Someone recently asked me an interesting question - do schools grade on the bell curve? When I replied in the negative, I was asked why not since several well-known standardised tests allocate marks or grades this way.

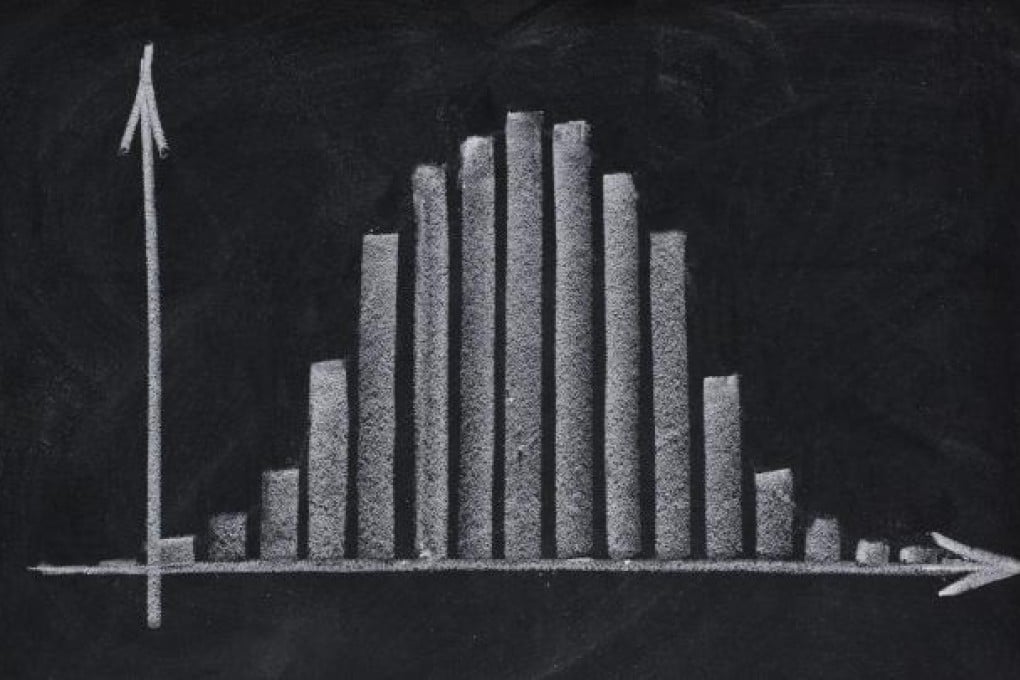

Commonly referred to as a normal distribution (or a Gaussian distribution, after German mathematician and physicist Carl Friedrich Gauss), the curve graphically represents statistical events. The peak of the curve or the top of the bell, shows the most probable event or, in education, the mean.

In university and some standardised tests, grading on a curve is a statistical method of assigning grades designed to yield a predetermined distribution among a group of students.

Because this involves rating students' performances in relation to that of their classmates, curve grading has also come to refer to any grading method that uses comparisons of students' performances, although it may not actually apply a bell-shaped frequency distribution.

Grading on a curve came into existence because of the subjectivity teachers show in marking student work. Pioneering research by Daniel Starch and Edward Charles Elliott in 1912 showed that English teachers assigned widely varied percentages to two identical papers from students. Some teachers focused on elements of grammar, style and neatness; others considered only how well the message of the paper was communicated. A subsequent study on geometry papers by the same researchers confirmed this subjectivity. Some teachers deducted marks only for inaccurate calculations and wrong answers while others deducted marks for neatness and spelling as well.

Evidence of such variation in grading led to a move away from percentage scores to scales that had fewer and larger categories.

Standardised tests including the International Baccalaureate exams enable us to compare the performance of students with each other in a relatively efficient way. But how much can such tests tell us about what students actually know?