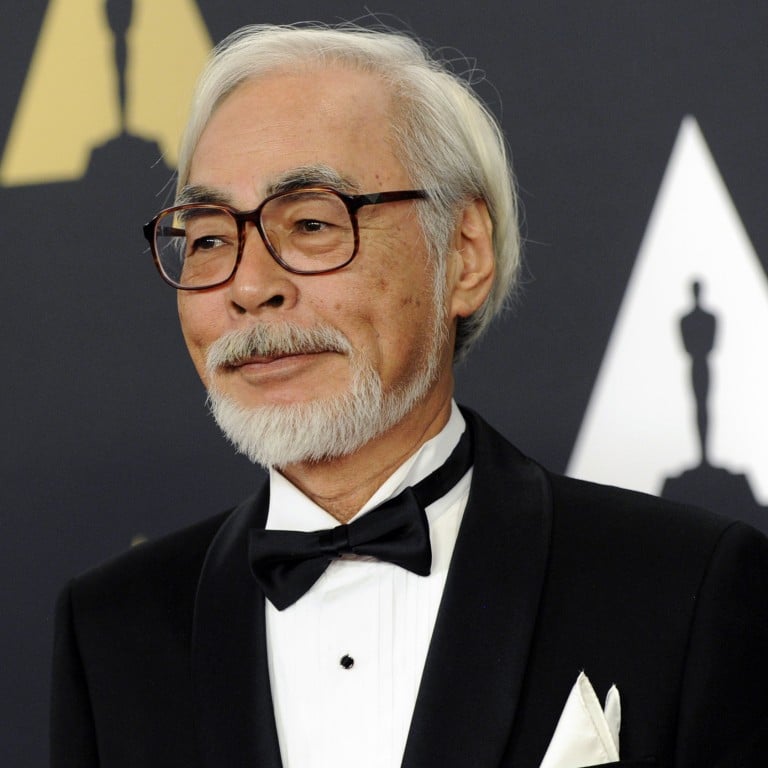

Profile | Hayao Miyazaki: the career of anime legend, 83, behind Studio Ghibli, who won his second Oscar for his ‘final’ film The Boy and the Heron

- Miyazaki, who won an Academy Award in 2003 for best animated feature for Spirited Away in 2003, has won the award again, for The Boy and the Heron

- We look back at the life and work of the 83-year-old animator and Studio Ghibli co-founder, who has described his work as an ‘agonising struggle’

An Oscar win two decades ago introduced the world to Japanese anime great Hayao Miyazaki, and now the Studio Ghibli co-founder, aged 83, has done it again.

Enthralling viewers of all ages with his extraordinary imagination, the animator has built a cult following through films depicting nature and machinery in fantastic detail.

The beloved characters dreamt up by Miyazaki include cuddly yet mysterious spirit creature Totoro – the mascot of his celebrated production house.

But despite becoming one of Japan’s top cultural exports and helping take anime mainstream, he describes his work as an agonising struggle and has retired several times, albeit unsuccessfully.

Miyazaki’s 1997 breakout feature Princess Mononoke, the tale of a girl raised by wolves in a forest threatened by humans, set him apart from rivals such as Disney, who tend to focus on the battle between good and evil.

The Boy and the Heron: Hayao Miyazaki goes out on a high

The director said at the time that he “didn’t want to say what’s right and what’s wrong” in the film.

On another occasion, the aviation-loving pacifist said that making a film was not a logical process.

“I start to descend into the well of my unconscious. Then a lid at the bottom of the brain opens. This allows new directions to emerge, which were unimaginable when I was thinking with just the brain’s surface,” he told reporters in France. “But it’s better not to open it. It’ll almost always pose problems to your family and social life.”

Born in 1941 to a well-heeled Tokyo family, Miyazaki grew up an avid fan of manga comics. He was at high school when Japan’s first colour anime film came out, and said he was so moved by it he cried all night.

After studying politics and economics at university, he launched his career as a staff animator at Toei, a major studio.

