Chinese Americans on tours to Guangdong to seek out their roots, and their emotional journeys

For nearly 30 years a non-profit has been helping Chinese Americans discover their family history in southern China – visits that can stir up strong emotions, reinforce participants’ Chinese identity and lift a veil on forebears’ sacrifices

When Jason Zheng was growing up in San Francisco, he wasn’t proud of being Chinese.

“I always had a need to fit into white culture and wanted to shed the Chinese part. I thought Cantonese sounded harsh, and Chinatown stinky. I just wanted to fit in,” he recalls.

But around the year 2000, he attended a presentation in college by Hong Kong-born Ruthanne Lum McCunn, who is half Chinese, half Scottish. The author of Thousand Pieces of Gold (2015) and Wooden Fish Songs (2007) talked about how she was proud of her Chinese roots, and how much she loved Cantonese culture and language. Zheng sat in the audience dumbfounded.

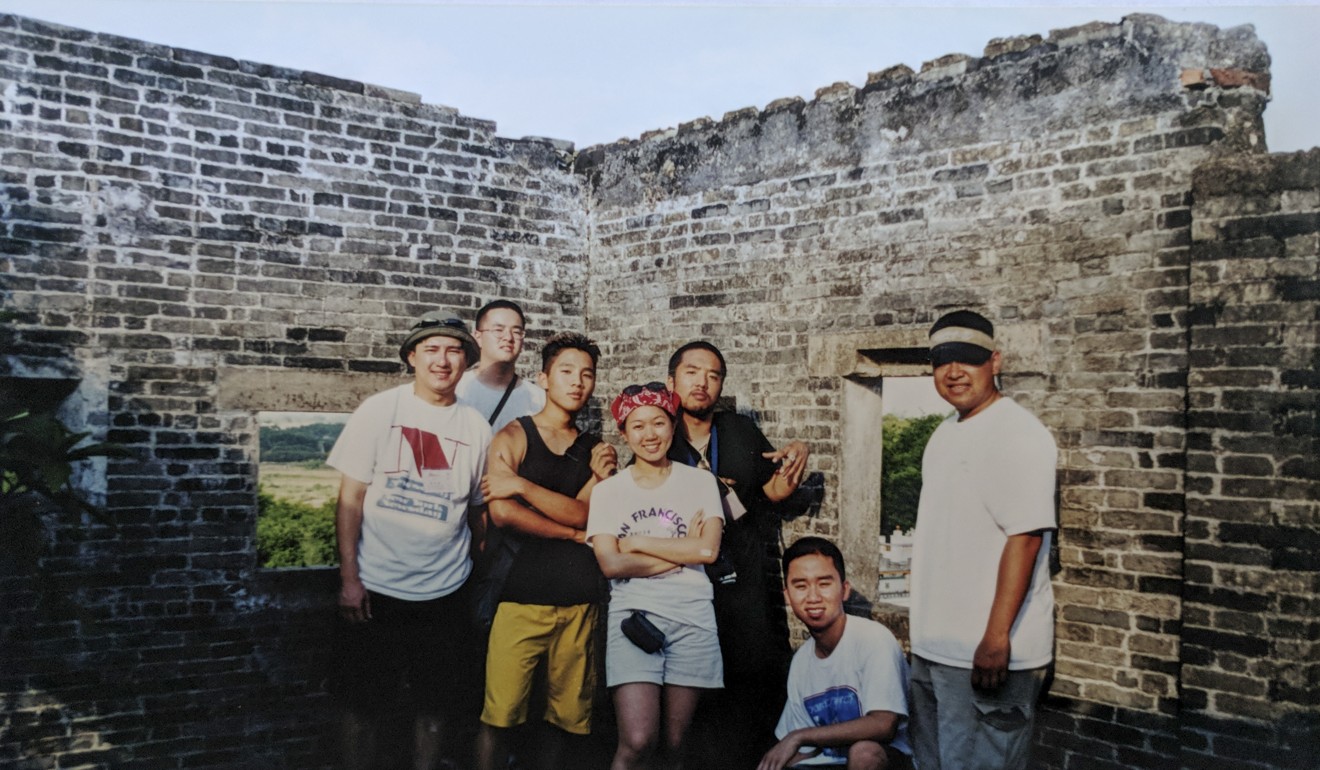

Founded in 1991 by Cheng and the late Chinese-American historian Him Mark Lai, the non-profit guides young people from 18 to 30 years old through three months of seminars before taking them on a two-week-long trip in July to Guangdong to visit their parents’ ancestral villages (most migrants to the United States in the 19th century were from this southern Chinese province adjoining Hong Kong).

