England can learn from Scotland's more fun, well-rounded education

Compared to exam-obsessed England, Scotland's officials have favoured a curriculum that looks beyond the grades, writes D.D. Guttenplan

In the leafy subdivision of East Dunbartonshire, outside Glasgow, the hallways of Bishopbriggs Academy were buzzing from a production of the musical Bugsy Malone the night before.

Inside Kathryn Macleod's English class, 12-year-olds were watching a clip from the film version of Louis Sachar's novel Holes, paying close attention to the actress Patricia Arquette. After making notes on Arquette's character and comparing her performance with the novel, the students each composed a director's note for the actress.

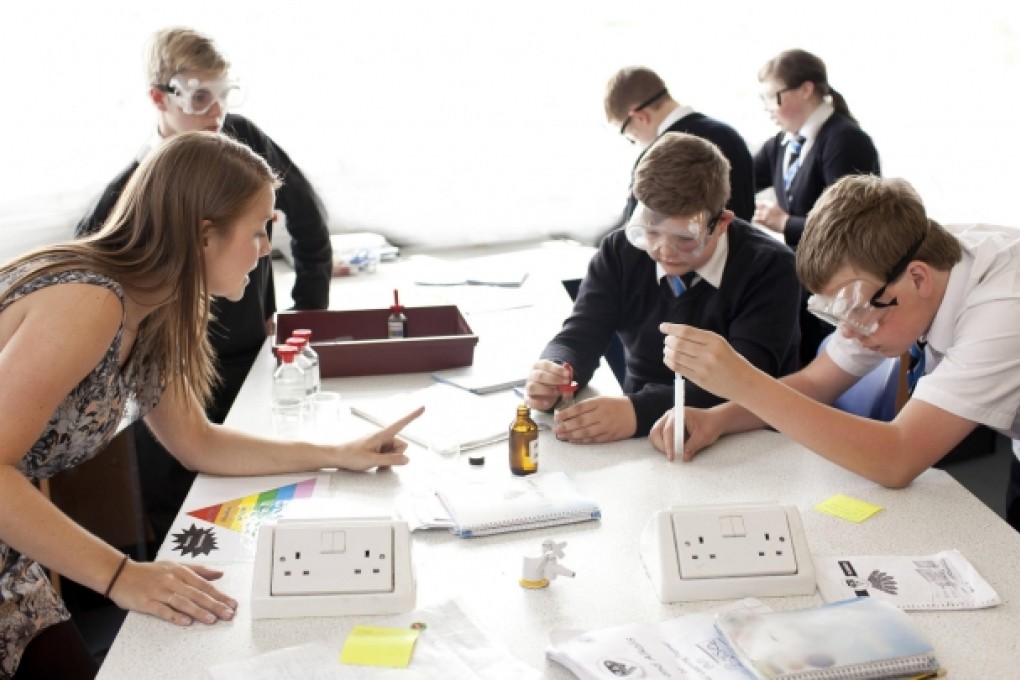

Down the hall, Lauren Neilson's science students were boiling red cabbage over Bunsen burners as part of a lesson about measuring acidity.

In recent years, schools in Britain, like those in the United States, have struggled under an increasing burden of testing and assessment designed to improve quality and to enforce some version of national standards. Critics of such changes have pointed to the success of Finland, which, despite imposing far fewer tests on its students, has consistently performed well in exams of the Programme for International Student Assessment.

Perhaps English parents and policymakers would do better to turn their attention slightly nearer. Education in Scotland has long been run differently from the rest of Britain. While schools in England encouraged students to specialise, Scottish schools traditionally aimed for a greater breadth of knowledge.