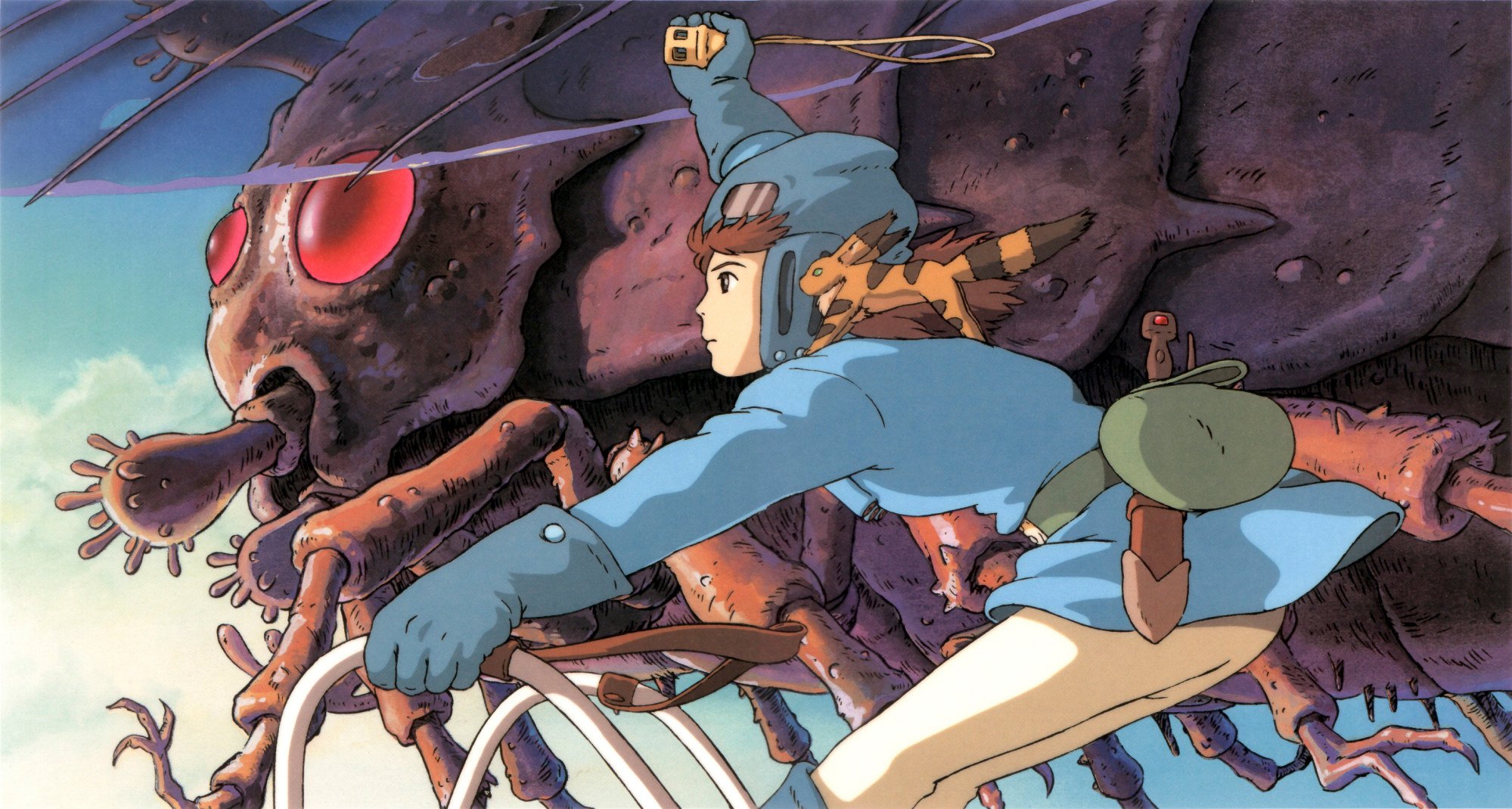

His debut feature The Castle of Cagliostro was released in 1979, and told the story of the grandson of fictional French thief Arsene Lupin. Miyazaki’s fame grew with Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind in 1984.

The following year, he and fellow animator Isao Takahata founded Studio Ghibli, which grew into Japan’s premier anime studio, revered by fans worldwide.

Ghibli is an Italian word derived from the Arabic word for a hot Saharan wind. It is also the name of a type of military plane and was chosen to symbolise their desire to breathe new life into the animation world.

Like many Miyazaki films, Spirited Away features a female protagonist, and blends themes of nostalgia, greed and interaction with the natural world.

“Fantasy is necessary for children to escape from the tough reality they face,” he told the Asahi Shimbun that year.

Miyazaki is a prominent liberal figure in Japan, and made headlines in 2015 when he criticised then-prime minister Shinzo Abe for saying future generations need not apologise for the country’s war record.

He urged Japan’s leaders “to say clearly that aggressive war was completely wrong, having brought enormous damage to the Chinese people”.

The heavy smoker announced in 2013 he would no longer make feature-length films as he could not maintain the hectic intensity of his perfectionist approach to work, citing “various” health problems.

However, in an about-turn four years later, Miyazaki’s production company said he was coming out of retirement to make “his final film, considering his age”.

