas in the run-up to World War II, Harrer (played by Pitt) is captured and interred in an Indian prisoner-of-war camp. He and his friend Peter Aufschnaiter (played by David Thewlis) escape in 1944, then cross the border into Tibet.

Here, they are welcomed into the holy city of Lhasa and, eventually, the inner circle of the teenaged 14th – and present-day – Dalai Lama (played by Jamyang Jamtsho Wangchuk). But after the Chinese occupation in 1950, Harrer is forced to bid goodbye to the Dalai Lama, who had become his protégé, and return home to Austria.

It’s a hell of a story, albeit with a few obvious stumbling blocks. Harrer was an officer in the Nazi paramilitary, a fact that the film admits, but downplays.

He was also furiously unlikeable: he left his pregnant wife to go climbing, endangered Aufschnaiter at every turn and generally acted like a spoiled brat.

Shot in China, why did Ultraviolet starring Milla Jovovich go so very wrong?

Then there’s the accent, which Pitt attempts with admirable, if ill-advised, gusto. You’ll never hear the word “Himalayas” quite the same again.

Although there’s a pleasing symmetry to proceedings, with Harrer’s arrogant pursuit of earthly goals contrasted with the Dalai Lama’s simple spirituality, it’s the off-screen drama that would come to define the film, and Pitt’s involvement in it.

In the mid-1990s the Dalai Lama was something of a celebrity. He had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, guest-edited French Vogue in 1992, and been championed by the likes of Richard Gere, Sharon Stone and Steven Seagal.

China, however, was not happy, seeing his new-found fame as a challenge to its sovereignty.

According to the book Red Carpet: Hollywood, China and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy by Erich Schwartzel, when the film’s production team was based in Ladakh, on the Tibetan border, the locals, under pressure from China, threatened to cut off the electricity and prevented them from opening bank accounts.

This prompted a move to the Andes in South America, where the team built a replica Lhasa and shipped in yaks from the US state of Montana.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Seven Years in Tibet’s distributor was Sony Pictures, whose parent company made most of its money through electronics produced cheaply in China. When Chinese officials saw the movie, Schwartzel wrote, they were so offended that it put the whole of Sony’s billion-dollar business at risk.

Normally this could all be fixed by a judicious edit, but the film is essentially a 136-minute plea for Tibetan freedom, and the Chinese characters do not come off well.

When faced with a mandala made of sand, “a symbol of enlightenment and peace”, Chinese general Chang Jing Wu (Ric Young) stomps right over it. He then disrespects the Dalai Lama and leaves, snarling, “Religion is poison!”

Harrer’s voice-over also explicitly aligns the invaders with the Nazis, saying they are “no different than these intolerant Chinese”.

China, meanwhile, turned its ire on the people involved in the film, banning Annaud, Pitt and Thewlis from entering the country – an exile that lasted far longer than seven years. Annaud was welcomed back in 2012, while Pitt did not return until 2014.

In 2013, Pitt joined Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, to say: “It is the truth. Yep, I am coming.” A few hours later, the post disappeared.