Free school supported by Hong Kong professionals proves a big success in Shanxi

A free school in Shanxi supported by Hongkongers tops the province's education charts, saysAlan Wong

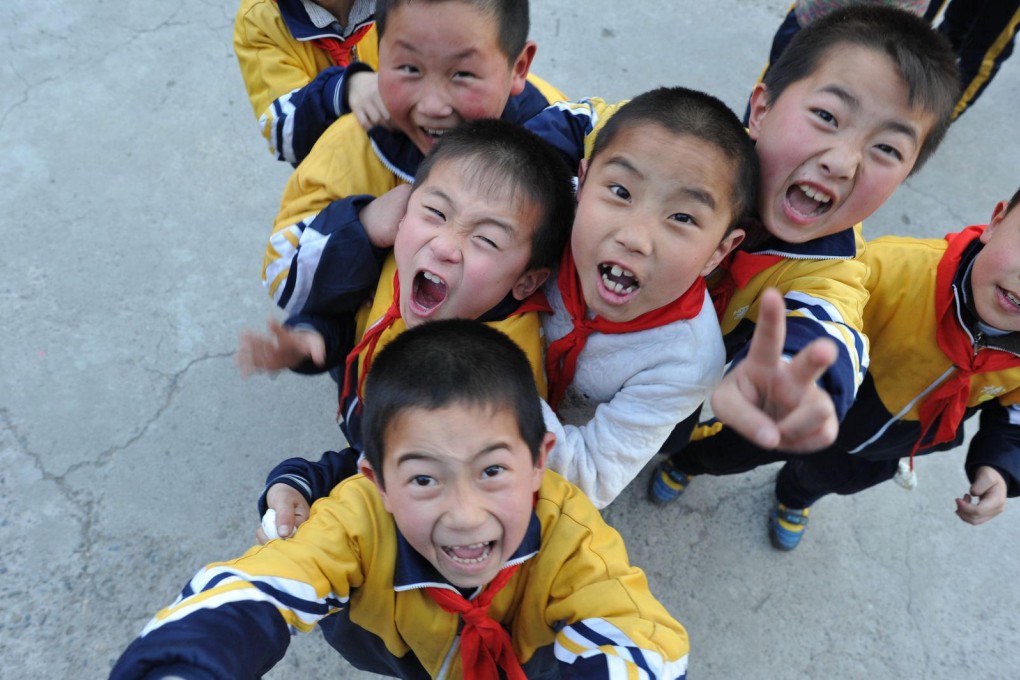

Hong Kong entrepreneur Tam Man-chi, a keen photographer, never had such a rapturous reception as when he visited Fengcun village in Shanxi province. He was there at Easter to view the Bo Ai School, a free boarding facility for primary pupils he helps support. Tam says he felt like a rock star.

"Many of the children had not been photographed before. So I was ambushed every time I raised my camera," he says. "I saw so many happy faces. In Hong Kong, children have much more stressful lives, despite their higher living standards."

A dozen years ago, there was little to distinguish Fengcun, a community of fewer than 1,000 people in the mountainous region of Qingyuan county. It was dirt poor, with a number of villagers living in spartan homes carved out of the loess. Few of the 180 families in the village had access to a water supply. Children walked for several hours to reach school.

Bo Ai School has put Fengcun on the map. Founded about six years ago by an American-Chinese couple, Christine Chan Hoi-chu and her ophthalmologist husband Dr Patrick Chan, the school has won provincial government endorsement as a model facility.

For a school with such a brief history, Bo Ai has achieved impressive results. It produced half of Shanxi's top 10 primary students in 2010, and in a provincial English test, was ranked top among nearly 100 schools. Now the school attracts hundreds of visitors, including other institutions in the region eager to replicate its success.

Christine Chan, 61, decided to establish the school after a chance meeting with a doctor from Shanxi prompted her to make an eye-opening visit to Fengcun in 1999.