Opinion | Learning Curve: the tyranny of predicted grades

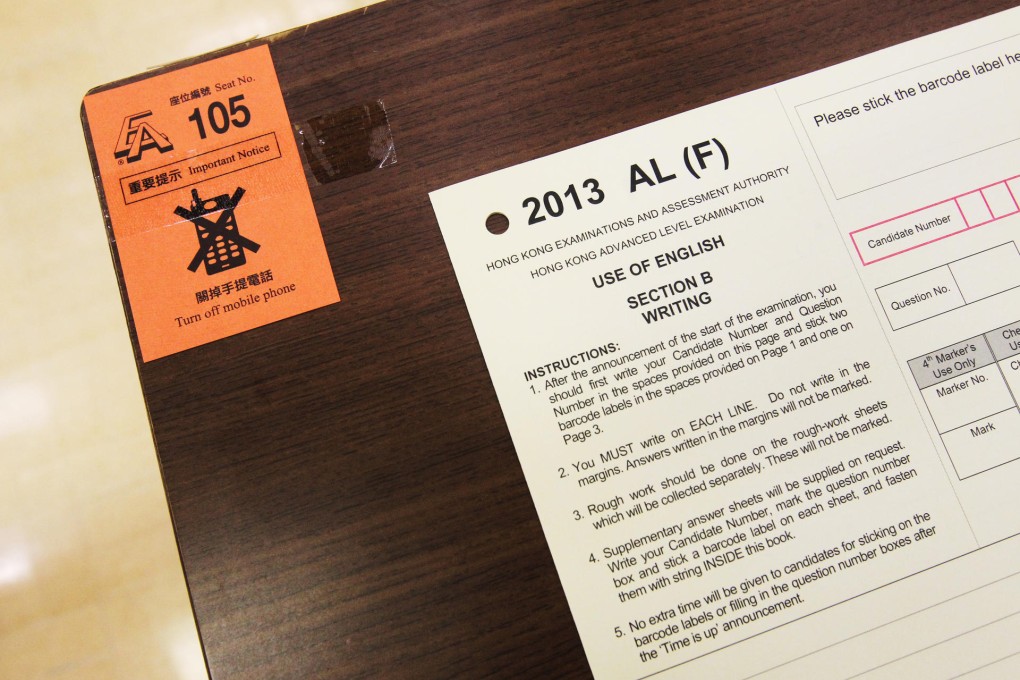

As students sit their exams for the International Baccalaureate (IB) and International General Certificate for Secondary Education (IGCSE), I am reminded of the hundreds of predicted grades I have given out in my teaching career.

As students sit their exams for the International Baccalaureate (IB) and International General Certificate for Secondary Education (IGCSE), I am reminded of the hundreds of predicted grades I have given out in my teaching career.

How accurate have I been and how have my predictions affected my students’ admissions to universities?

Researchers Nick Everett and Joanna Papageorgiou, from Britain, investigated the accuracy of predicted GCE A-level grades as part of the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service admissions process. They report that 51.7 per cent of predictions were accurate, 41.7 per cent by at least one grade. Only 6.6 per cent of all predicted grades were under-predicted.

“A” grades were most accurately forecast (63.8 per cent accuracy) compared to 39.4 per cent of “C” grades.

What other factors influenced the accuracy of my predictions? Everett and Papageorgiou report that gender plays a part in predicting grades. Female applicants were more likely to achieve their predicted grades and were more likely to be accurately predicted than male applicants.

And teaching to a higher socio-economic group at an independent school has apparently made my predictions more accurate.

As an educator, it is much easier to predict a seven for IB and an A* for IGCSE based on school assessments when students marks exceed the mark boundary for those grades.