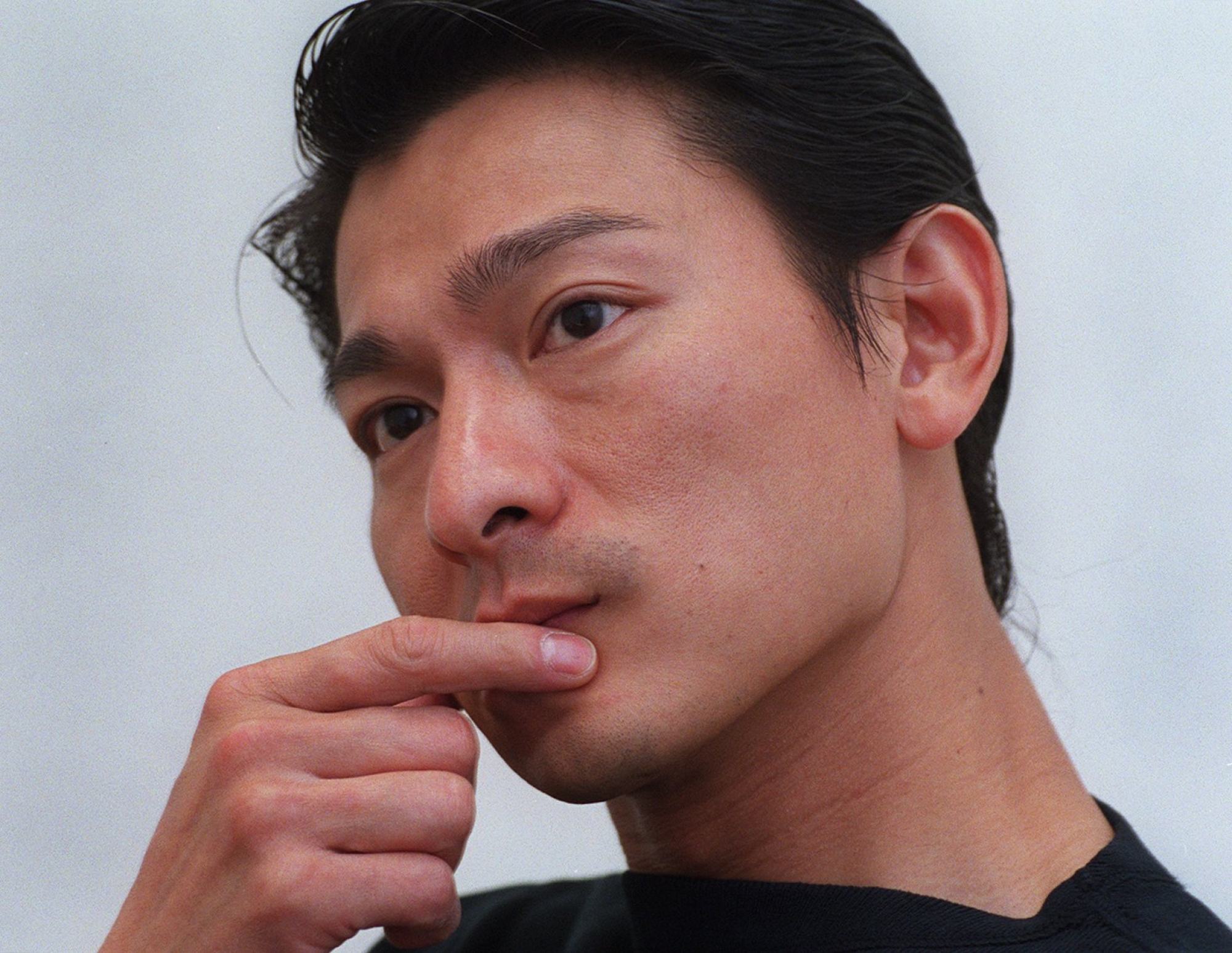

Andy Lau, Hong Kong actor and singer, on his ‘good enough’ career, being a ‘very lucky guy’, and why Hollywood didn’t tempt him

- One of the ‘four heavenly kings of Cantopop’, Andy Lau has appeared in everything from popular commercial films to art-house movies, and been a film producer

- In interviews with the Post he has talked about how he rates himself, why he enjoys being busy, not being drawn to Hollywood and accepting his own limitations

Andy Lau Tak-wah has long been Hong Kong’s most popular entertainer.

