Searching for her birth parents, Chinese girl adopted to the US 22 years ago just wants them to know she is safe and happy

In 1996, Carol Free adopted a girl, who she named Kathryn, and took her to California. This year Kathryn returned to China to seek her biological parents – but, for any number of reasons, they may not want to be found

On December 26, 1995, police on patrol at the railway station in the Chinese city of Nanchang made a heartbreaking discovery. Lying on the ground, wrapped in a blanket, was a baby girl. They took the infant to the Nanchang Welfare Home, a state orphanage, where carers named her Chen Zhantong – Zhan being Chinese for “station”. She was estimated to be just six days old.

Six months later, her life took a turn for the better when she was adopted by Carol Free, an audiologist from California.

Chinese girl adopted in US has miraculous reunion with birth parents

The Post met Free in a Nanchang hotel in 1996. Cuddling her beloved baby daughter, whom she named Kathryn, Free promised her the world.

“I have so much to offer her – good health, family, education. I have dogs, cats, a cute little house in Santa Cruz, and we’ll go to the beach on weekends,” Free, a single mother, said at the time.

In April this year, the Post reunited with mother and daughter in Nanchang, in Jiangxi province, southeast China. Free had brought Kathryn, now 22, back to her birthplace in an attempt to trace her biological parents.

Kathryn says she is keen to have a relationship with her birth family, even though she has a loving relationship with her adopted mother.

“I knew I was adopted all along. I didn’t feel abandoned or incomplete because I was always filled with love. There was never a time when I got home from school and my mom would not be available. She’s my best friend,” she says.

China passed a law allowing international adoption of Chinese orphans in 1992. At that time Joshua and Lily Zhong, a couple from China who were studying in the US, founded Chinese Children Adoption International (CCAI). The organisation arranged Free’s adoption of Kathryn and that of hundreds more in the years to come, as a generation of abandoned baby girls – victims of poverty and a one-child policy – were adopted by American families.

According to the US Department of State, Americans have adopted more children from China than any other country, amounting to over 80,000 children between 1999 and 2017.

Free says that while Kathryn is an American, she also made sure she immersed her daughter in Chinese culture.

Kathryn describes herself as “technically Chinese” but really an American who loves pizza, burritos, tacos and sourdough.

“As a kid I felt I should know Chinese culture. We never missed celebrating Chinese New Year – and July 4 [US Independence Day] – with our Chinese community, and my mom would be the only Caucasian there. She also enrolled me in a Chinese school in San Jose, where I learned to count and sing Chinese songs,” she says.

