#MeToo victims’ campaign highlights need to educate parents and protect children from abuse

The campaign encourages sexual abuse victims to share their experiences and has given millions the courage to open up. We talk to social workers and other experts about the need for communication and to teach parents how to empower their children to reduce the likelihood of it happening to them

Connie Lam was six years old when her uncle sexually assaulted her during a sleepover with her favourite cousin. He crept into his son’s bedroom and began touching Lam (whose real name has been withheld for reasons of confidentiality). He told her it was harmless fun and their little secret. After months of repeated abuse, Lam confided to her mother. She never saw her uncle or his family again.

It was the recent outpouring of two simple words – #MeToo – on her Facebook feed that made Lam, now 42, feel less alone. Some of her friends and relatives were among the more than 12 million people around the world sharing their experiences of sexual abuse and harassment on social media. The campaign sprang up in the wake of the sexual assault allegations against film mogul Harvey Weinstein.

Police look into allegations two sisters were sexually abused at Hong Kong secondary school

“My experience, as a survivor, is unique. In that sense, I’m alone. But as a mum, I no longer feel alone. This campaign has opened up much-needed dialogue between parents on how to educate children on the risks of sexual abuse without scaring them,” says Lam, a certified accountant and mother of three.

Lam’s concerns as a parent are legitimate. In 2016, the World Health Organisation reported that one in five women and one in 13 men have been sexually abused as a child. Hong Kong’s Social Welfare Department reported 160 new cases of child sexual abuse between January and June this year. Child sex abuse experts agree that these figures are the tip of the iceberg.

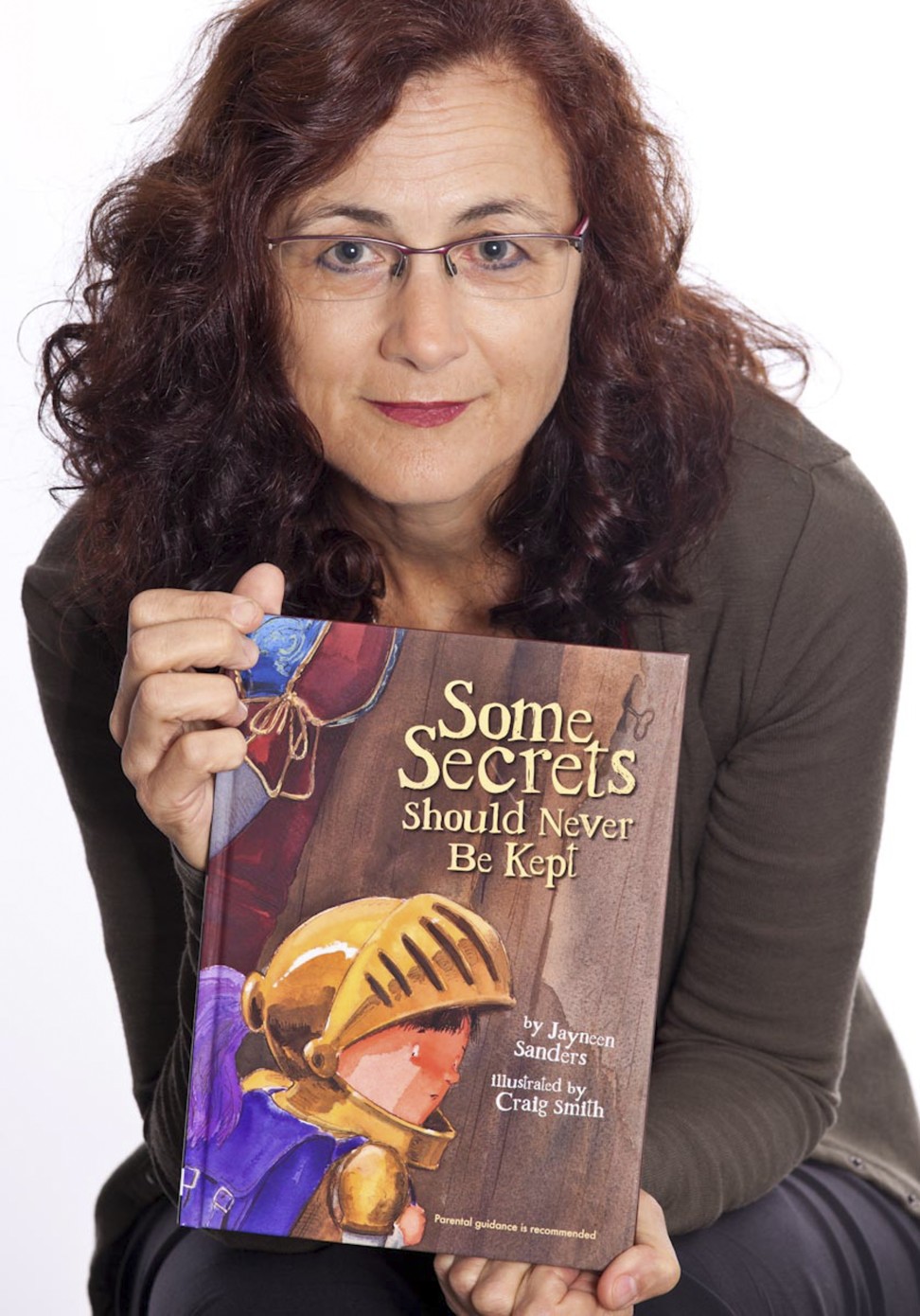

At Live Brave Workshops, life coach Rebecca Hopkins teaches parents of children under the age of 10 how to empower youngsters with tools and techniques to reduce the likelihood of sexual abuse. Her body safety workshops are based on the work of Jayneen Sanders, an Australian-based author and advocate for sexual abuse prevention education.