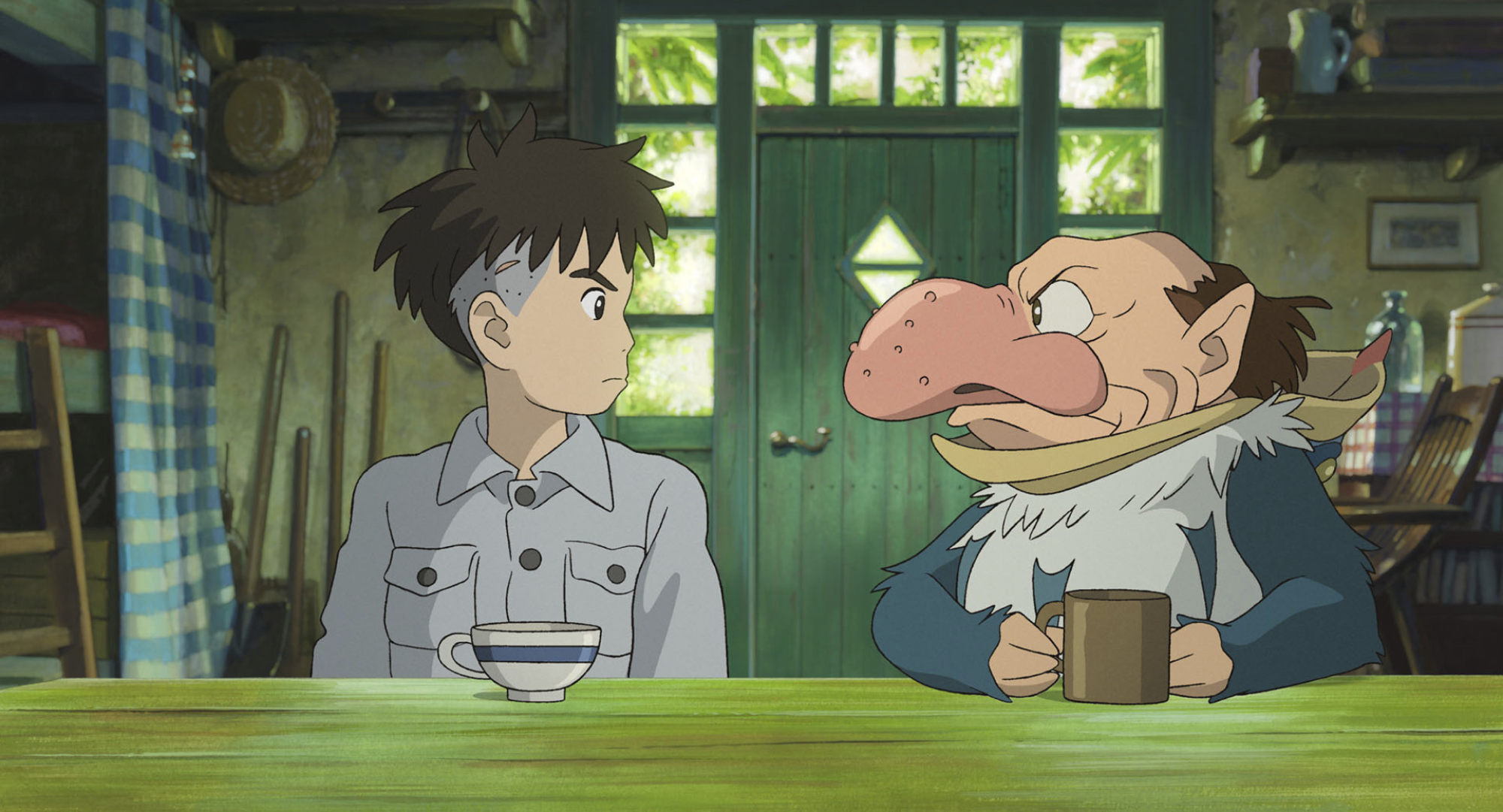

That movie – The Boy and the Heron, originally titled How Do You Live? in Japanese – was released in 2023.

It tells the story of a boy who moves to a countryside during World War II after the death of his mother in the firebombing of Tokyo, and struggles to accept his new life with his father and pregnant stepmother, who goes missing.

Everything changes when he meets a heron and embarks on a journey to an alternate universe where the living and the dead appear to coexist.

“The truth about life isn’t shiny, or righteous. It contains everything, including the grotesque,” Miyazaki said in a recent NHK documentary, in which he was visibly affected by the 2018 death of Ghibli co-founder Takahata.

“It’s time to create a work by pulling up things hidden deep within myself.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)