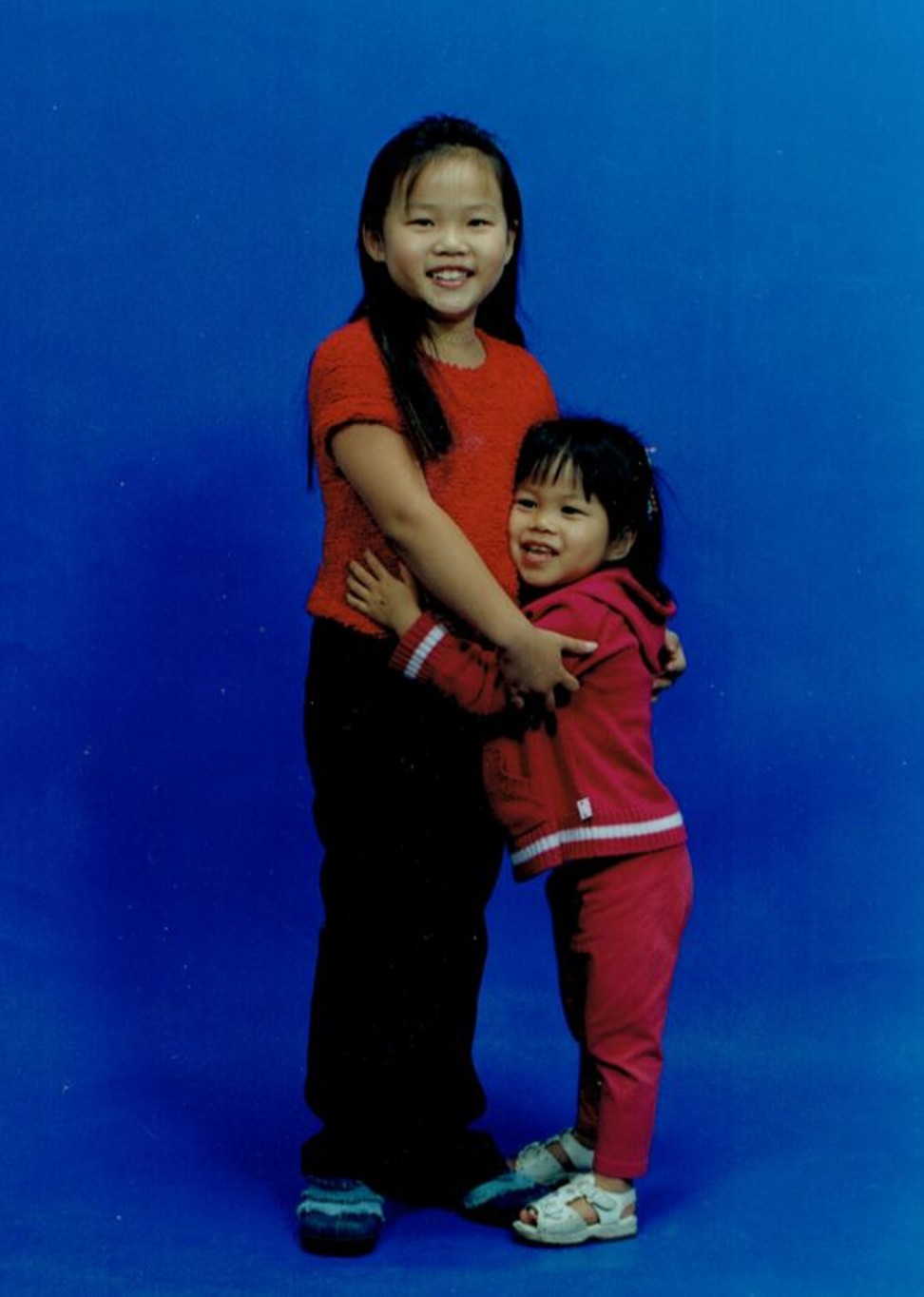

Kathryn has made the trip back to China on a number of occasions over the years, the first time in 2000 when they visited to collect a little sister, Connie, for her. The family returned again in 2011 and visited eight cities as part of a heritage tour hosted annually by the Chinese government for returning adoptees.

Their last stop was Nanchang and a visit to the orphanage, which had hung a huge red banner across the entrance that read: “Welcome Chen Zhan Tong Back Home”.

“I wasn’t emotionally connected to the orphanage, but when I saw the banner I realised I spent the first six months of my life there and was well taken care of,” Kathryn says. “I was in tears.”

Two years after that trip, aged 17, Kathryn worked as a volunteer at orphanages in Henan province with 30 other adoptees as part of a programme CCAI organises every year for the girls who were lucky enough to be adopted by loving families abroad.

“I saw babies who were abandoned because they’re cross-eyed or have a cleft palate, which can be easily fixed in the US,” Kathryn says.

The social stigma is enormous. [The parents who gave up their children] will be accused of being heartless and irresponsible, especially if the child was sick

The experience struck a chord with Kathryn. When she returned to the US, she began taking physiology and anatomy classes at school, paving the way for nursing studies at Boston College. After graduating and earning her nursing licence last year, Kathryn is now pursuing a master’s degree to become a nurse practitioner, which will enable her to provide patients with a higher level of care.

“I want to be a travelling nurse and go where I’m needed – China, South America, India, Africa, all over the world,” she says.

On their latest trip to Nanchang this year, the Frees joined two other American mothers, Faith Winstead and Erin Valentino, on the mission to track down the birth families of adopted children.

In January the pair launched the Nanchang Project, which provides a social media platform where information about adopted Jiangxi children can be posted, such as birth dates, finding spots and physical characteristics. The hope is that it will be seen by biological parents who wish to reunite with their children.