Lau has also worked as a film producer, putting his notable business acumen – “I don’t have a problem with money as I spend less than I earn,” he once told the Post – to work nurturing fresh talent.

Below, we recall what Lau has said about his career and the Hong Kong film industry in interviews with the Post.

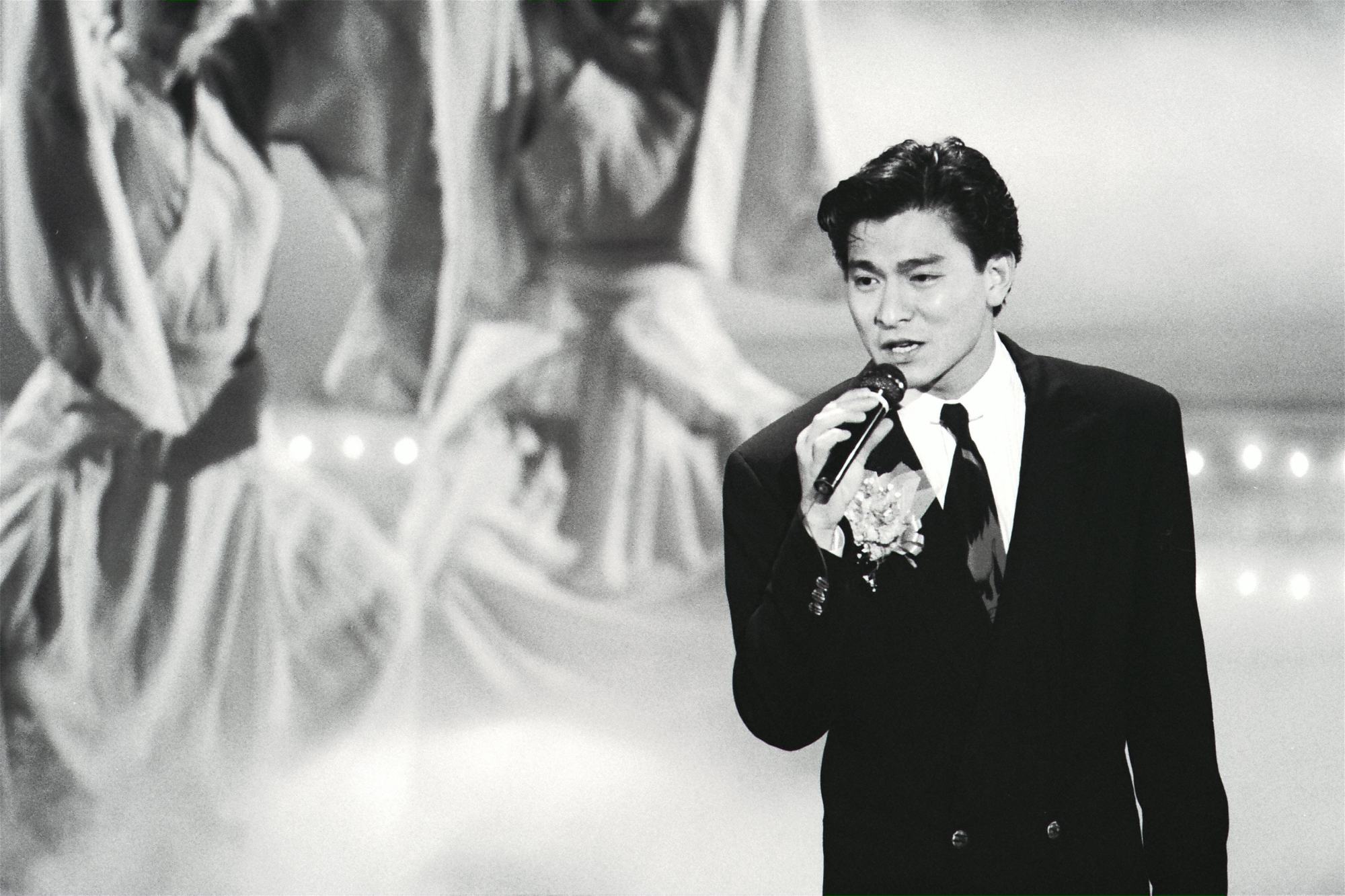

On always being rushed off his feet, in an interview in 1992:

“I don’t mind being so busy. Because I’m in both careers, acting and singing, it takes a lot of my time. I do prefer singing over acting, but really I love to do both.”