How a Chinese-Jamaican’s family history quest led her to Hong Kong

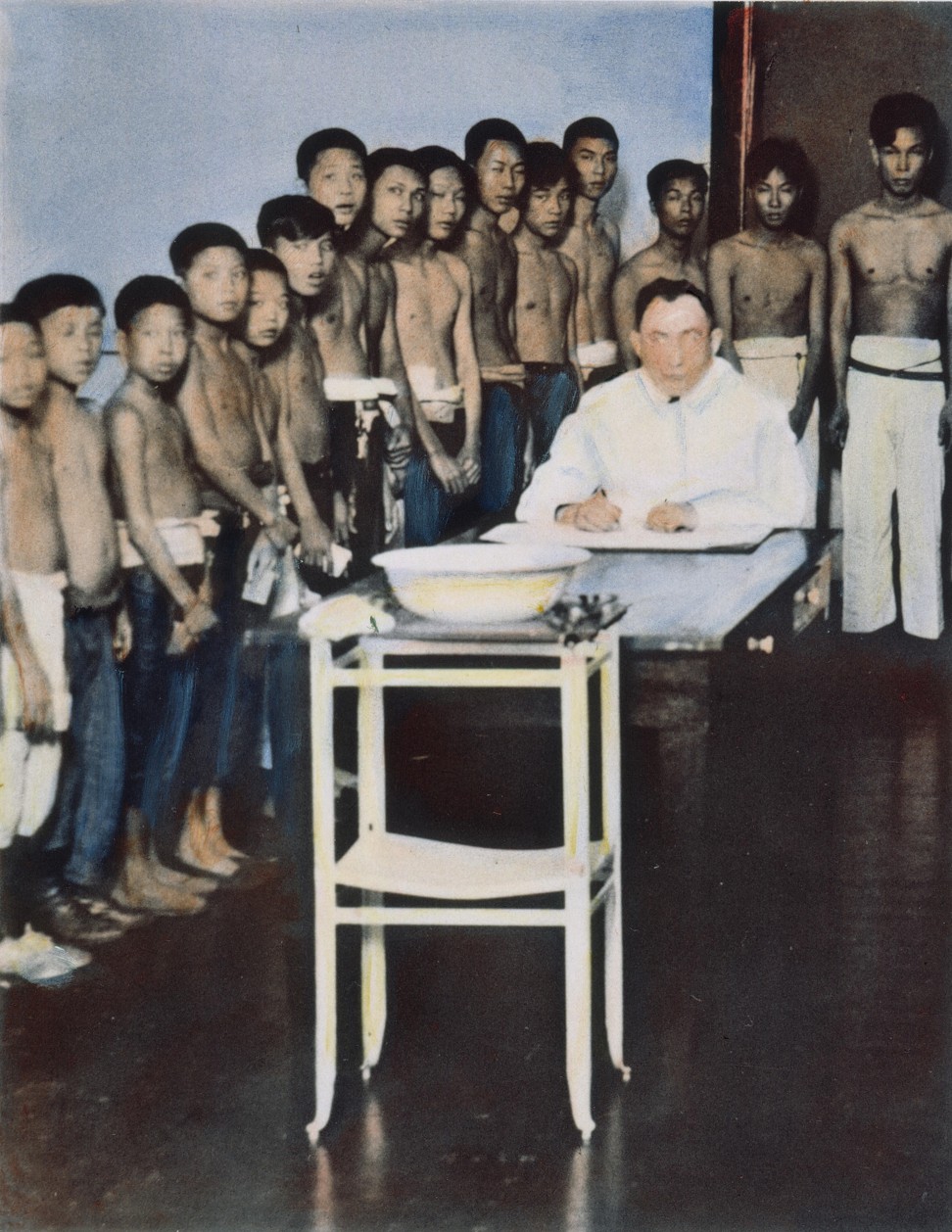

These young “rooters” must fill out their family tree with as much information as they can find, not only from their family but also through the US National Archives and Angel Island Immigration Station, where many Chinese immigrants first landed in San Francisco. They also learn about Chinese-American history and modern Chinese history, and get China travel tips.

While on the trip, the group is accompanied by officials from the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of Guangdong Province, who help rooters find the villages and relatives they are looking for. To date more than 300 people have been helped by Friends of Roots and many have stayed in touch with the organisation; some even ended up as board members.

For Zheng, 39, his 2004 trip was a struggle in which he tried to come to terms with his emotions about his relationship with his parents.

I felt, boy, if my family didn’t leave I could have been barefoot in split pants. I could have been a farmer

While his mother’s side of the family emigrated to San Francisco, his Cantonese-speaking father stayed behind in Guangzhou as a professor at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts because he could not find work except as a janitor.

The angst-filled Zheng didn’t get along with his Mandarin-speaking mother growing up, nor did he have a good relationship with his maternal aunts, uncles and grandparents. But he hoped to remedy the situation through the Roots programme by visiting his mother’s ancestral village.

“When we walked through, there were more dogs and old women than young men,” recalls Zheng. “Our village seemed to do well because ours had money sent back. We went to other rooters’ villages in Hoi Ping [a district near Jiangmen, a city in the Pearl River Delta] and the ones that were wealthy had more doors and locks, while the poor ones were very hospitable.”

A distant uncle showed Zheng around, pointing out in the two-storey family home where his grandmother slept and where his mother studied. “I placed myself in their shoes and it made me realise my mom studied hard so that she could get out and then have me, a spoiled brat. I was embarrassed by it,” he says now.