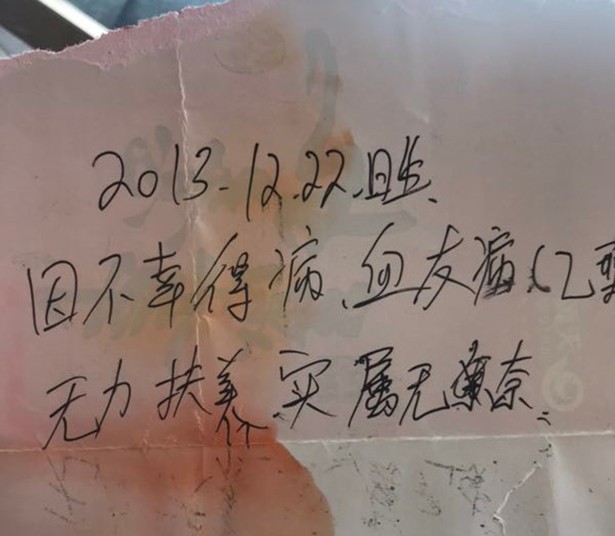

One profile is that of Hong Yumeng, a baby girl discovered in Nanchang’s August One Square in 2013 and adopted by the Valentinos in 2016.

Winstead adopted two sons from China – Jiancheng from Nanchang, who has haemophilia, and Renda from Changzhou, Jiangsu province, in 2016 and 2017 respectively.

“Our kids have lost so much – their birth families, language and culture,” Winstead says. “We want to fill in the gaps and maintain their relations with China.”

The Nanchang Project gained a lot of publicity via social and traditional media in China, and a number of volunteers came forward to offer their services as guides and translators. One volunteer is Lian Yichun, a police officer from Hubei province who has reunited dozens of abandoned and abducted youngsters with their families. He says it is never easy for parents to give up their children.

“It’s not that the parents are cruel … But when you’re starving, how can you feed another mouth or pay doctor’s fees? So they leave their child in a crowded station, pier or public square to be found,” he says.

Kathryn is convinced her birth family loved her very much. “In desperate circumstances, they needed to do what they thought was best for me. They left me at a train station. I was found and adopted. Everything worked out for us better than ever expected.”

Lian believes some birth parents who recognise their child in internet posts will hesitate to come forward.

“The social stigma is enormous. They’ll be accused of being heartless and irresponsible, especially if the child was sick. They’ll have no face or standing among friends and relatives. Some may risk losing their job,” he says.

Meet the American journalist who adopted abandoned Chinese babies

Another community volunteer, Zhu Yanzhi, says China’s Public Security Bureau has a DNA database that could be used to help youngsters find their biological parents, but also acknowledges that not everyone wants to be reunited.

“While parents who abandoned girls have later submitted DNA samples to the police to find their daughters, parents who have given up disabled children are most reluctant to come forward fearing they’ll be asked to pay back all the medical bills,” Zhu says.

Kathryn has submitted a hair sample to a charity in Guangzhou that offers a DNA matching service for birth families.

They must have been burdened by so much guilt all these years. I just want them to know that their child is safe and happy

While child abandonment is a complicated issue in China, Winstead and Valentino believe they’re bringing a message of hope, love and reconciliation that transcends political and cultural boundaries.

“Our kids are growing up happily in the US. They never lack love from us. But we don’t want to just stop there,” Valentino says. “We want to find the missing link to their past. We want to let them know who they are and never feel shamed because they’re adopted. We want our kids to be proud that they are Americans and Chinese at the same time.”

During the annual heritage and orphanage trips, the Chinese government reminds the adoptees not only of their roots in China, but to be thankful for the love and care given by their American families.

Lian says the government should also seek ways to remove the social stigma attached to adoption and abandonment, and encourage birth family reunions.

Kathryn says finding her birth family would enrich her life. “I’d listen to their story and we’d share with each other about our lives,” she says. “They must have been burdened by so much guilt all these years. I just want them to know that their child is safe, happy, healthy and thriving.”