On his own personal scoring system, in an interview with Winnie Chung in 1996:

“I think time has a great effect on the quality of your work. You can do 100 things and get 80 marks for your effort. If you want to get 100 marks, then maybe you won’t even be able to do 10 projects in a year.

Reservoir Dogs with more charismatic actors: Ringo Lam’s City on Fire

“In the past, I think I may have earned 70-something marks for my efforts but recently that has gone up to 80-something. Before, the most important things to me were fame and fortune, and security.”

On how he feels about his success:

“It is a case of ‘one catty, eight taels’. I have put in one catty’s work but I have got back more than eight taels. I don’t think it has been bad. In fact, I think by choosing this path I may have learned more than I would have doing anything else.

“Other than knowing how to act, I have also learnt to be a better human being. I always wanted people to say I was a good actor or a good singer. When they did, I would always feel secretly proud of myself. That feeling is gone now.”

On how he feels about his films, to Winnie Chung in 2001:

“I’ve done more than 100 movies, but I have to ask myself how many of those did I really like and how many did I do for the money? I don’t need to do it for the money any more so now I want to do the kinds of films that make me happy and that can help the industry as well.”

If I leaned against a wall, in a singlet and with a cigarette in my mouth, I wouldn’t look artistic; I would look like a Teddy Boy.

On coming to terms with his own limitations:

“After you watch a lot of movies, I think you begin to realise you cannot star in every movie.

“I’m seeing a lot of things more clearly now – maybe it is a sign of maturity.”

On his good fortune:

“I’m a very lucky guy. Not a lot of people can have their lives so much in tandem with the changes around us. I have the ability and I work hard, but the same goes for a lot of other people. It’s a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

On how his career started, in an interview in 2008:

“I entered the TVB artist training class when I was about 17 and joined the industry after training at about 19. That was in 1980. I finished Form Six but I did not want to continue my studies, as I was not good at academics.

“I decided to go into show business because I liked drama and wrote a screenplay when I was in Form Two or Form Three. Initially, I aimed to be a director, but my teacher classified me as an actor, so he chose the career for me.

“My first performance was to act as one of the many students in a classroom in a TV show called Four Seasons Love. I was paid HK$60 or so. After completing the training, I received about HK$1,800 a month.

“After giving HK$1,500 to my family, I acted as a private tutor to primary school students and sang at a piano bar to earn some extra money.”

On his early days in the entertainment industry:

“I did not think it was so hard. I came from a [poor] family. My father was a firefighter, I have three elder sisters, one younger brother and a younger sister. I was more than happy to get the TVB contract to support my family.

“Baleno has sponsored my clothing since 1982, so I have saved on expenses. I earned my first fortune from the movie Boat People in 1982 and I decided to buy a piece of property.

“A year later, I bought a flat in Broadcast Drive for HK$470,000 for my family. Six years later, I sold it for HK$1.2 million. That was a good start.”

On how superstardom had not changed him:

“Acting and singing are ways to communicate with those who grew up with me. I could not abandon my supporters just because I have earned enough money to quit.

“Money is not my priority. In fact, I think I am the lowest-paid artist in the city because I am willing to give up part of my payment to pay for production costs.

“You can say I am investing in myself. I want to produce the best films and the best concerts for my audience, to win their respect for me. I want my supporters to be proud of my performance. I may receive less, but getting people’s respect is a high return.”

On not going to Hollywood:

On his career path, in an interview with Edmund Lee in 2013:

“There are no predestined results or preset course of events. It’s like in those early days, people were saying, ‘Andy Lau is doing so great. He left TVB and has now become a big star.’

“But then you realise [Tony] Leung Chiu-wai stayed at TVB [after I left] – and what now? We’ve both arrived at the level we wanted to reach.

“As long as you have learned to enjoy your life, and you’re happy with both the effort you made and the reward you receive over that period, that’s good enough.”

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.