Explainer | What happened in Hong Kong cinema during the 1970s beyond Bruce Lee and the New Wave movement: Michael Hui, Jackie Chan, the rise of kung fu and sex movies, and more

- At the start of the 1970s, there was Bruce Lee. At the end, there was the Hong Kong New Wave. We take a look at what went on between the two in Hong Kong cinema

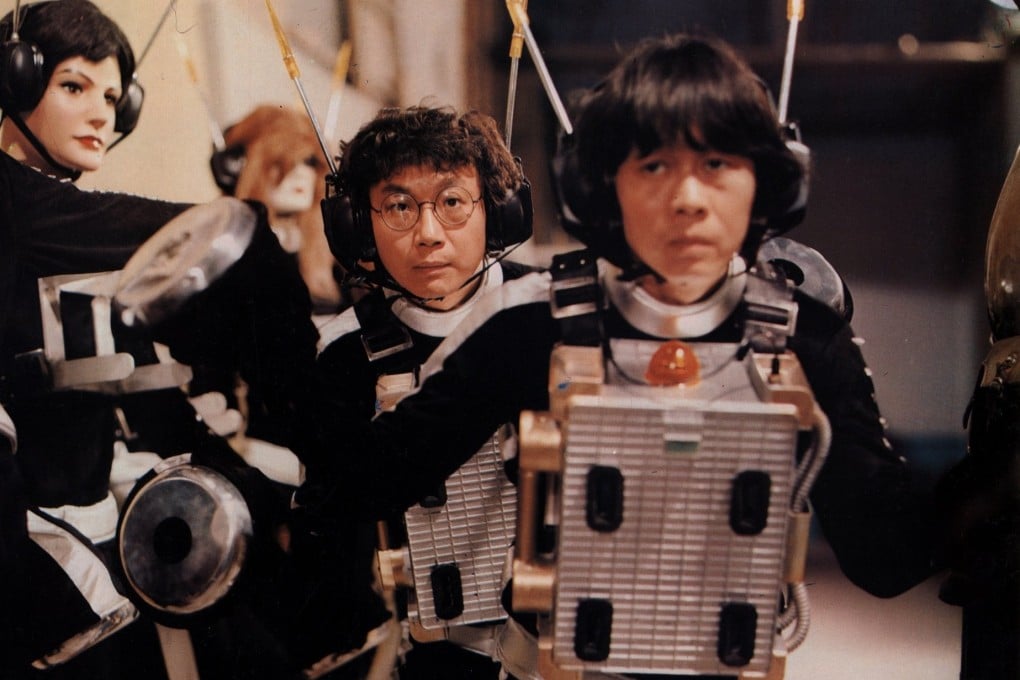

- Michael Hui’s comedy connected audiences with his films, kung fu got real – as did sex – the police film genre was born and Jackie Chan achieved stardom

But a lot happened in between. Here we take a look at the “other” 1970s.

Fun at the box office

According to a 1978 chart of all-time local box-office hits, Hui’s The Private Eyes (1976), The Contract (1978) and Games Gamblers Play (1974) held the top three spots.

Lee did not make an appearance until Way of The Dragon (1972) showed up in seventh place, behind foreign blockbusters like Jaws and The Towering Inferno, and Chor Yuen’s popular satire House of 72 Tenants (1973).

Hui’s films were hilarious, but they also connected with audiences because they were the first movies to define a specifically Hong Kong – rather than Chinese – culture.

Coming at a time when the colonial government was riven by corruption scandals, Hui’s films depicted average citizens – albeit hilariously exaggerated ones – standing up for themselves against the excesses of authority.