Body safety starts with using the correct anatomical names for body parts, including the mouth, Hopkins says. This will help children to be confident with their bodies and prevent confusion when it comes to reporting abuse to a trusted adult.

From the age of three, children can be asked to identify five adults they trust (not that you trust), who they can go to if they feel unsafe. “Have a conversation with these adults and let them know their role is to always believe your child, listen to them, and ensure they deal with the situation appropriately,” Hopkins says.

Talk to your child about their emotions and the concept of feeling safe and unsafe. This is especially important, research shows an alarming 85 per cent of sexually abused children know their abuser. Additionally, peer sexual abuse, and abuse between older and younger children are on the rise. Children should also be empowered to choose who can and can’t touch their bodies, as this will help to build their confidence.

Carrie Lam’s pledge to protect child rights is welcome, but will the commission get teeth?

“I have a rule with my kids that doctors may have to touch their private parts, but only if they ask first, and if the child has an adult they trust with them,” Hopkins says.

She recommends parents read Sanders’ books No Means No to toddlers and This is My Body, What I Say Goes! to children between the ages of five and 10. There are other books suitable for other age groups. The books promote natural conversation and awareness around body safety.

Early next year, Red Door, a psychology and counselling centre in Central, will run a workshop tentatively titled “Go-Girl” for girls aged 11 to 13. Contents include keeping girls safe online and in life, helping them understand if they are in danger, knowing their rights, learning negotiation skills, accepting themselves, their strengths, and setting appropriate boundaries. Open and non-judgmental communication is key to empowering teenage girls, says Angela Watkins, counsellor at Red Door.

Parents need to cover sensitive topics such as sex, alcohol consumption and dating in a way that children understand and can communicate.

They need to know that they won’t be judged and – if something does go wrong – what they have to say will be heard and accepted.

“You may not want to acknowledge that teens in Hong Kong are exposed to drugs and alcohol, for example, but it seems that many of them have access to these substances. To keep a teen safe, do not preach and hope for abstinence. Set time aside to explain to them the sensitivities of their developing brains, and help to work out a safety plan with them.

For example, discuss hypothetical situations such as, ‘If you were at a concert and you noticed that your friend had too much to drink, what would you do?’ Help them build the confidence to ask for assistance from a trusted adult if they find themselves in a challenging situation, so they look out for themselves and their friends,” Watkins advises.

Confessions of a Hong Kong underage drinker: vodka, jello shots, heavy make-up and a fake ID – after all, she’s only 14

Misperceptions such as “she didn’t fight back physically, so she was not sexually assaulted” or “the girl asked for it by the way she dressed” can sometimes lead victims to blame themselves and discourage them from seeking help, says Ng Hei-tung, community education manager at Mother’s Choice, a local charity that has supported pregnant teens affected by sexual abuse. Aimed at teens between 12 and 17, the group delivers a comprehensive sexuality education curriculum to schools and youth organisations, with an emphasis on busting such myths.

Reasons a victim may not disclose abuse include guilty feelings of bringing shame to the family, fear of retaliation from the perpetrator, or the belief that it is a one-off case and should not be exaggerated, says Kanice Ho Sze-kan, child protection adviser at Viva – Together for Children in Hong Kong. The group organises workshops for children and advocates for the establishment of proactive child safeguarding protocols at places such as schools, clubs and religious groups.

Lam, who says her brother was also abused by her uncle, believes that boys are more likely to hide the fact, largely because of societal and cultural conditioning.

My experience, as a survivor, is unique. In that sense, I’m alone. But as a mum, I no longer feel alone

“It’s naive to think boys are safe from sexual abuse. My uncle abused my older brother and perhaps his own son, too. But we’re from a traditional Asian family and they’re boys, which means they’re not taught to speak up about such matters. When my brother started wetting the bed at the age of 11, my parents called him a baby,” she says.

Sexual abuse is not as obvious as bruises and marks, but parents can be alert to noticeable changes in their children’s habits, emotions, sleeping, appetite and behaviour, says Donna Wong Chui-ling, acting director at local NGO Against Child Abuse.

“Pay attention to atypical sexual behaviour – when children do something that is clearly beyond their development stage (for example, a three-year old attempting to kiss an adult’s genitals) or that involve threats, force or aggression, or strong emotional actions such as anger and anxiety. If you are confused, get a trained social worker or therapist to help to determine the root cause of the behaviours,” Ng advises. A change in the child’s behaviour around certain individuals is also a giveaway.

Respond appropriately if a child does disclose abuse. Even with good intentions, reactive and poorly thought through responses can significantly affect a child’s well-being,” Ng warns. “Displaying denial, shock or disgust to a child, for example, may reinforce feelings of guilt and shame, making them shut down and complicating their recovery process.”

Under no circumstances should parents blame the victim, Watkins says. “I don’t want any child who has been abused to torture herself over what she could have or should have done to keep herself safe. Such thinking can trap victims of violence in a cycle of self-blame.”

Parents should try not to blame themselves, either, Lam says. “My parents aren’t to blame. We can’t protect our children from everything. The important thing is they took action. Unfortunately, my brother can’t say the same.”

In suspected cases of child abuse, parents can notify a familiar professional like a doctor or a teacher; or they can directly contact Against Child Abuse or the Social Welfare Department. Details of the informants and the victims will be kept confidential. Following home visits to assess the risk level, the nature of the abuse and the emotional state of family members, the victim and family members will be offered free support and counselling.

In emergency or criminal cases, it is necessary to involve the police. Appropriate measures will be taken to ensure the child’s ongoing safety. “Only through responding swiftly and appropriately can children start their path to recovery,” Wong says.