Zheng’s realisation of his relatives’ sacrifices is an epiphany Cheng, now 69, has seen numerous times during the more than 50 trips he has made to China in almost 30 years. It’s similar to how he felt back in 1988 on his first trip to China.

Cheng asked his brother-in-law to show him his paternal family village in Zhongshan, a city in the Pearl River Delta. “It was still backward,” he says. “We went to the school where my father attended and I sat in every chair to make sure I sat in the same chair as him.

“Being there, I understood life was rough and why people left. I felt, boy, if my family didn’t leave I could have been barefoot in split pants. I could have been a farmer.”

An educator for over 30 years and self-described “genealogy fanatic”, Cheng has traced his family roots to find he is the 26th generation of his village.

Shenzhen village plays host to Hakka descendants – including Jamaican/African Americans

Cheng’s seminal trip led him to co-found In Search of Roots to engage young Chinese Americans by bringing them back to China to experience what he did.

The results of such trips are nothing short of intense, with many rooters having visceral feelings about family issues that surface, and in many cases Cheng doesn’t even know about them until they are on the trip.

One example is Cheryl Tien, who had a strong emotional response when she stood in front of her ancestors’ altar almost three years ago.

She had a strained relationship with her Vietnamese-Chinese father, who was not around much when she was growing up, and when he was diagnosed with a recurrence of nasopharyngeal cancer, Tien was worried he might not live much longer.

“We had a complicated relationship – a lot of resentment had built up even though he put me on my career path. He was never around doing the Caucasian dad thing,” says Tien.

“Al [Cheng] knew this was hard on me and he instructed me to say prayers to speak to my ancestors. I told them, ‘We’re OK, we fight a lot. No matter what, we have to take care of each other. You’ll see dad soon. He’s done his best.’ I’m a science girl, but when I was there, I felt the warmth and aura of my ancestors.”

Tien’s father is still around, though his health is declining and he was pleased she went on the trip. But for her, standing in front of the family altar was a cathartic experience that let to acceptance.

“My last name means so much to me,” says Tien. “It doesn’t begin with my dad, but goes back generations. I don’t let things rile me up as much because I now see the grand scheme in life.”

Meanwhile Californian-born Korey Lee’s Roots experience enabled him to have a greater appreciation for what his mother’s side of the family went through when they arrived at Angel Island.

From Harlem to China: how an African-American tracked down her Chinese grandfather

“When we went there to do research, it was trippy to see the interview documentation of my relatives,” he says of the immigration procedure.

“It was heartbreaking to see how difficult it was for them to come into the country. Some people were sent back to China weeks or months later because they couldn’t answer such obscure questions as exactly how many steps from the front door to the living room.”

For Lee, 34, seeing his father’s village, Ma Mei Wu, an hour outside Taishan in southwest Guangdong, made him feel more blessed and privileged.

There was no running water, but a well in the village that had rice paddies and water buffaloes. There were squat toilets, and the furniture and linens were still in the house,” he says.

Lee saw pictures of his father, brothers and sister, and even pictures of himself and his family that they had sent.

I don’t let things rile me up as much because I now see the grand scheme in life

“I saw what life could have been if my grandfather hadn’t taken that risk to move to the US. I learned more about him, how he worked in the navy as a cook, then a laundromat and restaurants. But he was able to save up enough to buy a house and put my dad through college, and move his family over one by one,” he says.

Lee, who works in data analytics in Hong Kong, believes time is running out to visit ancestral villages because the history and information is not documented, let alone digitalised – it is dependent on personal recollections.

Nevertheless, visiting Ma Mei Wu has made him proud to be Chinese and American, and he says he has more confidence of his direction in life. His younger brother and sister went on subsequent trips.

Filmmaker Evan Jackson Leong, 38, felt a similar boost to his self-identity after going on the Roots trip over 20 years ago in 1997, which later influenced his work as a filmmaker.

The sixth generation Chinese American says the programme gave him a better perspective of who he is – that he’s not Chinese from China, but not totally American either.

“Roots helped me form what I’m about – what my voice is, about the Asian American experience – and make it relevant to the world.”

The Hongkongers who emigrated to Trinidad and their descendants who returned

He also says Cheng encouraged him to open his mind to different perspectives and follow his interest in filmmaking.

“Once you understand the techniques and methodology of filmmaking, then you need to know what you want to say, and I want to do things that I find interesting, which is about Asian Americans. For me it’s important. If I don’t do it, no one will.”

In 2013, Leong’s breakout film Linsanity followed the rise of Taiwanese American NBA basketball star Jeremy Lin, particularly when he was with the New York Knicks.

Leong’s current passion project is Snakehead, a fictional film about Chinese human smuggling in New York’s Chinatown that he aims to release this year.

He keeps in touch with Cheng, describing him as a mentor. “He knew that it was important to embrace the youth and we don’t just respect him because of his age. He’s been doing this for 28 years and he’s young at heart.”